Strengthening Australia’s assisted voluntary return migration program

This working paper examines assisted voluntary return programs in other countries and argues a customised approach to the Australian AVR program design can increase its performance.

Abstract

Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) programs facilitate travel for migrants who want to return home but require financial assistance to do so. In Australia, the AVR program is primarily employed to facilitate return for migrants who have no ongoing legal avenue to stay, but is generally available to any migrant who needs assistance to return home. Through small policy changes, Australia is able to learn from AVR programs in like-minded countries and achieve a greater number of returns.

Introduction

Return migration is an emerging policy challenge for the Australian Government. It is a challenge because without good return migration, Australia will be unable to maintain the integrity of its broader migration program.

Part of the challenge is its breadth; return migration covers multiple areas in the Australian immigration program, including forced returns, voluntary returns, and migrants self-funding their return home. Notwithstanding the success of Operation Sovereign Borders ‘stopping the boats’, the Australian immigration system is still facing the largest caseload of asylum seekers in its history. A large number of them are currently required, under law, to leave Australia but simply do not want to go. This means that the Australian Government will need to enforce return arrangements for the majority of these people. Without good forward-thinking, Australian policymakers will be unable to develop a program capable of accommodating current and emerging return caseloads.

A balanced approach to this topic acknowledges it is difficult to achieve the right settings for a return migration program. ‘Return’, be it voluntary or involuntary, is a predictably contentious and thorny issue with the potential to continually divide public opinion. Policy solutions on this topic are subject to public opinion tests, and a different pressure is applied compared to the rights and wrongs of administrative and legal tests. For example, Australia’s decision to perform a forced return can pass legal or administrative tests but can still fail in the court of public opinion.

Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) programs have a mixed reputation. The program is, on the one hand, seen as good because it assists migrants to return home. On the other hand, the program is just as quickly considered bad because it pays migrants to go home. Nevertheless, AVR programs play an important role in return migration and the right policy settings are crucial to achieve the highest number of returns. In Australia, when a migrant has no ongoing legal avenue to stay, the Australian Government encourages this person to self-fund their departure. Where there is no ability to self-fund, the government is able to sponsor the return journey via the AVR program.

The aim of this working paper is to identify how Australia’s current AVR program can be strengthened, including via a consideration of similar programs around the world. Compared to other countries, Australia’s return migration program is young and there are significant opportunities to learn from other nations that have experienced similar challenges. While Australia can manage some of these challenges with existing policies, others will require the development of more customised programs.

AVR programs

All AVR programs are designed to assist migrants to return home. The kind of assistance can vary from case to case as per the national policy of a particular host country. Most AVR programs have common items of assistance, and these are administered via a chosen service provider. This assistance usually involves payment for travel-essential items including door-to-door travel assistance to return home and payment for any necessary travel documents (e.g. passport/emergency passport). Small cash allowances are occasionally available for those returnees who need money for incidental expenses, such as food and phone calls. How the program works in practice, on the surface, is fairly straightforward. Once a migrant has been introduced to a service provider, a determination is made about what kind of assistance is required to facilitate departure.

It is important to note that not everybody who requests assistance from an AVR program is eligible to receive it. Although administered by a service provider, the host government still maintains control over who is able to participate and may decide to exclude certain migrant groups from eligibility.

The Australian AVR program

Australia’s AVR program has been in existence, in one shape or form, since 2002. Originally established to accommodate the requests of failed asylum seekers from Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan, the program offered different types of assistance to facilitate return, ranging from travel assistance to in-country housing assistance.

The present-day program is able to facilitate return for all migrants, but particularly for those who hold a visa that does not allow permanent ongoing stay in Australia. This means the program is able to accommodate requests for assistance from asylum seekers, failed asylum seekers, visa overstayers, and those without a valid visa. The current program offers travel assistance and also provides for extended in‑country assistance, known as reintegration assistance, for some returning nationals. The program has always been delivered on behalf of the Australian Government by a single service provider, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and is currently managed by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP).

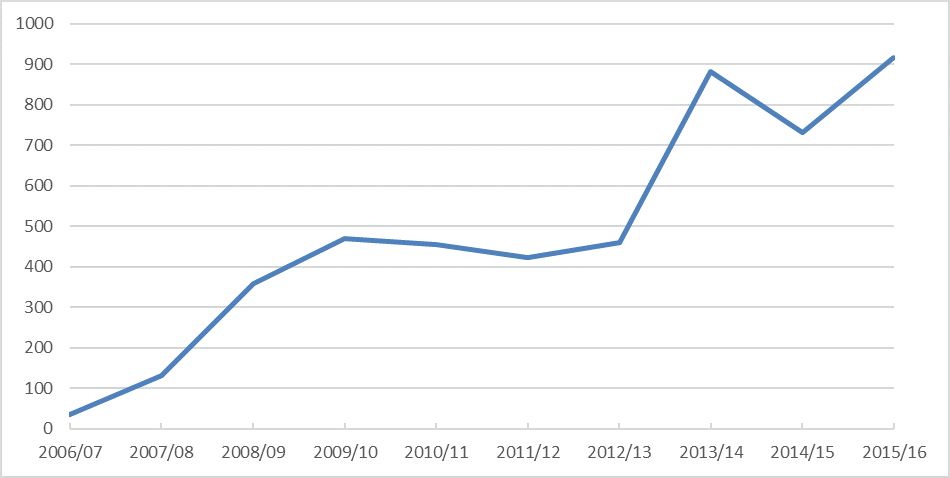

Figure 1: IOM-assisted returns from Australia, 2006/07–2015/16

Source: International Organization for Migration

Challenges

The relatively young age of the Australian program is both an advantage and a disadvantage. The original expectations for the program were conservative, as it was designed to only service a discrete group of migrants. Since 2002, the demands of the program have changed and it is now required to service a broader population. Functionally, though, the program has not adapted to those changes, meaning there have been times when it has been unable to support the objectives of government. However, with small enhancements, the program can achieve a higher number of returns.

Over the life of the program, there have been some major changes in the Australian immigration population that have not been accurately reflected in AVR program settings. Most notably, caseloads have changed. Australia received a large number of undocumented asylum seekers in 2012/13 and the majority of this group is now residing in the Australian community awaiting a visa decision. The sheer size of this group has made it challenging to manage. Most people in this group want to stay in Australia, irrespective of whether a legal process permits them to stay.

Failed asylum seeker caseloads the world over contain people who cannot stay in a host country but do not want to go home. In the majority of cases, host governments are expecting AVR programs to facilitate departure for these people. This is visible in the Australian program where, in the absence of the ability to carry out forced returns, a large expectation is placed on the AVR program to produce results.

The reality is an AVR program is not designed to produce or promote returns, and is often unable, on its own, to generate and sustain departures. The involvement of a third-party service provider is one way of introducing another voice to discussions about returns. However, service providers such as IOM are not necessarily any more effective when it comes to informing a decision to return. Moreover, the Australian AVR program depends exclusively on one service provider to facilitate voluntary returns, and this is problematic. The IOM AVR program is good, but it is designed to function in a standardised way and Australia must take more of the lead role in adapting the program to its specific immigration challenges.

A brief examination of non-asylum seekers in Australia provides a good example of how the Australian AVR program can respond to current Australian Government migration management objectives. Non‑asylum seekers are a growing part of the Australian AVR caseload and are the easiest to assist through the AVR program. Identity checks are easier because the original border crossing was lawful, which makes for swifter acquisition of necessary travel documents, if required. However, non-asylum seekers are less likely to be introduced to the Australian AVR program, mainly because they are perceived to be able to self-fund their departure.

This is one example of how perceptions of an AVR program can impact on its effectiveness. It is not to say that all migrants who request access to return assistance should receive it but, for government, the counterargument does not make much sense. It seems counterproductive for migrants who are willing to depart, and are unable to afford an airfare, to be asked to pay for their own way home. AVR programs have the potential to finalise departure in a very short time frame, sometimes the same or next day. Even if there is no appetite for introducing more people to the AVR program, there must be a better way of producing departures sooner, rather than demanding people depart and waiting for it to happen.

Successfully incorporating AVR programs into broader migration management is part of the policy challenge. Although these programs operate in a variety of countries and perform a variety of functions, the primary intention remains the same: assisting people to travel from a host country to a home country. AVR programs do have their limits, though, and a degree of flexibility needs to be built into policy and program design to best fit a particular immigration setting. A common misconception is because the program, in its crudest form, pays migrants to go home, it is simply a matter of finding the right price. This is largely an overestimation of the capability of the program, and relies on simple logic; where returns of any description need to be facilitated, the AVR program is often seen as an attractive solution. This last point is partially true but cannot give rise to overdependence on an AVR program to produce the majority of departures. There has to be some cooperation between voluntary and involuntary functions of a returns program to provide the best possible settings for an AVR program to do its work.

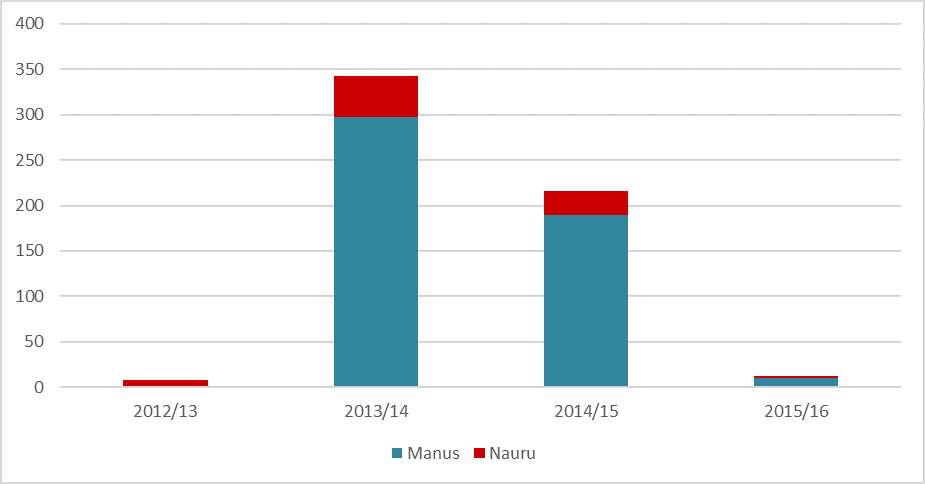

The Australian AVR program covers voluntary returns from regional processing centres (RPCs), which have been in decline since September 2014. At that time, the announced reintroduction of temporary protection visas in Australia appeared to be a major catalyst for decline, but there were other factors that steadily eroded the willingness to return, such as the perception of policy change and the commencement of refugee status determination assessments. Efforts over the same period to reinvigorate return numbers were also unsuccessful, with the announcement of higher cash returns allowances in April 2016 producing a small number of departures. These factors suggest two main points; that money is not the primary reason why people would choose to return home from RPCs; and the Australian AVR program has facilitated departure for all those who want to go. Also, RPCs are perceived as a temporary solution, and this uncertainty has affected momentum for voluntary return.

AVR programs have a limited capacity to significantly reduce irregular migrant populations, especially when there is an expectation that the program will produce large numbers of returns on its own. AVR is a small, niche function that has strengths and weaknesses, which may go a way to explaining why it is unable to consistently return the populations in RPCs. This suggests that AVR programs have a finite ability to produce returns, and those who remain are unable and unsuitable to be moved voluntarily. This is where it is necessary to complement AVR programs with other policies to ensure it does not stand alone. There is, for example, a strong relationship between voluntary and involuntary return programs, where consistent subscription to a voluntary return program relies on a visible, demonstrable involuntary return function. Without it, there is no reason for a migrant to initiate return. Targeted engagement can also add value to the program, by understanding the circumstances and the opportunities available to a person upon return, rather than focusing exclusively on paying that person to go home.

Threats

Returns policy has its threats as well as challenges. Two major threats are of particular relevance to the Australian returns program: ‘pay-to-go’ policy, and what constitutes ‘voluntary’ in the context of voluntary return.

The emergence of ‘pay-to-go’ policy, where large cash amounts are offered in exchange for an agreement to depart, complicates the individual parts of an AVR program, namely assistance to voluntarily return. This style of policy also challenges how a person can arrive at the decision to return. Some host governments place little emphasis on distancing a decision to return from a decision to accept an amount of money to return. While the result may be the same, the nuancing is necessary under a program called Assisted Voluntary Return. Returns facilitated via an AVR program should be free of coercion and based on an informed decision, and that includes overt financial incentives.[1] That is not to say that people cannot be paid, in a broad sense, to go home; they just cannot be part of a program professing to facilitate voluntary return.

There are fundamental problems associated with paying some migrants to leave a host country. For example, those assessed as refugees will face a dilemma about returning to an undesirable location versus returning with a large cash payment, and this does not contribute meaningfully to the global migration environment. The ‘pay-to-go’ style program is usually designed for easy-to-depart caseloads that are either travel-ready, or willing to acquire a travel document, not to legitimise or manufacture a decision to return.

Regardless, there is a place for pay-to-go policy, as long as it is used judiciously. Assistance paid by host governments to returnees is usually paid as cash, as a lump sum, or as instalments. This assistance is intended to facilitate reintegration activities on return; however, once paid, it is almost impossible to trace, even where it is administered by a service provider. This may not be an entirely appropriate program setting when paying people to go home to particular parts of the world. Some host countries are aware of the risks and are favouring government-to-government agreements to produce returns, rather than negotiating the terms of a return with an individual.[2]

Paying cash allowances to produce departure outcomes may increase departure in the short-run but, overall, does not produce sustained departure results. The Australian AVR program has attempted to have pay-to-go principles increase departures from RPCs. It is a novel way of temporarily increasing interest in returns allowances, but does not provide sustained departure results. On the other hand, pay-to-go programs are easy for host governments to administer, providing there is a population willing to engage with the program and any money paid to returnees can be administered quickly and securely.

There is an opportunity for returns policy to play a larger role in Australia’s migration management plan. There is also an opportunity for a reality check and for future returns policy to be better connected to Australia’s objectives for return migration. One priority is having clear objectives and custom-built returns policy for Australian immigration challenges. This will provide policy with greater capability and flexibility to move with the changing priorities of government, rather than relying on generic returns policy and program settings. It is a simple plan, with policy founded on good information then specifically applied to Australia’s domestic and international agendas for return. This allows government objectives for return to be clearly visible in policy.

Figure 2: IOM-assisted departures from RPCs, 2012/13 – 2015/16

Source: International Organization for Migration

AVR programs from other parts of the world

When it comes to strengthening its returns policy, Australia can look to AVR programs in other parts of the world. There are many adaptable solutions currently operational in countries that have, or have had, migration challenges similar to Australia including the United Kingdom, Canada, Belgium, and Norway.

United Kingdom

The past 12 months have seen significant changes to the voluntary return program in the United Kingdom. In 2015, the UK Home Office changed the service delivery arrangements for its AVR program, bringing the service that was formerly delivered by an external service provider in-house.[3] This was a major organisational shift, and the Home Office had to create internal structures to perform the business that was originally outsourced.

The change produced significant benefits, most of which are related to speed and control, and is a good example of a customised approach to returns program management. The new program provides greater speed to departure, and allows the Home Office to control cases from start to finish. Prior to the change, departure cases would be managed either by a service provider or by the Home Office, which did not provide the best continuity. Case management was prone to stalling at handover points, and this disrupted some of the momentum for departure messaging and planning.

One of the other strengths of the UK AVR program is the favourable legislative settings for the broader visa assessment process. These provide an effective way for identifying cases for progression to voluntary or involuntary departure.[4] While it is acknowledged that legislative change can take time, targeted review of policy related to visa processing, judicial and administrative appeals, including ministerial intervention, can occur in the interim, and any enhancements in these areas will be beneficial for Australia’s AVR program.

Canada

In 2012, the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) piloted an AVR program to see if it could effectively complement its forced return work. The aim of the program was to increase departures for failed asylum seekers who were unable to stay in Canada. Between 2012 and 2015, approximately 3700 migrants departed under the AVR pilot program from a targeted caseload of 6800.[5] Surprisingly, this result was assessed as unsuccessful and the program was discontinued in late 2015. The CBSA still facilitates voluntary return but not as part of an official AVR program. All departures are considered to be removals and are facilitated under law.

Although Canada’s experience with an AVR program was short, there is one feature of its program that is relevant to Australia. CBSA wanted to accommodate a defined group of migrants in its pilot AVR program, namely a group with no ongoing legal right to stay in Canada. There are migrants in Australia in the same circumstances, and some of the features of the Canadian program can be applied.

The CBSA halved the size of this caseload by increasing the activity and visibility of its enforcement teams, thereby creating greater pressure to depart. This approach is currently being pursued for small parts of the Australian immigration caseload, but could be broadened to include more migrants in different circumstances. For example, for migrants who choose to overstay their visa, the increased presence of enforcement teams may play out the same way it did in Canada and increase the number of departures.

Additionally, the CBSA broadened the eligibility criteria for its AVR program. In particular, a migrant’s willingness to depart trumps other factors, such as visa compliance and behavioural history, that would ordinarily mean a person is ineligible for AVR assistance. Australian AVR program settings can be modified in the same way and would likely lead to increased returns. For example, broadening eligibility would allow the Australian Government to consider new target groups for AVR assistance, such as migrants who have committed minor crimes.

Belgium

The Belgian returns program is purposely designed to achieve departures in a short time frame. Once an asylum seeker has been assessed as not being owed protection, the asylum seeker has a short time frame to depart, after which forced return procedures apply. Another feature is that both voluntary and involuntary return processes are legislated in Belgium, and the law prescribes time periods for compliance with departure orders.[6]

One of the advantages of the Belgian system is it provides a clear process for government to control, from visa decision to departure. This is different from the Australian system’s focus on voluntary compliance, which encourages migrants to resolve their own immigration status, including making independent arrangements to depart. The Belgian system clearly defines when the opportunity to voluntarily comply has been exhausted and, in the context of voluntary return, when the opportunity to voluntarily depart no longer exists. If the same system were applied in Australia, this would be a crucial signal for migrants who are required to depart. It would say, if you choose to remain in Australia beyond a certain point, you will be liable for forced return. There is an opportunity for the Australian program to be clearer with its definition of voluntary compliance, either through policy settings or legislation.

The Belgian system also separates voluntary and involuntary return functions into two separate government agencies. The involuntary return function is managed by the equivalent of the DIBP, and the voluntary function is managed by the equivalent of the Department of Social Services.[7] This separation permits more community engagement away from the gaze of immigration enforcement teams. By comparison, in Australia both voluntary and involuntary functions are managed by the same government agency, the DIBP. The ever-present challenge for the Australian voluntary returns program is being inappropriately conflated with the involuntary return program. Although the two functions are connected, there is a policy strength associated with preserving a distance between the two, allowing for one to operate without the undue influence of the other.

It is also noteworthy that voluntary return allowances and reintegration assistance have remained unchanged in Belgium since 1984, with the amount staying at the equivalent of €2400 per adult, approximately A$3500. Not every voluntary return from Belgium receives €2400; it is only available to certain groups in specific circumstances.[8] There is a similar structure in the Australian program, with reintegration assistance only available to certain returning migrant groups. This part of the Australian program is about 25 years younger than its Belgian cousin, and the assistance allowance has hovered at around the same amount since it started (approximately A$5200 per adult). The difference in the age of the two programs provides insight into the immaturity of the Australian program settings. The Australian program focuses on cash incentives to achieve voluntary returns. In Belgium, the available cash is clearly not an incentive for people to return, it is the cooperation of the voluntary and involuntary aspects of the program. The Belgian approach focuses on increasing subscription to voluntary return by demonstrating the ability to perform forced returns for the same migrant groups.

Norway

The Norwegian AVR program favours pay-to-go principles. In April 2016, the Norwegian Government offered a bonus payment of 10 000 kroner (approximately A$1600) on top of its standard voluntary return allowance of 20 000 kroner (approximately A$3200) to encourage certain migrant groups to return home.[9] The pay-to-go payments were targeted at failed asylum seekers and those migrants who were not entitled to asylum. The Norwegians also use pay-to-go payments to encourage departure for migrants who have a legal obligation to leave Norway, do not want to leave voluntarily, and are unable to be forcibly returned. For those subject to forced return, the program includes time-limited access to greater amounts of assistance, designed to produce quick agreement to depart.[10]

There are two key lessons for the Australian AVR program from Norway: the importance of accurately identifying the characteristics of migrant groups and designing returns policy to best accommodate those groups. Using pay-to-go principles broadly will not work, simply because there will always be migrants who are unable to be forcibly returned. For these groups, incentives for departure are unlikely to produce sustained departure results and will generally affect the integrity of such a policy.

An additional strength of the Norwegian program is the selective use of a service provider as a visible actor in the returns process. Recognising that some returning nationals want to return home without the visible assistance of a service provider and/or a host government, the Norwegian program offers debt-free cash grants to migrants who agree to return home voluntarily. The grant is paid at the departing airport and the migrant is able to return as a regular commercial airline passenger as though they have been abroad for a few years. This type of customised setting still meets government objectives while accommodating a caseload that may not want to prolong its engagement with government agencies or a service provider

Improving the Australian AVR program

There is an opportunity for the Australian Government to achieve a greater number of returns, particularly by focusing on defined sub-groups of migrants. Within the greater population of migrants who are required to leave Australia, there are opportunities to facilitate departure, as conveniently as possible, for visa overstayers and non-compliant student visa holders.

Drawing on the experiences of other countries, there are a number of ways to strengthen the Australian AVR program. It should be noted, however, that all of the following recommendations depend on two major factors: defining clear objectives for the AVR program (or clearer objectives than currently exist) and establishing a greater understanding among policymakers of what an AVR program can and cannot do. In particular, knowing the true capability of the AVR program will inform both diplomatic-level discussions on returns and program development to maximise returns.

Increasing competition and cooperation between service providers

Increasing competition between service providers is a simple non-policy change that can strengthen the Australian AVR program via a well-designed open tender process. The aim would be to increase the agility of service delivery, and maximise performance by including multiple service delivery agents. For example, there is the potential to engage multiple service providers to perform small parts of an engagement strategy, including outbound media and communications, active engagement with diaspora communities, and exploring the potential to engage via government and non-government social welfare groups. This service environment gives the program a truly multifaceted quality that focuses on events other than just putting people on planes.

Prioritising the relationship between voluntary and involuntary return activity

There is often a misperception about the ease with which a voluntary return program can produce departures on its own. This leads to a reliance on the program to move large numbers of migrants who are legally required to leave the country, and frustration when the numbers reduce to a trickle. There are two major interconnected points here; continual investment in forced return is required to drive subscription to voluntary returns programs, and consistent subscription to a voluntary return program relies on a visible, demonstrable capability to return some people against their will.[11]

Other enhancements allow for policy settings to work cooperatively with operational procedures, such as implementing strategies that favour enforcement activity. This overtly gives preference to the work of enforcement teams, and gradually takes voluntary decision-making away from those migrants who are legally required to leave Australia. These settings can be achieved in Australia by, for example, mandating a link between continual grant of a non-ongoing visa and acquiring a valid travel document or the permanent reduction in welfare payments. Guidance is available from the Canadian and British processes, which use forward-thinking policy models to guide the operational work of their enforcement teams.

Establishing sending alliances instead of regional returns alliances

Australia should seek to establish a sending alliance, which is different from the traditional return and readmission agreement. A sending alliance is a multilateral agreement between like-minded countries for returns to a particular part of the world. Australia’s position in its region has it as a sender of returns among many countries that are receivers of returns, sometimes the same returns, and this makes it challenging when it is time to form a regional returns alliance. For Australia, the search for partners to a sending alliance needs to be worldwide, and should include the possibility of establishing common standards for returns with like-minded countries.[12] This means Australia could form this alliance with other countries, irrespective of geographic location, that are returning migrants to the same destination. Australia’s involvement in a variety of international immigration forums provides a convenient way to start these conversations.

Establishing a sending alliance is also about creating returns agreements that are genuinely fit-for-purpose. Bilateral agreements are good, but only when linked to consistent sizeable returns caseloads. Compared to European Union (EU) members, Australia’s current bilateral agreements are not linked to large return numbers, and this makes it challenging to continually demonstrate the relevance of returns via these agreements. Additionally, the answer is not to spend more money on bilateral agreements in the hope that this will generate more returns. Australia’s current low return numbers suggest a broad formal agreement may not be the most conducive way of completing returns. A sending alliance would allow Australia to complete its existing returns as a member of a larger bloc approach. It also can provide links to more established returns networks for certain parts of the world, and the potential to complete returns for a lower cost.

By way of providing a working example, the ability of the EU to coordinate returns gives it a greater amount of bargaining power when negotiating returns with countries of origin. The ability for Australia to become involved in an EU-led returns effort may be limited, for the simple reason that EU returns arrangements may only be available to EU member states. But it is not uncommon for non-EU members to be involved in these arrangements, and Australia, like Norway and Switzerland, may be able to capitalise on EU returns agreements in the future under the auspices of a sending alliance.

Conclusion

While it is important to understand what the Australian AVR program is capable of achieving, some changes can be made to strengthen the existing program. In particular, ensuring it can accommodate changing migrant caseloads and genuinely serve the objectives of government.

Clear objectives for the AVR program are necessary to link government intent to policy, and then link policy to program design and function. This can begin with simple things, such as educating government about AVR program design and function, and how it can best serve its objectives.

There are challenges when attempting to introduce customised settings in any policy environment. The current Australian AVR program is strongly dependent on IOM to facilitate voluntary returns and this may need to change in order to appropriately future-proof the program. Part of the advantage of working with a service provider is sharing the administrative and operational burden of the AVR program and this will work for some host governments but not for others. Working with the right service provider(s) can help to ensure the program is customised to suit government objectives.

In-housing part or all of an AVR program also aids program governance, providing a seamlessness between policy objectives, program design, and program delivery. Government objectives must be inherent in policy and program design, and sometimes can remain at a distance when working via a service provider. Strengthening the relationship between voluntary and involuntary programs can also increase subscription to voluntary return programs. It is imperative that a returns program is intelligent enough to know when a voluntary return is unlikely to be achieved and when involuntary return will provide the best result.

Although AVR is able to form part of Australia’s migration management program, it is not a catch-all program. A good migration management program has many strong points such as timely processing of protection claims and mechanisms to defeat spurious access to judicial review. These, among other features, are able to enhance an entire migration management program. Facilitating return is not as easy as paying people to go home and requires the cooperation of multiple, complementary policies to produce the best results. Australia cannot simply offer return as an option to certain migrants and always expect departure to be the result. All policy that contributes to government objectives for return must be focused on maximising the performance of the overall migration management plan. Until this happens, the Australian AVR program is likely to remain overpriced and underutilised.

Acknowledgements

This working paper series is part of the Lowy Institute’s Migration and Border Policy Project, which aims to produce independent research and analysis on the challenges and opportunities raised by the movement of people and goods across Australia’s borders. The Project is supported by the Australian Government’s Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The views expressed in this working paper are entirely the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy or the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Notes

[1] Ben Doherty, “‘It’s Simply Coercion’: Manus Island, Immigration Policy and the Men with No Future”, The Guardian, 29 September 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/sep/29/its-simply-coercion-manus-island-immigration-policy-and-the-men-with-no-future.

[2] Emran Feroz, “In Europe, Afghan Refugees Anticipate Deportation”, Al Jazeera, 20 October 2016, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/10/europe-afghan-refugees-anticiapte-deportation-161018120108917.html.

[3] United Kingdom Home Office, Immigration Enforcement Voluntary Departure Strategies, 2015.

[4] The Immigration and Asylum Appeals (One-Stop Procedure) Regulations 2000 , http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/2244/made.

[5] Intangible Governance, “Evaluation of the Reintegration Component of Canada’s Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) Pilot Program”, 2014, 3.

[6] “Programmes and Strategies in Belgium Fostering Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration in Third Countries”, European Migration Network, Belgian National Contact Point, October 2009, 7, https://emnbelgium.be/sites/default/files/publications/programmes_in_belgium__fostering_assisted_voluntary_return.pdf.

[7] Ibid, 3.

[8] Federal Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers, “Reintegration”, http://fedasil.be/en/content/aid-reintegration.

[9] Chiarra Palazzo, “Norway Offers to Pay Asylum Seekers £1000 Bonus to Leave the Country”, The Telegraph (UK), 26 April 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/04/26/norway-to-pay-asylum-seekers-extra-money-to-leave/.

[10] Richard Black, Michael Collyer and Will Somerville, Pay-to-go Schemes and other Non-Coercive Return Programs: Is Scale Possible? (Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2011), 8, http://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/pay-to-goprograms.pdf.

[11] Ibid, 17.

[12] “Non-binding Common Standards for Assisted Voluntary Return (and Reintegration) Programmes Implemented by Member States”, Council of the European Union, 11 May 2016, 2, http://statewatch.org/news/2016/may/eu-council-assisted-voluntary-returns-non-binding-standards-8829-16.pdf.

About the author

Glen Swan is a policy officer at the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, working on Australia’s assisted voluntary returns program since 2012. He completed a fellowship with the Lowy Institute in 2016.