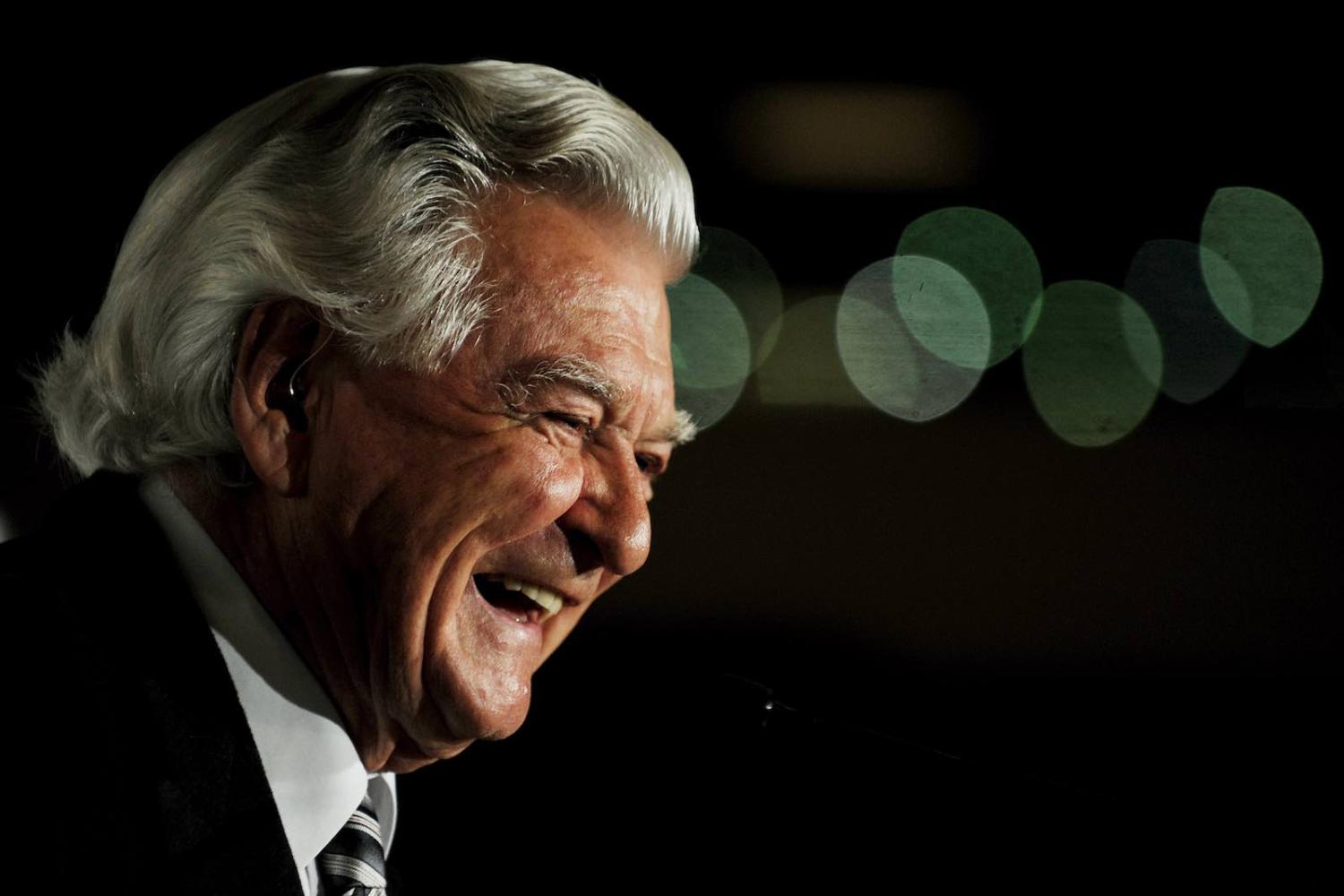

Australia has never had a prime minister quite so convinced of the power of human agency as Bob Hawke. Hawke never doubted his own capacity to persuade. And the secret of persuasion, and of any good negotiation, was to identify the interests of the various players and bring them together in search of common ground. Like many of those working around him, I heard the Prime Minister, an avid punter, recount the maxim that in the race of life you should always back the horse called “Self-interest”: at least you knew it was trying.

That applied to foreign policy as well. He set great store by personal relationships, and those he developed with people such as US Secretary of State George Shultz, the Chinese Premier, Zhao Ziyang, and the Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, mattered at critical times.

But it was structure rather than agency that provided the foundation for the successful foreign policy of the Hawke years. Memories of the policy mistakes and political chaos of the Whitlam government weighed heavily on Hawke and his colleagues. Processes and discipline – above all his own self-discipline – were central to Hawke’s achievement. His effective chairing of cabinet, the space he gave his ministers and the respectful way he worked with the public service were all essential to policy success. He chose as his successive chiefs of staff some of Australia’s most capable diplomats.

Although Hawke had only been in parliament for a short time when he became Prime Minister in 1983, he had extensive experience in international affairs through his role in the Australian Trades Union movement and the International Labour Organisation in Geneva.

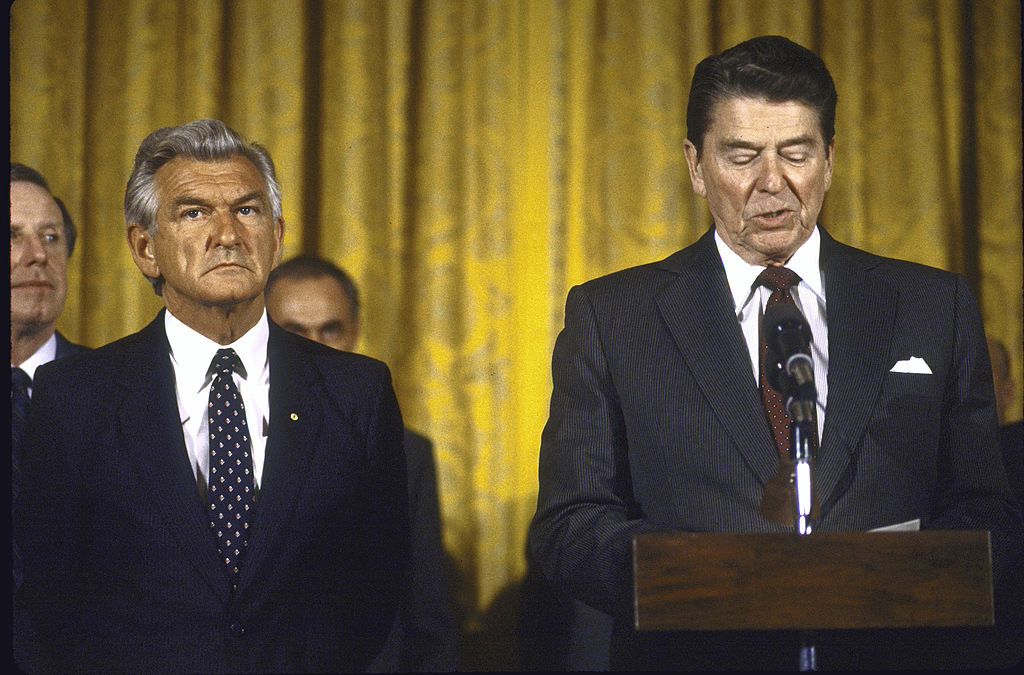

These were years of rising international tensions. Ronald Reagan, elected as US president two years earlier, had abandoned the policy of détente. The Cold War was heating up. Reagan had begun to confront the Soviet Union, which he labelled an “Evil Empire”, with a huge American defence build-up. Across the Atlantic, his closest international supporter, Margaret Thatcher, had embarked on her radical program of transforming the British economy and society. With fears of conflict growing, new fractures were appearing in many Western societies, and nuclear disarmament movements were growing in strength. An estimated 250,000 people marched in Palm Sunday peace rallies in Australia in 1984.

The new Prime Minister was keen to reassure the suspicious Republican administration in Washington that this was a different sort of Labor government. He kept the Liberal Party grandee Sir Robert Cotton in place as ambassador in Washington and made an early visit himself to reinforce the message that the alliance was not at risk.

But many elements of his own party were suspicious of Reagan and divided about the ANZUS alliance, especially the role of the secretive Joint Facilities. In 1984, Hawke was forced into a humiliating backdown over Australia’s role in monitoring tests of the new long-range American multi-warhead MX missile when details were leaked in the press. He was rescued from embarrassment by Shultz, who was an old acquaintance from the ILO.

The remaking of the Australia-US alliance for the times may have been Hawke’s greatest contribution to Australian foreign policy.

The remaking of the Australia-US alliance for the times may have been Hawke’s greatest contribution to Australian foreign policy. It’s hard to think of another leader who could have managed it so effectively. He worked closely with his second Defence Minister, Kim Beazley, another firm friend of the alliance, but he also drew on the more sceptical positions of his two foreign ministers, Bill Hayden, his defeated rival for the Prime Minister’s job, and Gareth Evans.

A review of the ANZUS treaty was undertaken. Australia’s role in the joint facilities was renegotiated and their function made more public. They were (correctly) explained as an important element in the strategy of deterrence which helped prevent nuclear war. Australia’s position was to be one of “self-reliance within the alliance”. It was never quite clear what that meant but it reflected a conceptual balance with which the Australian people were clearly comfortable. The contrast with the breach with Washington under the Labour government of David Lange in New Zealand was marked.

Important changes were also underway in Australia’s own region. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, begun in December 1978, were starting to transform China. New demand for Australian resources and energy was driving trade to new levels. Australia became a testbed for China’s overseas investment. “A substantial relationship … acknowledging China’s important role in the region and the world should be central to Australian foreign policy”, Hawke declared in 1984.

The idea of “enmeshing” Australia with Asia was central to Hawke’s policies. Ross Garnaut, earlier his economic adviser and ambassador in Beijing, was commissioned to prepare a report on “Australia and the Northeast Asian Ascendancy”. Hawke himself launched the APEC process for regional economic cooperation during a visit to Seoul in 1989.

He invested a great deal in his own relationship with Chinese leaders such as Premier Zhao Ziyang and the Communist Party Secretary Hu Yaobang. His tears as he addressed a public meeting in the Great Hall of Parliament House after PLA soldiers shot down demonstrating students in Tiananmen Square in June 1989 reflected his dashed hopes for a different sort of relationship.

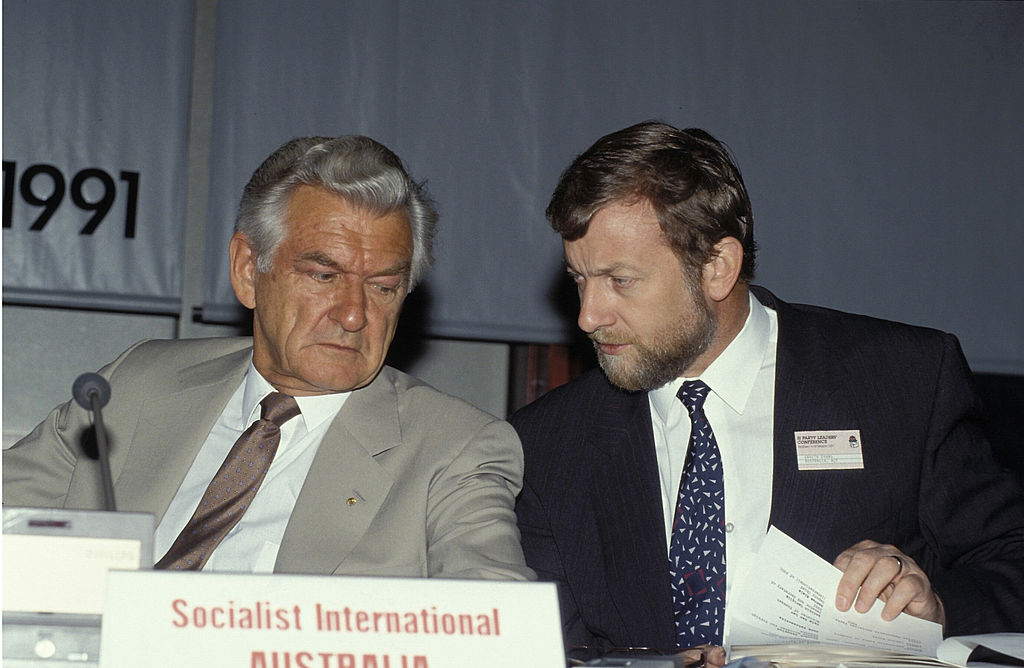

It was a comprehensive foreign policy. In those years before the G20 and Summit Season, the Commonwealth was still the principal international forum in which an Australian Prime Minister could operate. Through the late 1980s, in the face of staunch opposition from Thatcher, Hawke used Commonwealth meetings and allies including India’s Rajiv Gandhi and Jamaica’s Michael Manley to ratchet up the pressure on South Africa to end apartheid. Hawke’s particular role in persuading American and European banks to add financial sanctions to existing trade and sporting bans was an important element in the release from prison of Nelson Mandela and the final dismantling of apartheid.

Hawke initially prompted, and later supported, the work of Hayden, then Evans, in working towards a peace settlement in Cambodia.

Since his trade union days, Hawke had close ties to the Israeli labour movement and a long-standing interest in the turbulent issues of Middle East peace. He was proud of his efforts to persuade the Soviet leader, Mikael Gorbachev, to release a list of Soviet Jews for immigration to Israel in 1987. A couple of efforts, including in the early stages of the First Gulf War in 1990, to offer his services as a negotiator found no traction, however.

In the multilateral area, there were substantial arms control successes, including the South Pacific Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, the creation of the Australia Group to improve export controls on substances used to make chemical weapons, and the Chemical Weapons Convention itself.

Hawke’s was the first Australian government to incorporate the environment as a central foreign policy issue. He appointed Australia’s first ambassador for the environment in 1989. His own role in the preservation of Antarctica as a wilderness was important.

There were lacunae. He was less comfortable dealing with the more allusive cultures of Southeast Asia and Japan. The relationship with Indonesia, strained by East Timor, was left that way. At times, he had too much confidence in his own powers of persuasion.

But the foreign policy legacy he left, balancing Australia’s different interests, broad in its ambitions and effective in its delivery, was one of substance.

Allan Gyngell is the author of Fear of Abandonment: Australia in the World since 1942. He worked in the International Division of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet from 1989 to 1993.