The Indonesian government lost a “citizen lawsuit” last month against 32 Jakarta residents after the court ruled that the defendants, which included President Joko Widodo, had responsibility for controlling air pollution in the capital city. The decision also pointed a finger at the governors of neighbouring West Java and Banten, as air pollution from their provinces had affected Jakarta.

The decision is fascinating, given a report last year from the Centre for Research, Energy and Clean Air claimed that the “airshed” covering Jakarta extends far beyond its administrative boundaries to include Central Java and Bogor. This was attributed in part to meteorological factors and industrial zoning of surrounding regions. But the problem extends much further. During the southwest monsoon period in spring, smoke haze from land and forest fires in Indonesia can even cause particulate matter pollution at levels considered damaging to human health as far away as Singapore.

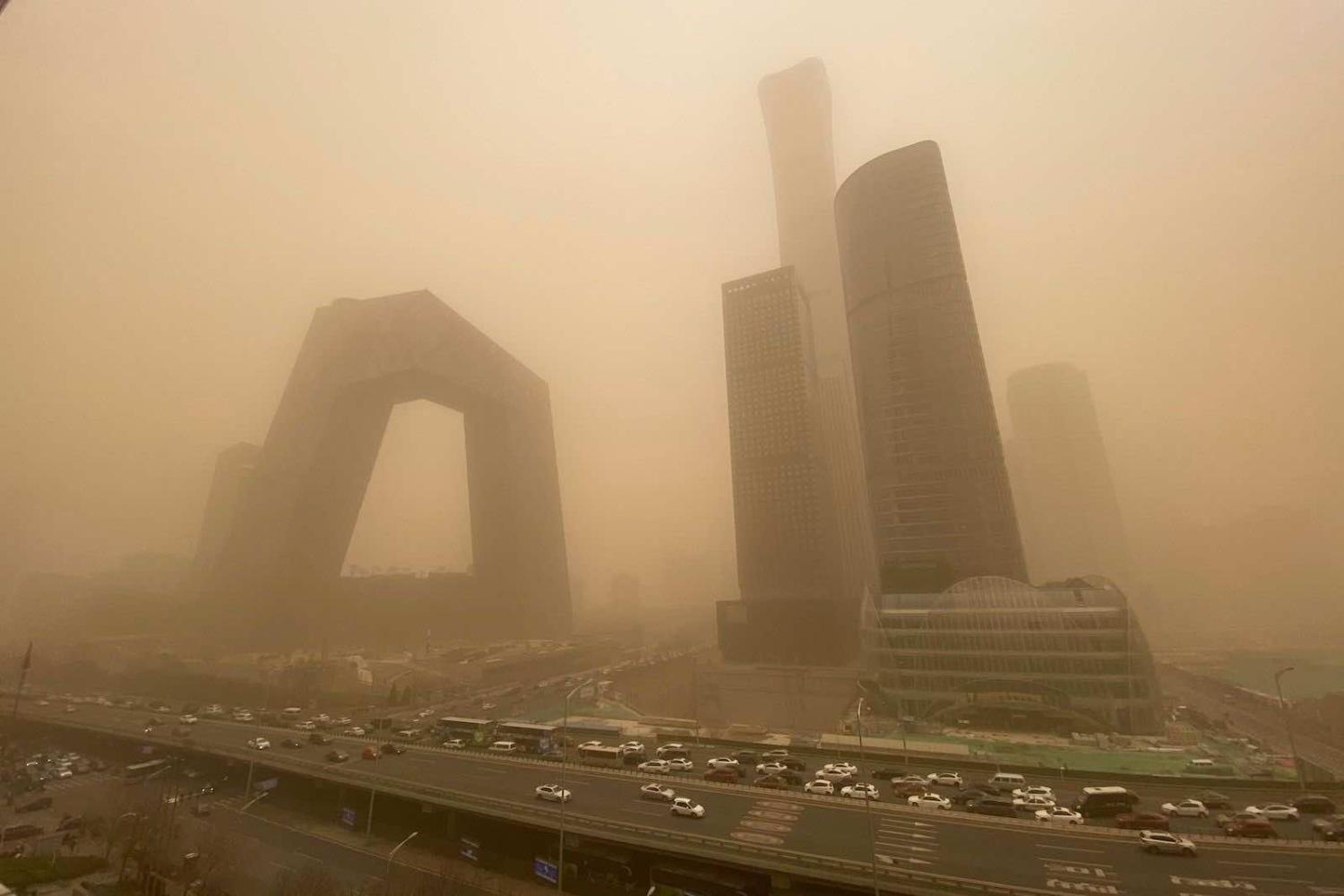

Air pollution does not respect national borders. At the beginning of January 2020, smoke from bushfires in Australia lead to haze in the South Island of New Zealand. In May this year the journal Environment and Development Economics published an article which linked days with high levels of particulate matter in China’s capital of Beijing to a 7.4 per cent increase in foetal deaths in South Korea.

On 22 September the World Health Organisation announced its new global air quality guidelines. First published as the WHO air quality guidelines for Europe in 1987, a global update was published in 2005. The update this year has greatly reduced what is considered to be the acceptable levels of a range of pollutants including particulate matter, ozone, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide. While not binding, the guidelines can be used by individual countries to set air quality standards. One of the architects of the new guidelines, Queensland University of Technology professor Lidia Morawska, captured the challenge when she said “breathing is not a choice”.

Most countries will exceed the new acceptable levels in some locations. In Australia, that will most often be in the cities. In 2019 more than 90 per cent of the global population lived in areas where air recorded air quality exceeded the 2005 guideline levels. The WHO estimate that 7 million people die annually from poor air quality, and many more lose several years of life expectancy.

Air pollution can affect brain and foetal development, result in diseases in almost all organs, and hasten the progress of chronic diseases such as dementia, asthma and diabetes.

While death rates caused by outdoor air pollution have reduced in about half the countries worldwide, they have also increased in around half mostly low or middle income countries.

In Asia the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre measures the passage of smoke haze and other air flows between ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia, but a regulatory framework is lacking. A global assessment of air pollution legislation found that only one in three countries have legal mechanisms for managing or addressing transboundary air pollution, and only 43 per cent have a legal definition of air pollution. This assessment recommends measures to fortify air quality governance, such as a common global legal framework for ambient air quality standards and regional legal instruments which can hold member countries responsible and accountable.

One of the first international instruments to better regulate air pollution between countries, the 1979 Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution is an example of successful international cooperation to reduce the risk of transboundary air pollution based on an initial goal to prevent acid rain. 51 countries in Europe and the Americas are signatories to the convention, which includes eight protocols to address negative health and environmental consequences of excess pollutants such as ozone, black carbon, heavy metals and particulate matter. It is widely regarded as an example of successful international environmental cooperation, with significant reductions in sulphur and other pollutants attributed to it .

However, while death rates caused by outdoor air pollution have reduced in about half the countries worldwide, they have also increased in around half mostly low or middle income countries, causing more than 2 million deaths annually in Southeast Asia. There are also high concentrations of particulate matter in the Middle East, north Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa due to high concentrations of desert dust, which itself is predicted to increase due to climate change.

It is clear that there are many affinities between efforts to reduce carbon emissions and to improve air quality. Decarbonising transport and energy and reducing reliance on combustible and fossil fuels will have the dual benefits of improving physical health and the stability of the atmosphere. With the COP26 global climate summit about to get underway this month in Glasgow, participation in global events and international covenants are still critically important for reducing carbon emissions and reaching those elusive WHO targets for air quality.