An end-of-year series as the Lowy Institute staff and Interpreter contributors offer their favourite books, articles, films or TV programs this year. Look back on more recommendations and reflections.

Okay, so 2020 wasn’t exactly a favourite year. I did learn how to bake a nice sourdough during Melbourne’s long lockdown. Didn’t nearly get through my reading pile. But I’ve been working in isolation for years now, so I really don’t have any excuses.

One book I did manage was historian and columnist Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya, a compelling biography of influential Soviet spy Ursula Kuczynski, a name not often heard in modern espionage folklore. While the Cold War turncoats such as the Cambridge Five or the Aldrich Ames’s typically garner most attention, Kuczynski was an agent handler in the war years, the hidden conduit to pass ill-gotten treasure back to Moscow. As a marker of Kuczynski’s tradecraft – and the damage she wrought – she was a key player in stealing the secrets to the atomic bomb.

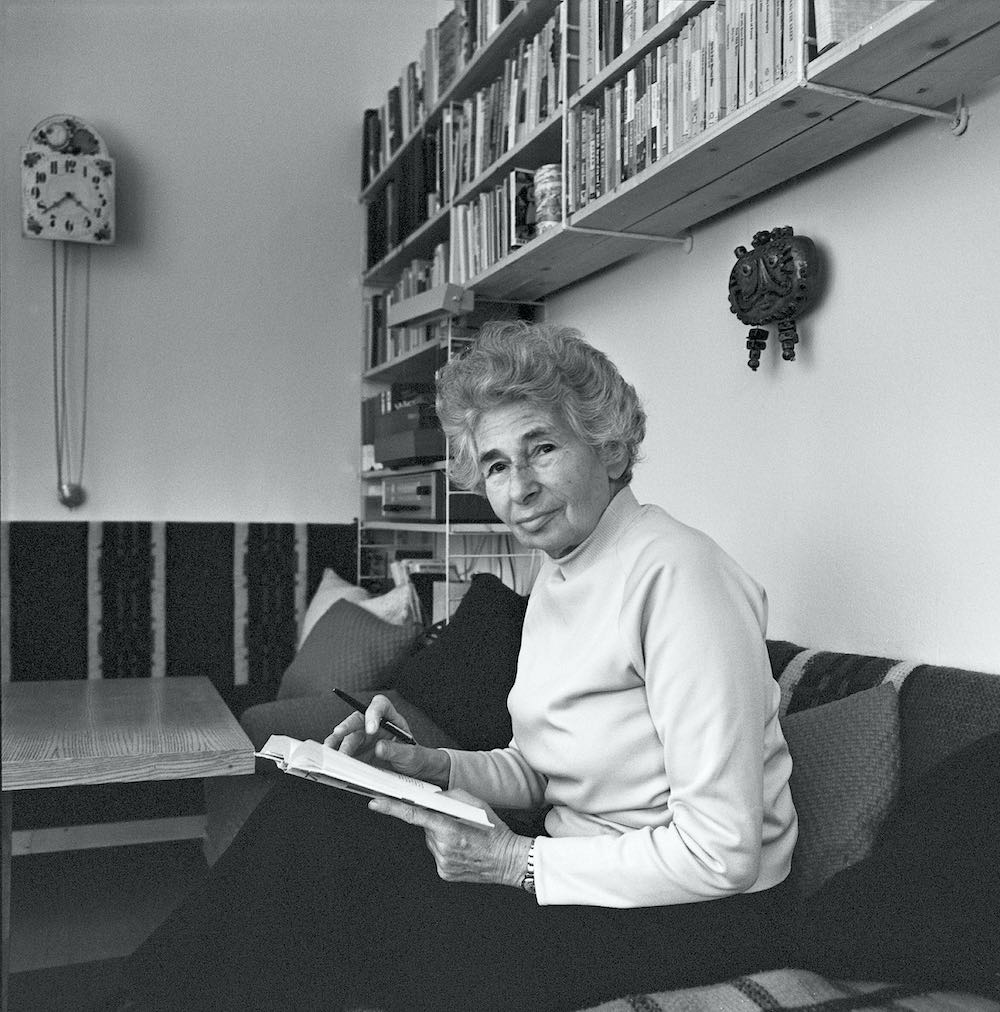

Kuczynski is only briefly mentioned in the 2009 authorised history of Britain’s counter-espionage agency MI5, in the context of the chauvinist conceit long pervading Western security services. Even in the 1970s, official minutes recorded “agent-running was a predominantly male preserve”. Macintyre attributes such sexist assumptions along with her evident talents to Kuczynski’s success. In 1940s Britain, she adopted the outward appearance of a housewife living in the English countryside – not entirely above suspicion for the spy catchers, thanks to her past radicalism and background as a foreigner, but if anyone was to be watched, so went the thinking of the time, surely it was the husband.

Kuczynski is only briefly mentioned in the 2009 authorised history of Britain’s counter-espionage agency MI5, in the context of the chauvinist conceit long pervading Western security services. Even in the 1970s, official minutes recorded “agent-running was a predominantly male preserve”. Macintyre attributes such sexist assumptions along with her evident talents to Kuczynski’s success. In 1940s Britain, she adopted the outward appearance of a housewife living in the English countryside – not entirely above suspicion for the spy catchers, thanks to her past radicalism and background as a foreigner, but if anyone was to be watched, so went the thinking of the time, surely it was the husband.

“Running the largest network of spies in Britain”, Macintyre writes, “her sex, motherhood, pregnancy and apparently humdrum domestic life together formed the perfect camouflage”.

Macintyre’s book is detailed – at times frustratingly so. The array of characters, locations and connections is difficult to follow, yet satisfyingly complete when Kuczynski’s story coalesces. Born in Germany in 1907, Kuczynski was influenced by the revolutionary zeal of communism in her youth, a radicalism solidified during the disastrous Weimar Republic years in opposition to the rising tide of Nazism and the prejudice against her Jewish heritage. She spent a year living in New York as the grip of the Great Depression took hold, eventually travelling across the world to Shanghai and into a spy’s double life.

The China networks she traversed in the 1930s are fascinating, her story a glimpse of the dangerous great power jostling in the “Far East”, with consequences extending to the present. She became “Sonya”, the code name the Soviets bestowed on the woman who rose to the rank of colonel in the Red Army (she was apparently for a long while oblivious to her rank). Her story is also bound to another long-standing controversy, whether Roger Hollis, a man she may have met in Shanghai in the 1930s, who would later become MI5 chief in the 1950s and 1960s, was in fact himself a Soviet spy, a claim Macintyre gives short shirft.

In Macintyre’s rendering, Kuczynski comes across as both warm and tiresomely didactic, contradictory traits that perhaps allowed her the compassion to establish trusting connections yet the intellectual rigidity to maintain strict faith in the cause. Her relationships are loving, whether with her children or the three men who fathered each over the years – yet always subordinate to her clandestine commitments. Neither Stalin’s vicious purges nor the loss of agents would turn her from the revolution.

Her story extends to Switzerland in the first years of the Second World War, where she furtively established a radio transmitter and dodged detection, fusing her family life to her secret one. Tedium was oftentimes a feature of her double life – the drudgery not a result of parenting, but transcribing signals late at night or muddled plans for secret rendezvous (a mistaken tree root meant as a dead-drop location to pass messages would later lead her to lose contact with Moscow for months).

It was after fleeing to Britain in 1941 that Kuczynski’s value as a non-Russian spy for the Soviet Union would be truly exploited, an “illegal” operating without the ostensive protection of diplomatic cover, exposed yet so much more difficult to detect.

Kuczynski was the secret go-between for Klaus Fuchs, the brilliant German-born British theoretical physicist as he worked first on Britain’s wartime attempts to construct a nuclear weapon, all the while handing hundreds of pages of formulas and research to the Soviet Union. She later ensured Fuchs connected to another Soviet agent in the United States after he travelled to work on the Manhattan Project. When Fuchs was eventually exposed in 1950, the net closed around Kuczynski, yet once again gendered assumptions about her true role and a little luck meant she could escape – returning to where her story began, to live the revolution as she had dreamed since a girl in a Communist Germany (East, anyway).

The story centres on Marie Mitchell, a young FBI agent who is recruited by the CIA in the late 1980s to spy on

The story centres on Marie Mitchell, a young FBI agent who is recruited by the CIA in the late 1980s to spy on

In Homeland Elegies, Akhtar first braids then unravels the strands that make up American identity and mythmaking – the immigrant experience, unabashed capitalism, individualism, the promise of hard work and the rule of law. In a post-truth, post-fact era, it is particularly fitting that Akhtar’s narrative purposefully obfuscates what is fiction and non-fiction, because in so doing, he clears up what has been obscured by the reflexive belief in America’s founding myths.

In Homeland Elegies, Akhtar first braids then unravels the strands that make up American identity and mythmaking – the immigrant experience, unabashed capitalism, individualism, the promise of hard work and the rule of law. In a post-truth, post-fact era, it is particularly fitting that Akhtar’s narrative purposefully obfuscates what is fiction and non-fiction, because in so doing, he clears up what has been obscured by the reflexive belief in America’s founding myths.

China is likely the first country that springs to mind when hearing the words “state-owned enterprise”. But governments play significant roles in many Southeast Asian economies too, with Malaysia’s infamous 1MDB scandal showing how such involvement can go awry. Launching off the 1MDB story, MoF Inc pulls back the curtain on Malaysia’s government-linked investment companies (GLICs) more broadly. The book delves into what they are (vehicles for the government to invest in companies), how they’ve been used across various political regimes (to drive development and to bail out failing private companies) and the control they have over Malaysia’s corporate sector.

China is likely the first country that springs to mind when hearing the words “state-owned enterprise”. But governments play significant roles in many Southeast Asian economies too, with Malaysia’s infamous 1MDB scandal showing how such involvement can go awry. Launching off the 1MDB story, MoF Inc pulls back the curtain on Malaysia’s government-linked investment companies (GLICs) more broadly. The book delves into what they are (vehicles for the government to invest in companies), how they’ve been used across various political regimes (to drive development and to bail out failing private companies) and the control they have over Malaysia’s corporate sector.