Yang Jie, an intern in the East Asia Program, and David Vallance, an intern in the International Security Program, summarise media reports from across the region following the release last month of the Foreign Policy White Paper.

China

- People’s Daily, ‘China has serious concerns about Australia’s “irresponsible” remarks on the South China Sea’

中方严重关切澳方涉南海’不负责任’言论

When asked for comments on the White Paper, Lu Kang, spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, urged Australia to ‘stop making irresponsible remarks on the South China Sea’. On the rules-based order, Lu stresses that China has always supported an order under the framework of the UN. ‘The order we are talking about is not dictated by any country’, the spokesperson said, indicating that China respects a rule-based order, but the order is not necessarily made by the US or Australia.

Comment: Lu’s remarks suggest China is annoyed by Australia’s comments on the South China Sea, yet not especially angry with Australia’s suggestion that China is challenging the rules-based order. China considers Australia’s stance on the South China Sea unhelpful in maintaining the stability of the region. Chinese media reports stressed that China and ASEAN countries have made significant progress in dealing with the South China Sea issue, suggesting this progress is disrupted by Australia’s continuous raising of the issue and calls for other countries to counterbalance China.

- Global Times, ‘Editorial: Australia is biting the hands that feeds it’

社评:澳大利亚端起碗吃肉,放下筷子骂娘

The Global Times adopted a harsher tone on the White Paper. Its Chinese language title literally read ‘Australia eats the meat and then abuses the mother’, suggesting that Australia is not grateful for the benefit it has gained from China.

‘Most of western countries have an anxiety about the rise of China, but Australia has the most blinkered approach towards the rise of China,’ the article said. ‘While the US even somehow expresses its welcome to China’s rising, Australia seems to hold a negative attitude itself and [is] steering others to this direction’. Indeed, the Global Times has, for a while, accused Australia of serving as a distant propaganda outpost agitating for neighbours to be wary about China.

The Global Times writes that ‘Australia is difficult to be reasoned with or be comforted. Fortunately, the country is not that important and China can move its ties with Australia to a back seat and disregard its sensitivities.’

Comment: The Global Times also featured a surprisingly self-reflection, asking why it is so hard for China to employ soft power and make other countries comfortable with the rise of China.

- Global Times, (English language edition) ‘Progressive Australian views will win out over parochial Foreign Policy White Paper’

‘It remains to be seen if Australia's establishment would come to trust China anytime soon to lead our world at a time of an increasingly myopic American leadership that is too self-obsessed with its own identity politics and endemic US socio-economic problems’, the author says. ‘My bet is that the Australian common progressive sense will prevail over provincial loyalties’.

- Global Times, (English language edition) ‘White Paper reveals Australia’s anxiety’

The article says Australia, now and in the past, has sought ‘to meddle in Asian affairs on behalf of the West’ and concludes by downplaying the importance of Australia to China. It finishes: ‘Australia after all is not part of the Asian continent. China should prepare both a friendly face and a cold shoulder’.

India

- Times of India, ‘Growing role for India in Australia’s new foreign policy document’, by Indrani Bagchil

The ‘Quadrilateral Dialogue’ appears in the first sentence of this article, as an example of the potential increase in Australian engagement with India. However, Bagchil is quick to note that support for the Quad is not uniform in Australia, stating that Labor has still not ‘signed off’ on it. Australian engagement with India will not only involve attempts to resuscitate the Quad, but also participating in naval exercises with the Indian military. The article notes that the coming India strategy paper will complement the conclusions and recommendations drawn from the White Paper.

Finally, noting Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s support for the rules-based international order, Bagchil quotes The Australian columnist Rowan Callick saying that China may increasingly perceive Canberra’s foreign policy as a 21st century version of containment.

New Zealand

- New Zealand Herald, ‘Australia-NZ relationship central to regional security: White Paper’, by Nicholas Jones

This brief article emphasises the acknowledgement in the White Paper of the importance of Australia-NZ cooperation in economic, defence, and intelligence matters as ‘Australia’s most comprehensive relationship’. New Zealand’s role as a member of the Five Eyes partnership for intelligence cooperation is emphasised, as is its role in enhancing Australia’s engagement with Pacific island countries.

Singapore

- Straits Times, ‘The Great Aussie Dilemma’, by Ravi Velloor

This article is one of the few substantive pieces of analysis on the White Paper written outside Australia. Velloor begins by praising the way in which Australia’s foreign policy establishment recognises the connection between ‘geopolitics and geo-economics’. The paper, he goes on to say, is a ‘magnificent tour de force’ as a view of how the Indo-Pacific will develop in the coming decades.

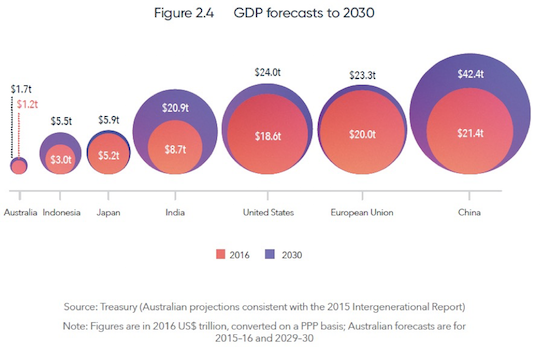

On the economic front, he has no concerns. The White Paper notes that by 2030 the region will produce more than half of global economic output, and consume over half its food and 40% of its energy. It is natural that Australia should seek to engage in growing markets.

His misgivings are towards the foreign policy part of the White Paper. He poses the question of whether Australia puts too much ‘blind faith’ in the US, and whether solutions put forward to check Chinese aggression are indeed workable. American retrenchment is not the product of the Trump administration alone, he says, and there is no guarantee that subsequent administrations will take a harder line against China in the future. The suggested foreign policy, he says, has whiffs of containment about it, and has a certain nostalgia for the relative simplicity of the bipolar Cold War world order.

The main ‘dilemma’ he would see resolved is between ‘the US for security, China for prosperity’. One indication of Canberra’s willingness to ‘stay the course’ against Chinese aggression, Velloor says, would be if Canberra decided to conduct freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea. Until then, or until another hard power action occurs, the dilemma will remain unsolved.