It is not often that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) gets involved in a national referendum, but that is exactly what recently occurred when South American country Guyana requested the court to order that neighbouring Venezuela not proceed with a 3 December ballot.

It is also rare that citizens are asked to endorse a government proposal to annex the territory of a state next door. Yet this also was one of the questions that was put to Venezuelans in the referendum, which went ahead last weekend.

According to official Venezuelan referenda results, there was an overwhelming 95 per cent vote in favour of the five questions posed. Venezuela is now in the process of putting in place legal mechanisms to seize part of what has to now been Guyana. Meanwhile, Guyana, is seeking to bolster diplomatic support for its position and there is every prospect the territorial dispute may soon be debated in the United Nations Security Council.

The disputed area comprises 159,500-square-kilometres (61,600-square-miles), more than two thirds of Guyana’s territory, larger than the territory of North Korea, and roughly twice the size of Tasmania. While the world has been fixated on the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, and the ongoing Ukraine conflict, how did this Latin American territorial dispute suddenly become so intense?

History and context is important in all territorial disputes. Venezuela emerged as an independent state in 1830. It shared a border with British Guyana, which itself was a former Dutch colony before becoming British in 1815. Guyana achieved independence in 1966, and the two countries share a 789 kilometre land border that extends from a southern tri-point with Brazil to the Atlantic coast.

As was common in the 19th century, the colonial boundaries were poorly drawn and subsequently disputed. An Arbitral Tribunal met in Paris from 1897, with an award handed down in 1899. The Paris Award resulted in a 1905 formal demarcation of the Guyana-Venezuela border and official boundary maps were produced following confirmation of the agreed co-ordinate points. Ninety per cent of the disputed area was awarded to Guyana.

The boundary was significant for three reasons: it confirmed Venezuela’s claim to the Orinoco Delta adjoining the Atlantic, that Guyana’s territory extended west of the Essequibo River to the border, and title over the adjacent coastlines. As the law of the sea developed throughout the 20th century, the respective coastlines of Guyana and Venezuela gradually became more economically significant as they were the foundation for the assertion of offshore Atlantic maritime claims in areas considered to have plentiful oil and gas reserves.

An extraordinary development occurred in 1962, when Venezuela alerted the United Nations to the existence of a dispute with the United Kingdom over the land boundary. Venezuela asserted the 1899 Paris Award was fraudulent due to alleged collusion between the arbitrators to find in favour of Britain, which at the time was the colonial power. Venezuela’s claim sparked a series of diplomatic processes that first resulted in the 1966 Geneva Agreement, various UN efforts at diplomatic resolution of the dispute, until finally in January 2018 the current UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, referred the matter to the ICJ. The dispute has since been centred in The Hague, however, recent events have focussed global attention on what to date has generally been a low key diplomatic and legal dispute.

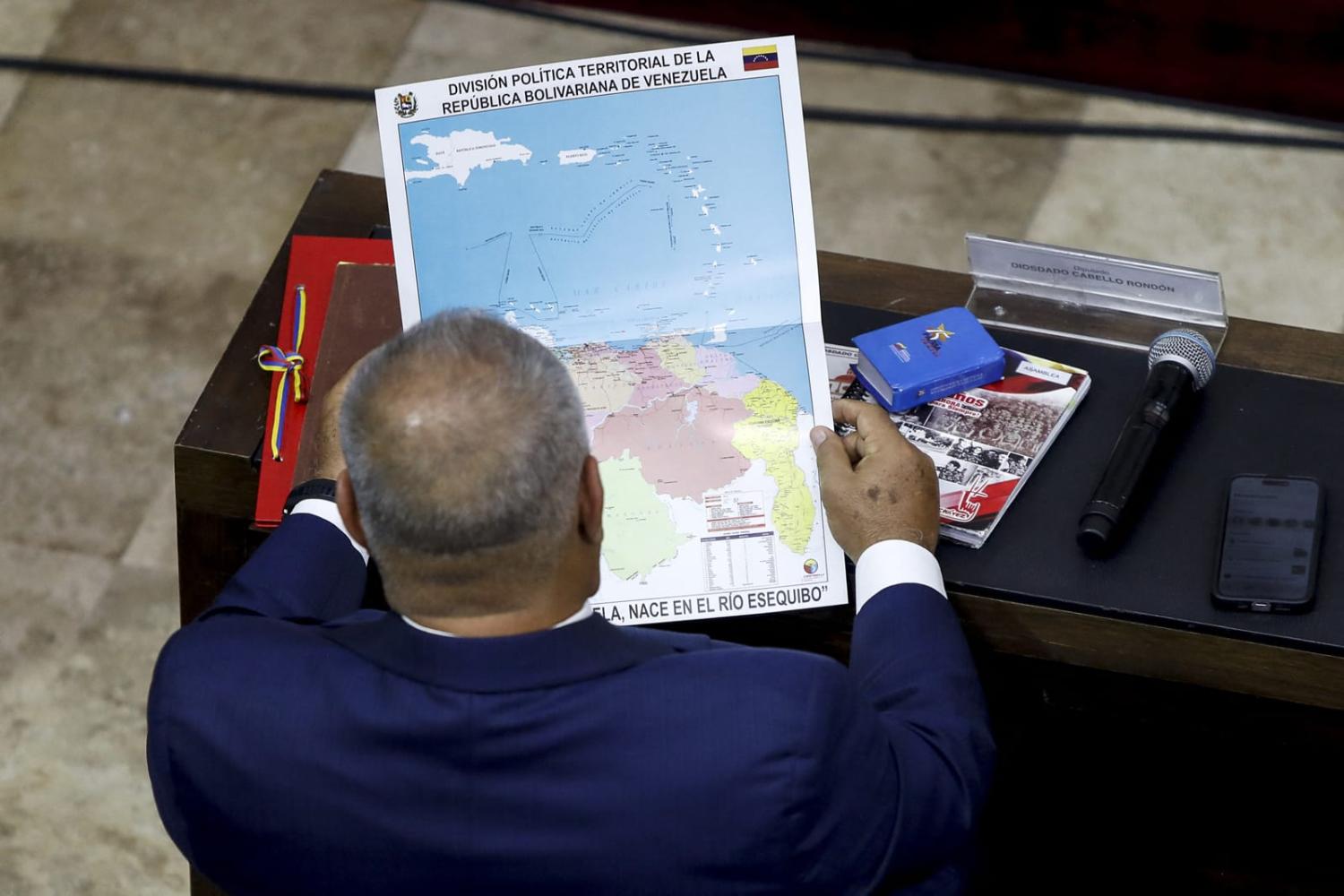

On 20 October this year in Caracas, the government of Nicolás Maduro announced plans for the 3 December Consultative Referendum. Five questions were posed which raised the legitimacy of 1899 Paris Award boundary and the 1966 Geneva Agreement, the ICJ proceedings commenced by Guyana, Venezuela’s Atlantic maritime claims, and finally Venezuela’s aim to acquire the disputed territory. In particular the fifth question asked: “Do you agree with the creation of the Guayana Esequiba State and that an accelerated and comprehensive plan be developed for the present and future population of that territory … incorporating that State into the map of Venezuelan territory?”

The ICJ unanimously issued provisional measures on 1 December that made clear that Venezuela was to “refrain from taking any action which would modify the situation that currently prevails in the territory in dispute”. Nevertheless, Venezuela proceeded with the referendum, and on the basis of the result is moving forward with its plans to effectively annex the disputed territory. It has been reported that Maduro has asked for new laws to be drafted that recognise Guayana-Esequiba as a new Venezuelan state. Guyana has appealed to the UN and the United States for assistance.

Venezuela’s response to the ICJ ruling is a complete repudiation of the processes António Guterres put into place to resolve the dispute, which to date had been gradually making its way through various phases of ICJ hearings and determinations on preliminary jurisdictional matters. Now that there is a clear and legally binding provisional measures ruling having been issued by the court, Guyana has the option to take the dispute to the Security Council and seek Article 94 measures to give effect to that judgment. However, given the close relations between Russia and Venezuela, a Russian veto could block any effective Security Council response. Guyana, meanwhile, is reported to be preparing to defend its territory.

Territorial disputes have a history of suddenly flaring after a long period of apparent calm and become a catalyst for fierce nationalistic fervour. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine highlights this dynamic. Maduro will now claim a popular mandate to defy the ICJ. That would be yet another test of the UN system and rule of international law. Doubts have been raised as to the referendum’s legitimacy with international media reporting a very low turn-out. Venezuela has planned 2024 presidential elections and Maduro may be using these events to bolster his re-election prospects. Whether the international community, and particularly the United States, has any remaining energy to devote to peacefully settling this latest territorial dispute remains to be seen. All indicators are pointing to the need for a swift response.