Outward bound

Australian businesses are confident about foreign markets despite the threat of a global trade war and doing it without the need for new digital commerce channels to find customers.

These are the two striking findings from the latest Australian International Business Survey (AIBS), which now provides one of the richest sources of information on how globalisation is occurring at the grassroots of the economy.

And business continues to have a fairly even bet on the US and China as the source of future revenue growth amid growing security tensions, although there has been a drift towards the US in the last few years as its economy has recovered and China has slowed.

The latest survey also shows a stronger interest in India and Indonesia as future growth markets than their current status as economic partners. This vindicates the serpentine efforts governments have been pursuing with these two countries to secure new bilateral economic frameworks.

Australian businesses are reluctant are to follow export success with investment abroad. Instead, exporting is the main form of international engagement for the majority of businesses.

The survey, conducted by Austrade, the Export Council of Australia and the Export Finance Insurance Corporation, shows a steady upward trend in optimism about international business activities from 47% in 2016 to 66% in this year’s results. There is also a clear connection to increased employment, which should make these figures useful for the two major political parties facing some discontent about globalisation in their ranks.

But curiously, in the era of Amazon and Alibaba, the proportion of these foreign focussed businesses using e-commerce has fallen from 53% in 2016 to 44%. The company website is far the most dominant channel for this diminished ecommerce at 43%, compared with 14% for Facebook.

These surveys are now showing a consistent pattern of English language countries (the US, United Kingdom, and New Zealand) being the jumping off point for businesses going abroad and, with the addition of China, they remain the top revenue generators. But when it comes to new business prospects, Indonesia, India, and Vietnam each leap up the ranks, with some strong interest in Germany and Japan as well.

The survey provides a mixed contribution to the debate about Australian businesses being reluctant to follow export success with investment abroad. Exporting is the main form of international engagement for 60% of businesses, while only 23% are pursuing offshore investment.

But investing abroad in risky greenfields operations appears to be regarded as more important to growth than either investing abroad through acquisitions or seeking foreign investment at home.

Chinese numbers game

Australia now has a fifth data source on Chinese foreign investment, underlining how this has become one of the most politically vexed numbers in national policymaking.

The Australia National University has drawn together a consortium including the Federal Treasury, the Reserve Bank, PwC, and Macquarie Bank to produce the new database that shows Chinese investment of $40.6 billion over the past four years.

As I have previously identified (here and here), the existing data sources produce quite different figures for Chinese investment due to different methodologies, which has allowed commentators to draw on figures which suit their argument. The Foreign Investment Review Board approval numbers point to investment of $160.5 billion in that four-year time, while the Australian Bureau of Statistics investment series suggests $17.8 billion.

The new ANU system broadly parallels the numbers thrown up by the American Enterprise Institute ($40.6 billion) and the KPMG/University of Sydney survey ($51.8 billion), which has been published for ten years.

The ANU series focuses on the actual source country of investment and realised date of the investment unlike other measures which variously record approvals, country from which the money flowed, and contracted investment.

Nevertheless, the key points about growing private investment, quite small flows into rural Australia, diversification from mining, and growing numbers of smaller deals have been apparent in the KPMG/Sydney University series. The new database should ensure these points get more recognition in the policy making debate.

Head to head on trade

The tenth anniversary of the global financial crisis, with its undercurrent of uncertainty about the capacity for a new round of globalised economic policy, has unleashed an interesting showdown over trade policy.

Duelling new studies from the United Nations Committee on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the Bretton Woods trinity of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organisation both claim the right strategy for resisting isolationism.

But their very different solutions go a long way to explaining how the Labor Opposition can sustain such an intractable, perhaps unresolvable struggle over the frontier elements of the resized Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal.

Here’s UNCTAD’s new Trade and Development Report:

There is no doubt that the new protectionist tide, together with the declining spirit of international cooperation, poses significant challenges for governments around the world... Resisting isolationism effectively requires recognizing that many of the rules adopted to promote free trade have failed to move the system in a more inclusive, participatory, and development-friendly direction.

To which the trinity reply in their Reinvigorating Trade and Inclusive Growth paper:

Today’s fast-changing global trade landscape clearly requires a parallel change in global trade governance if multilateral trade liberalisation is to remain an engine of inclusive global growth. In the end, the WTO represents no more or less than the willingness of its members to cooperate – and to recognise that their national economic interests are increasingly bound up with their collective economic interests.

This is an old argument in some ways, but the tone of documents is revealing about contemporary times.

The UNCTAD authors seem to feel they occupy the moral high ground and can engage with the current anti-trade political zeitgeist. The trinity authors are more defensive and anxious to present new coalition of the willing-style liberalisation approaches in sectors (eg: Information Technology Agreement) and regions (TPP) as part of long-established post-Bretton Woods practice rather than a sign of failure.

Investment optimism

In the days of high import barriers, investment and trade were sometimes seen as alternatives with countries touting for foreign direct investment (FDI) behind their protective walls. The IMF/World Bank/WTO report has interesting data on how this thinking has changed.

Sales by FDI affiliates of US $38 trillion a year now exceed global goods and services exports at $21 trillion and exports by those affiliates account for one third of global exports. FDI is now seen as complementary to trade particularly through the creation of global supply chains.

As a result of the narrowing of the North-South divisions over FDI with the rise of emerging market investors, the study sees some scope for more global agreement over FDI rules amid the uncertainties about trade liberalisation.

Red metal

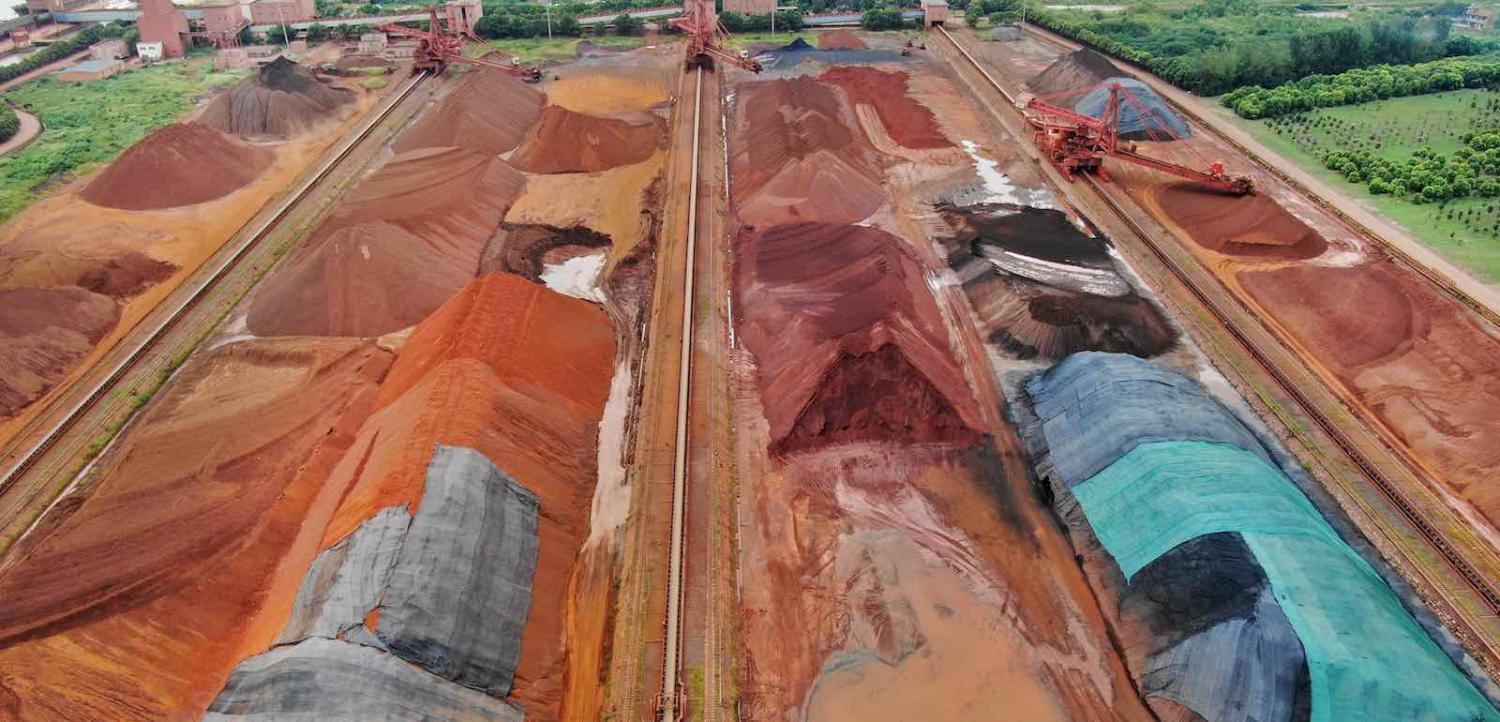

Mining company BHP has an obvious vested interest in selling resources into China’s Belt and Road Initiative ecosystem. But its bottom up analysis of how the BRI is travelling still offers a more disciplined insight into this amorphous development program than both the more hawkish views from the security establishment and bullish commentary from parts of the business sector.

In its latest analysis the company is sticking with the valuation of $1.3 trillion for genuine greenfields BRI projects over the next decade that it first used a year ago. This is a contrast to the media reports of numbers as high as $8 trillion over an unspecified time frame.

BHP is also emphasising the amount of power station construction occurring under the framework of the BRI in contrast to the more common media and political focus on transport, especially high-speed rail.

This has prompted BHP to forecast that BRI projects could push the demand for copper – known as the red metal – up 7% on what was needed last year which could be a significant fillip for the copper price.

While that might explain BHP’s continued optimism about the progress of the BRI, it has acknowledged the growing concerns about excessive debt burdens and the way new governments like Malaysia’s are reviewing BRI contracts.

Nevertheless, the company makes two points which suggest the BRI has some way to go. First it says China is developing the statecraft to manage the debt and governance risks associated with the BRI. And second it says the power projects in the BRI program will likely have a transformative impact on the development of other industries in BRI countries once they have the power supplies to fuel those industries.