As 2019 winds up, Lowy Institute staff and Interpreter contributors offer their favourite books, articles, films, or TV programs this year.

There are perks to being unfashionably behind the cultural curve. By letting new shows, books and tech percolate in the court of public opinion for a few years, it becomes easier to separate enduring favourites and cult classics from the chaff. One great Netflix show that has been marinading in our morally fevered times for two years is the Weimar-era German detective drama Babylon Berlin.

Whatever our anxiety about current levels of social dislocation and great power intrigue, it is worth reminding ourselves that previous generations had it worse.

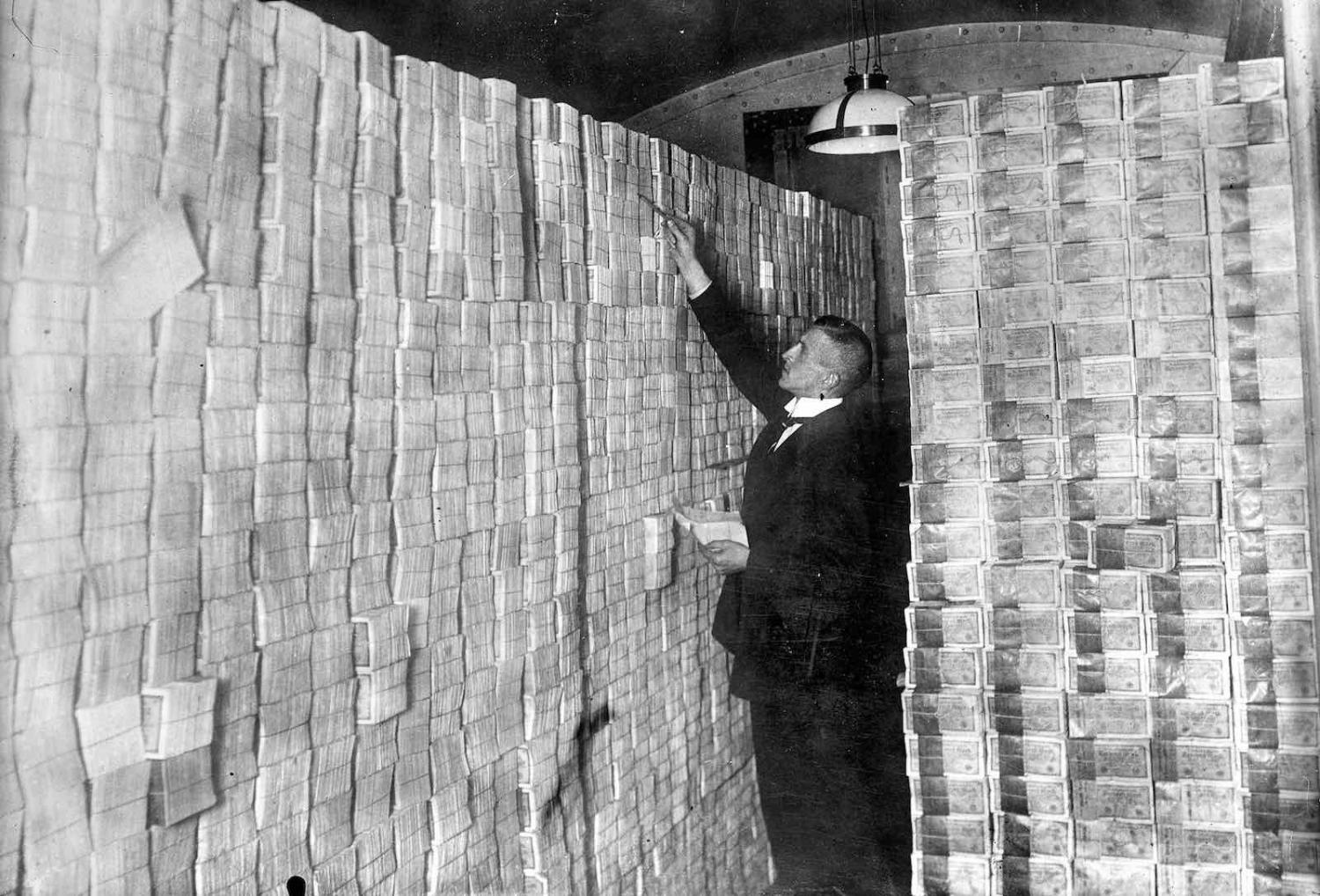

It is a well-crafted story that follows Gereon Rath (Volker Bruch), a police inspector from Cologne, and his sidekick, Charlotte Ritter (Liv Lisa Fries), a flapper from the slums, through a tumbling interwar society. But the true star of the show is glitzy and gritty Berlin. Set in Spring of 1929, in the midst of hyperinflation and just before the Wall Street crash, we are presented with an exultantly dark city that is at the centre of it all and yet teetering on the edge.

The night clubs of the jazz age are in full swing, imbuing the series with an excellent soundtrack. The Weimar Republic’s fragile democracy is beset by all sorts of extremes – from the ultranationalist far right to the Trotskyist far left. The Nazis are still dismissed as a fringe group. But we all know where this – and Germany – is heading. And that is the point.

The mystery is in the beginning not the ending. How do societies start to come apart at the seams?

Babylon Berlin successfully taps into our own contemporary malaise. The vertigo years of the first half of the 20th century have become a source of both entertainment and grim fascination. Partly it is therapeutic. Whatever our anxiety about current levels of social dislocation and great power intrigue, it is worth reminding ourselves that previous generations had it worse.

Partly it is that Babylon Berlin reminds us of the cyclical nature of history. As the saying goes, history doesn’t repeat itself but it does often rhyme. Our lives are prosperous and comparatively secure but, in the Trumpian post-truth age, we can relate to Gereon and Charlotte unpicking the narratives and counter-narratives eating away at the fragile centre ground.

The trouble today is that even the lessons of 20th century history can be fiercely politicised and deployed to suggest a pre-determined outcome. This year will be remembered for the thunder bolt that was Liberal MP Andrew Hastie’s op-ed in which he compared Australia’s China policy to the failure of the French to contain German expansionism in 1940. I would argue that falsely equates guarded diplomacy with strategic apathy.

Looking back with blinkers on is always risky. Take Brexit, a project fuelled by post-imperial delusions of grandeur. Ironically “Getting Brexit Done” may be the very thing that ends up dismantling even the original rump of the British empire – the one founded on the 1707 Acts of Union. Scotland voted as emphatically to remain part of the European Union as England did to leave it. If Brexit precipitates a Scexit that will be the end of the British state.

Better then to look to history to critically assess our preconceptions. As Prime Minister Boris Johnson gets ready for his first Christmas in Downing Street, he may well want to tuck into Thunder at Twilight: Vienna, 1913-1914 by Frederic Morton – a vivid portrait of the magnificent Hapsburg capital on the brink of losing its own centuries-old union of crowns.

The only certain parallel with the first half of the last century is pervasive uncertainty. We are living through our own pregnant pause. As old certainties give way, what replaces it is anyone’s guess.

The ghosts of republics and empires past wish you a very merry Christmas.