Pizza, kiwi, traffic light, Jamaica, Kenya or Germany?

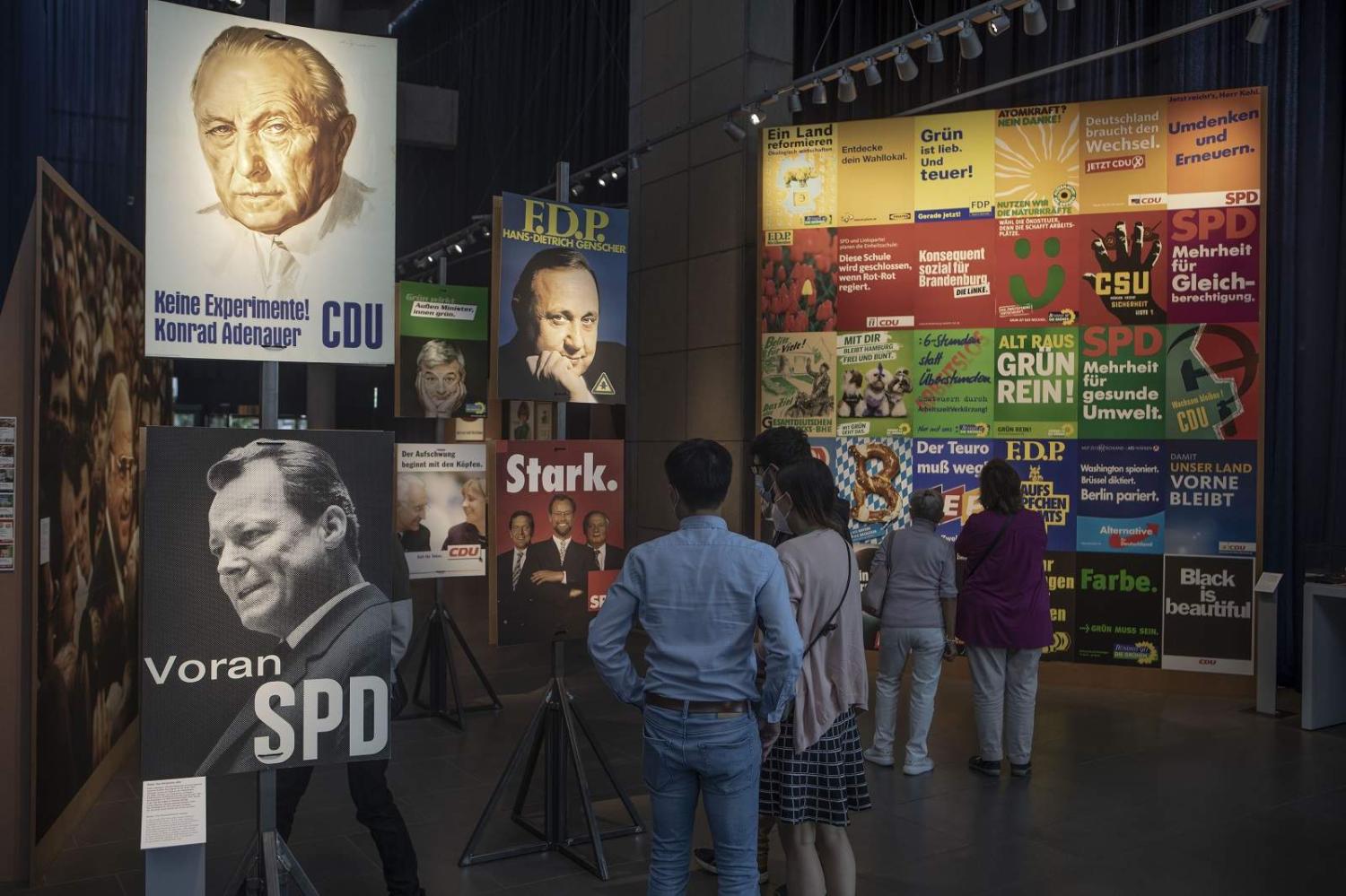

This curious spectrum of possibilities currently tantalises and torments German minds. Based on the trademark colours of the country’s mainstay political parties, it refers to the bewildering constellation of potential coalitions on offer after next month’s federal election. With the vote share of the old major parties seemingly on a permanent decline, and voting patterns more variable than ever, this is shaping up to be the most unpredictable election in many years.

The colour constellations matter. The next German government – and its leader – will ultimately be decided behind closed doors. Once the polls close at 6pm on 26 September, battles for power will be fought out in gruelling marathons of back-scratching, back-stabbing, poker faces and shady deals. It may be months until the participants finally re-emerge into the daylight. What does this mean for the three individuals running to replace Angela Merkel as German Chancellor – the conservative Armin Laschet, Olaf Scholz of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and the Greens’ Annalena Baerbock? What might we expect from Europe’s most consequential vote of 2021?

First, the likelihoods.

For the first time since the infancy of the Federal Republic in the 1950s, a three-party government looms.

Likelihood number one: Despite the poor showing of Laschet, the unmistakable scent of disunity (much of it emanating from Laschet’s vanquished rival, Markus Söder), and the historic lows at which it is polling, the conservative Union is very likely to remain the largest party in the Bundestag. Still, this is cold comfort for Laschet: it is by no means a given that the election “winner” will have any mandate to form and lead the new government.

Likelihood two: the parties of the far left (Die Linke) and far right (the Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD) will not feature in the coalition talks. There is, to be sure, a remote possibility of Die Linke featuring in a left-wing alliance. But this would be a product of necessity, not will: the Greens have little desire to work with the erratic socialists, the SPD even less.

And that’s it. Everything else is up in the air. So, what options does that leave us with?

Hope is now fading for what used to be considered the election’s most likely outcome: a Laschet-led venture between the two largest parties, the Union (whose colour is black) and the Greens. This is known, blandly, as a “Black-Green” coalition, though the relationship between the two parties is sometimes dubbed the “Pizza Connection” by the German media, in honour of the legendary sounding-out discussions between young MPs of both parties that took place at a Bonn pizza restaurant in the 1990s. (The Green-led variant, logically enough, is known as a “Kiwi” coalition.) But based on current polling, the combined results of the Union and the Greens fall a fair way short of a majority. This might change, of course, but the current trend is downwards, not upwards. Hence, for the first time since the infancy of the Federal Republic in the 1950s, a three-party government looms.

Lacking a majority of their own, the Union and the Greens might seek to supplement their partnership with the business-friendly Free Democrats (FDP). By virtue of the FDP’s yellow ornamentation, this combination is known as a “Jamaica” coalition, after the colours of that country's flag. For his part, Laschet has made clear his preference for working with the FDP, his current coalition partner in the federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia. And the FDP’s leader, Christian Lindner, is eager to reciprocate. The Greens’ position is more complex: the coal-friendly Laschet and the state-shrinking Lindner hardly furnish the most propitious environment in which to produce ambitious, generation-defining climate policies. The Greens might instead find it more hospitable to enter talks with the Social Democrats (SPD).

Indeed, a so-called “Traffic Light” coalition of the Greens, SPD (red) and FDP (yellow) has long been on the cards, and remains the only credible path to the Chancellery for Annalena Baerbock. For the left-wing SPD and Greens, this would be relatively straightforward – the two parties governed Germany together between 1998 and 2005. The stumbling block is the FDP: Lindner has long harboured reservations about propping up a Green Chancellor.

An alternative is a “Traffic Light” coalition led by the SPD. In theory at least, Lindner would be far more willing to throw his weight behind the centrist Olaf Scholz – an arrangement which the Greens would be unlikely to reject on principle. Scholz – Merkel’s Finance Minister and Vice-Chancellor – has long believed that a result of just over 20 per cent (not so long ago an unequivocal catastrophe for his once-proud SPD) could hand him the keys to the Chancellery. Ever since being nominated as the SPD’s Chancellor candidate back in August 2020, his strategy has been simple: exude competence. It might be beginning to work. Scholz’ personal ratings are increasing as the campaign unfolds. His popularity now easily exceeds that of Baerbock and Laschet, both of whom have hampered their campaigns with careless mistakes. Despite the seemingly irreparable fissures that subsist within the SPD itself, it is completely foreseeable that a late surge – even one comprised of a small handful of percentage points – would catapult the party ahead of the Greens and set up Scholz as Angela Merkel’s successor.

Coalition negotiations are exhausting tussles of give-and-take, which do not always yield the optimal results.

Are there other options? Some in the FDP and CDU have floated the idea of a so-called Germany Coalition, comprised of the Union (black), SPD (red) and FDP (yellow). But the idea is probably a non-starter. The SPD has ripped itself apart over the past eight years on precisely the matter of serving as the CDU’s junior partner. There is zero appetite among Social Democrats to subject themselves to another four years of political masochism. The same goes for a “Kenya” coalition with the Union and the Greens, so-named after the black, red and green stripes of the Kenyan flag.

The arithmetic might be further unbalanced by the ascension of the Freie Wähler (Free Voters): a conservative-ish alliance of regional independents who are closing in on the five per cent nationwide minimum any party requires to enter the Bundestag. Their leader, Hubert Aiwanger – the Deputy Premier and Finance Minister of Bavaria – has dallied with vaccine scepticism in a cynical ploy to put his party on the national map. The SPD and Greens would be unlikely to work with them. The Union and the FDP, however, have not ruled it out.

Coalition negotiations are exhausting tussles of give-and-take, which do not always yield the optimal results. Back in 2017, months of futile wrangling ultimately landed Germany with an unhappy and unpopular marriage between the Union and the SPD. This time around, the prospect is even more daunting: a broader spread of votes across the parties means a wider spectrum of coalition possibilities. And, of course, the negotiations will take place without the experience and authority of Angela Merkel. Indeed, the Chancellor’s absence already seems to have generated a degree of political disorientation: given how much is at stake in this election, the efforts of all three major parties so far have been strikingly insipid and unambitious. After 16 years of Merkel’s steady hand, it seems, Germany has completely forgotten what a different Chancellor might look like. It has six weeks to remind itself.