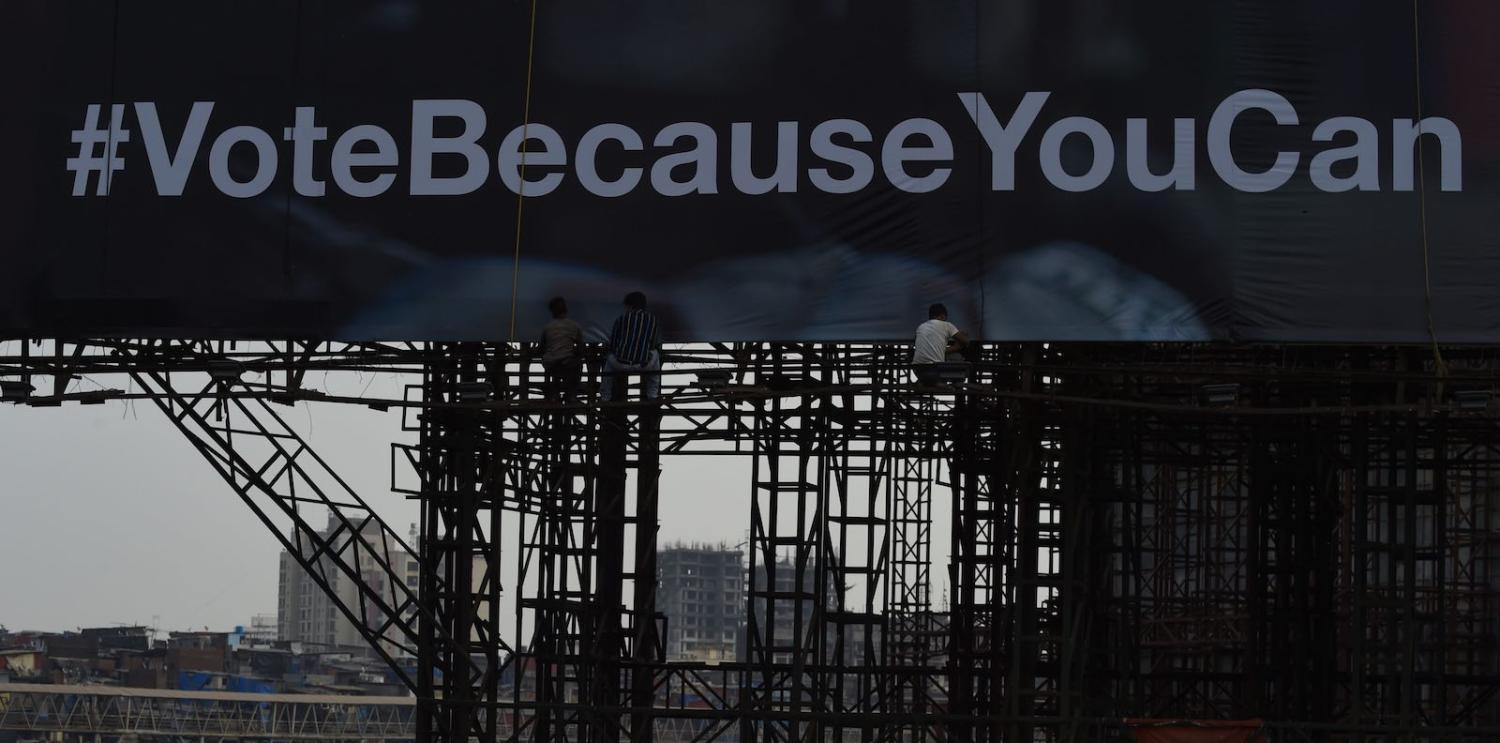

At the end of a visit to India in the middle of a long and heated election campaign, the conversation with some young thinktank staff captured the country’s appetite for its democracy.

After mentioning I had been making comparisons with the parallel Indonesian election, they suddenly besieged me with questions about how more than 300 election staff could have died there from overwork.

“Something like that could never happen here,” one declared confidently and asked why there hadn’t been better organisation of the process – perhaps like India with seven phases of voting and electronic voting machines.

There is a rising sense of hubris that the world’s fastest growing large economy has an embedded democratic culture that deserves more respect abroad.

With 2700 registered parties, 900 million voters, 3000 social castes, 300 TV news channels and live insurgencies from the Islamist to Marxist varieties, India’s election can be as confounding as it looks. But it also remarkably well organised.

And there is a rising sense of hubris that the world’s fastest growing large economy has an embedded democratic culture that deserves more respect abroad when things are not going so well in the bastions of democracy in London and Washington.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) likes to bask in a doubling of its membership to 110 million in the past five years to symbolically overtake the Chinese Communist Party and about four times larger than the rival Indian National Congress party.

A former military officer argues all India’s South Asian neighbours now regularly change governments at elections after the example of India until you get to the Chinese border. And what’s more, that is a better record than Southeast Asia can boast.

Pollster Yashwant Deshmukh says ground zero for the resilient Indian voter was 1977 when opposition leaders were detained but millions of illiterate, poor people queued for hours to kick a shocked Indira Gandhi out of office after two years of overconfident emergency rule.

And Ruchir Sharma writes in his new book Democracy on the Road:

While in some opinion polls Indians express a growing desire for a strong leader, unshackled from an often-gridlocked parliament, the electoral reality is that the country rebels against domineering party bosses.

This election now seems to come down to whether Modi is indeed going to be seen as just another party boss or someone reflecting the idea that India is becoming a more singular political entity rather than the usual kaleidoscope of regional, caste and religious parties.

Former political commentator Ashok Malik, now in the president’s office, says rapid economic growth with a mobile workforce, urbanisation and new communications technology is changing the way Indians look at both local and national elections. He says:

Technology is helping unite Indians across geography about how they think about issues from festivals to terrorism.

But creating a greater sense of electoral nationalism out of these undeniable social, economic and technological forces is not so straightforward in a country where national purpose has long been about avoiding outbreaks of communal violence and the BJP’s rise as a modern national party is built on a bedrock of Hindu nationalist groups.

Modi’s image as the purveyor of dreams about a new economy to millions of aspirational young Indians back in 2014 (when he also promised a still non-existent trade agreement with Australia in a year), has also changed significantly.

The addition of the word chowkidar (watchman) to his twitter handle reflects a decisive shift to national security concerns over economic reform dreams at this election and looks more like the strategy of an old party boss than a new nation builder.

Nevertheless, BJP foreign affairs chief Vijay Chauthaiwale argues that the party will win due to Modi’s rising stature as a genuine national leader complimented by the creation of a national political machine to suit the times in contrast to the other dynasty, caste and regional based parties.

In an interesting explanation of the strategy he says:

Last time the people gave us a mandate on the basis of hope that Mr Modi will deliver and now we are asking for a new mandate on the basis of their aspirations… And it is an election of aspirational voters.

The opposition Nehru-Gandhi family-led Congress Party faces a dilemma regaining ground at this election after a disastrous performance in 2014 because it is trapped between running as the once dominant party of government and the new reality of now being one of several opposition parties.

But Congress communications chief Randeep Surjiwala rejects the idea that the country’s oldest party is struggling to find its way as one of many opposition parties while the BJP responds to a new more national electorate, saying: “Our ideology is based on collaboration.”

He says the BJP has used “isolation, division and diversion as tools of state” to undermine the ability of India’s non-Hindu nationalist religious and social groups to “walk alongside” the majority.

“It’s not about right or left or centre. It’s about preserving India’s civilisational values. That’s the broad difference of ideology at this election,” Surjiwala says of the debate about a new India.

CNN-News 18 political editor Marya Shakil has a more pragmatic take on whether this is an election for a new more electorally unified nation or not: “People voting for him (Modi) are voting for the man and people not voting for him are voting for the party.”

But still, it might be argued, an election over two different interpretations of modern nationhood is a lot more edifying than the battle in Australia about whether negative gearing changes are going to hurt house prices.

Greg Earl visited India as part of an international observer group sponsored by the India Foundation with assistance from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.