In the coming months, Japan will be in a position to enact its long-announced plan to release contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the Pacific Ocean. Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who will make the final decision on whether to go ahead with the plan, will have to balance the fact that the tanks currently being used to store the water will reach their capacity in early 2024 against the environmental and political risks that the plan to release the water presents. How he ultimately does this is likely to have significant ramifications not only for his own domestic standing, but for Japan’s international reputation as well.

The challenge stems from the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami, which caused a meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear reactor located on Japan’s Pacific coast. Since that time, the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO), has had to pump in water to cool the melted fuel and fuel debris. Once the water comes in contact with the radioactive materials, it becomes radioactive itself.

TEPCO has been using a process known as Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) to remove most of the radioactive elements in the water, but the technology is not able to remove from the water the low levels of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. The treated-but-still-contaminated water is currently being stored at the power plant in specially designed tanks. Although TEPCO has constructed enough tanks to store more than 1.3 million cubic metres of contaminated water, it expects that the tanks will reach their capacity early next year.

In 2021, the Japanese government published a plan to slowly release the contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean. According to the government, the water that will be released will present a minimal risk to humans and the environment, with the level of radioactivity falling far below established safety levels. The final piece of an undersea tunnel that will be used to release the water was recently installed, leaving only final safety checks and official approvals before the water will be able to begin to flow.

Shortly after Japan announced its plans in 2021, it requested technical assistance from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), with the IAEA Director General setting up a task force to provide a science-based safety review of Japan’s plan. The task force is expected to release a comprehensive draft report in the near future.

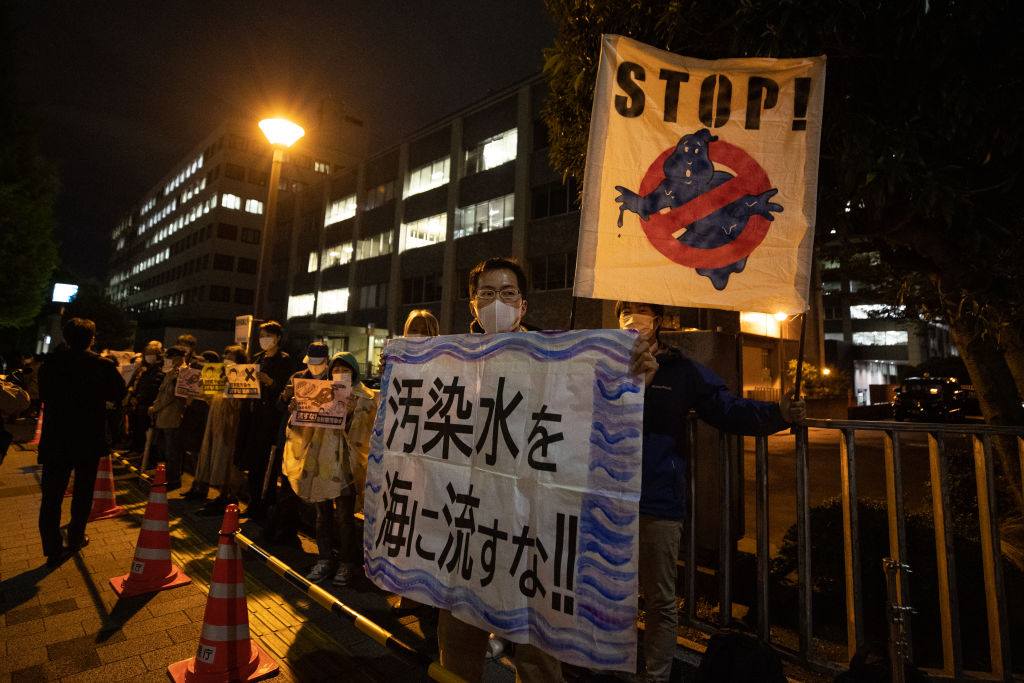

When the government first announced its plan, it was met with significant concern – if not outrage – from a variety of groups both inside and outside of Japan. Protests against the plan came from China, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Pacific Island countries that view the ocean as part of their identity.

Now, two years later, there is still robust opposition from many of these same places. Japan’s fishing industry recently reiterated its opposition to the plan, China is accusing Japan of using the Pacific Ocean as its “sewer for discharging its nuclear contaminated water”, and the Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum has called for continued discussion and study before the water is released. Australian Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy recently echoed the Pacific Islands Forum’s position, explaining Australia’s expectation that “any discharge of treated water by Japan will be fully informed through scientific assessments” and hope “that everyone just keeps talking”.

However, as a result of its diplomatic and educational efforts, Japan has begun to win over some of the objectors. The leaders of the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of Palau now say they have no objection to the release of the contaminated water. Additionally, a South Korean delegation recently visited the Fukushima site to collect additional data, showing a willingness to revise its existing opposition.

Assuming that the IAEA’s report agrees with Japan’s contention that the release of the contaminated water presents only a minimal risk to the environment and that Kishida decides to move forward with the plan, the question the prime minister will face is how to handle the political difficulties he is likely to encounter.

Within Japan, Kishida’s approval ratings have recently declined over unpopular domestic policies, raising questions of whether he will call a snap election to seek a fresh mandate. In this context, approving the release of the contaminated water before ameliorating domestic opposition from the fishing industry and others may present a meaningful threat to his own political future.

At the international level, approving the release plan risks derailing the recent rapprochement between Japan and South Korea, whose relationship has long been tense for historical reasons. It could also undermine decades of effort that Japan has put into building its status as a trusted partner for the Pacific Island countries, as well as its desire to create a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific”.

Given the fact that the storage tanks at the power plant will soon reach capacity, the inescapable reality is that action will need to be taken. The decision and resulting impact will ultimately determine whether the action is as severe as the initial meltdown.