It would almost seem nothing could further divide politics and society in the Philippines – and then the coronavirus arrived. Only three cases have been confirmed in the country, but rampant fears and unchecked anxieties are playing into the existing division.

The first half of President Rodrigo Duterte’s term consistently forced that gap wider, with disputes over the deadly war on drugs, attacks on the media, the judiciary, and more recently with the collapse in US relations. A public health crisis joins an already crowded set of headlines.

The Philippines is somewhat of an outlier in the region in its rhetoric towards China. While Duterte has stopped short of a “solidarity” visit to Beijing, unlike Cambodian counterpart Hun Sen, his government faces repeated accusations of courting goodwill with China at the expense of Filipinos.

Critics say the government had dragged its feet in issuing a travel ban on China and its territories in the wake of the virus outbreak, putting it out of step with much of Southeast Asia. While the utility of such bans is controversial, the optics gave the “yellows”, as the anti-Duterte opposition are known, fuel to the argument that the President is ceding sovereignty to China, first in the South China Sea, and now in public health.

It’s a claim that has followed Duterte since the early days of his leadership. Taking office in 2016 just weeks before an international tribunal ruling in favour of the Philippines’ claim to disputed waters in the South China Sea, the country’s official stance towards Beijing softened, prompting protest from left-leaning activists. A preoccupation with securing investment has high-profile critics wondering aloud if infrastructure projects could be “trojan horses with dire consequences for the Philippines”.

Now, by tying its initially slow response to the coronavirus to investment, the Duterte administration is struggling to establish credibility in a fight against anti-Chinese racism.

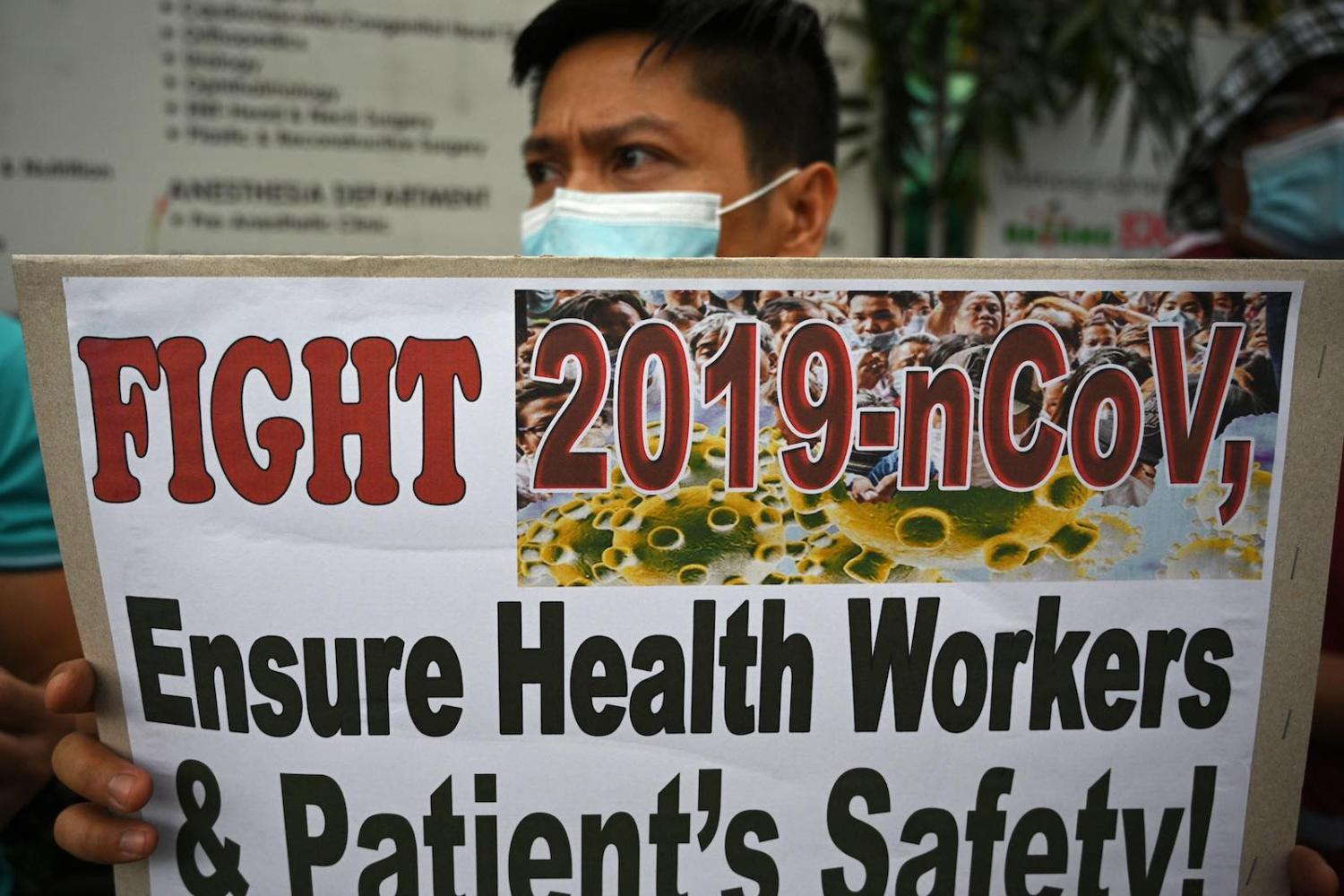

Authorities ordered tighter screening of passengers arriving in the country from Hubei province in early January but struggled to maintain control on information and public fears as the crisis escalated in China and then across Southeast Asia.

A slow down on flights between the Philippines and Wuhan temporarily allayed fears, but as the first known case in the Philippines was confirmed 30 January, public fears spiked. The 38-year-old Chinese national is believed to have contracted the virus in Wuhan, his home city. Just days later, a 44-year-old Chinese national died in a Manila hospital – the first coronavirus related death outside of China.

An order in late January to repatriate Filipinos based in China helped to stem criticism of the Duterte administration momentarily. Planes sent from Manila to bring nationals home would be loaded with donations of supplies for Hubei province’s hospital, Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teddy Locsin Jr. wrote in a typically expletive-laden Tweet: “China helps us we help China”.

When our plane goes to Hubei to evacuate Filipinos who want to leave plane will be loaded with food items, masks if we find any, everything. And DFA will pay for it because I don't give a shit about audit procedures in this case. China helps us we help China. I have spoken. https://t.co/bZL2jwGKAh

— Teddy Locsin Jr. (@teddyboylocsin) February 7, 2020

Less kind words have been reserved for left wing critics. In an almost invert of domestic discourse everywhere, the hard right in the Philippines has consistently accused the left of “Sinophobia” in its demands to close borders. Conservative columnist for the Manila Times, Rigoberto D. Tiglao, laid out the argument in a column last week, dismissing critics as “rabidly anti-Duterte and anti-Marcos and racist.

And Tiglao has a point. Reports from across the world of heightened prejudice against the Chinese diaspora are a foolish and dispiriting response to the virus outbreak. Yet even so, the credibility of those lawmakers, journalists and conservative activists who otherwise offer fulsome support of Duterte’s other domestic policies – including the President’s well-known pattern of invective – seems stretched when it comes to racism.

Chinese-Filipinos are the country’s largest ethnic minority, and are well-represented in the upper echelons of the business and political community. Still, the long history has not shielded them from fears.

Indeed, Duterte’s own comments muddy the waters. He has linked anti-racist comments with the importance of China as a trade partner. “China has been kind to us, we can only also show the same favour to them. Stop this xenophobia thing,” he said shortly after the death of a Chinese national in early February. By making coronavirus and criticisms about the public health response an identity issue, it appears Duterte and his aligned supporters seeking to wedge the left by its own language and values. That criticism should be heard — but it’s the ethnic-Chinese minority who should be listened to.

Chinese-Filipinos are the country’s largest ethnic minority, and are well-represented in the upper echelons of the business and political community. Still, the long history has not shielded the community from fears. Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown and the oldest in the world, briefly became a hub for rumoured cases prior to the first confirmation.

Col Tiu, an ethnically-Chinese Filipina, wrote at length for Rappler about the stress and ostracisation the community is feeling. “I have never seen the Chinese be more sorry just for being Chinese. I have also never felt more ashamed for having a Chinese family name,” she said, noting cases of discrimination such as Chinese students singled out for self-quarantine by schools.

The last word should go to Teresita Ang See, a leader with the Chinese-Filipino community group Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran. She is convinced that the associated racism is more detrimental to the country than a public health crisis. As she puts it: “The ‘you vs. us’ attitude, finger-pointing, and racism are deadlier and cause more permanent damage than the virus we are now fighting collectively as one humanity.”