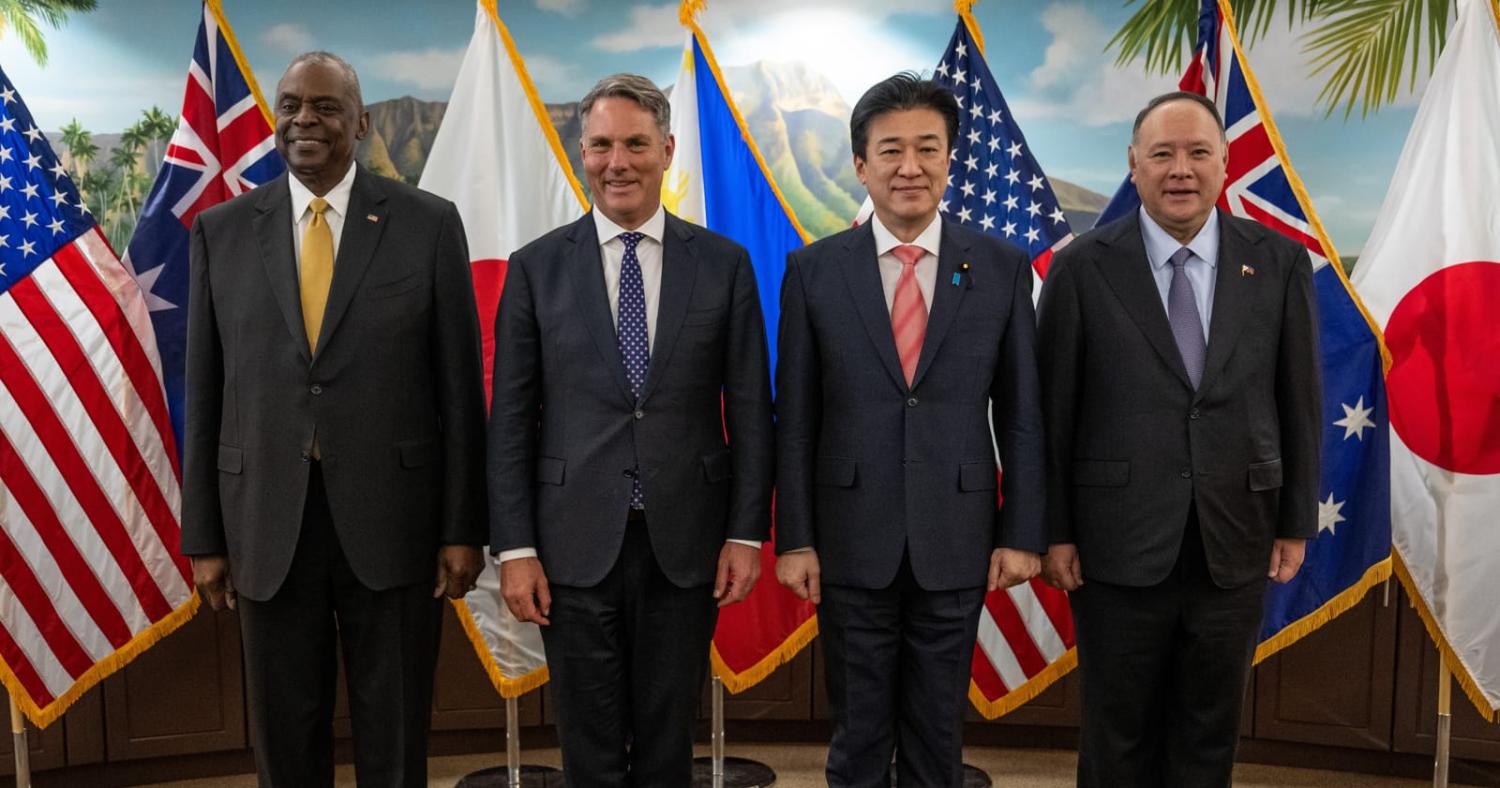

A few days ago, US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin hosted his counterparts from three allied nations – Japan, Australia and, crucially, the Philippines – in Hawaii, also home to the headquarters of the US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM). The meeting marked the second gathering of the four defence ministers, who underscored their commitment to “advance a shared vision for a free, open, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific”.

The first gathering was on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore last year. Although the four defence leaders didn’t directly point their fingers at China, the new quadrilateral grouping is primarily about checking the Asian superpower’s worst instincts. In fact, the four defence ministers met not long after a historic quadrilateral joint patrol in the South China Sea amid Beijing’s increasingly aggressive harassment of Philippine patrols and resupply missions in the disputed waters.

The latest meeting coincided with the Philippine–US Balikatan exercises, –of which Australia and Japan are observer nations – focusing on threats posed by China to both Taiwan and across the South China Sea. Accordingly, Austin hailed this quadrilateral gathering as an important step in “chart[ing] an ambitious course” towards a rules-based order in Asia and, crucially, emphasised the significance of “deterrence” in upholding peace and stability in the region.

The crystallisation of the new quadrilateral grouping, dubbed the “Squad”, is a testament to the growing importance of “minilateral” cooperation in the Indo-Pacific as well as the steady yet dramatic shift in the Philippines’ strategic outlook.

It’s hard to understate the emergence of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, better known as the Quad, among India, Australia, Japan and the United States. The grouping has illustrated the practicability of what journalist Moises Naim termed “minilateralism”, flexible, ad-hoc, issue-specific cooperation with a narrow yet consequential range of threats.

But recent developments have exposed the limits and inherent fault lines within the original Quad.

Shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I asked India’s outspoken chief diplomat during the Munich Security Conference whether the Quad is the new “Asian NATO”. In response, a somewhat pugnacious Subrahmanyam Jaishankar urged me not to “slip into that lazy analogy” and made it clear that the Quad “doesn't have a treaty, a structure, a secretariat” since it was primarily about “four countries who have common interests, common values, [a] great deal of comfort, who happen to be located in the four corners of the Indo-Pacific”.

Jaishankar rightly reminded the world that India doesn’t seek any treaty alliances or entanglements with Western powers. But the true relevance of his intervention came to light over the succeeding months, when India refused to condemn Russia’s brazen invasion of a sovereign state in consecutive United Nations resolutions and, crucially, insisted on maintaining robust trade and defence ties with Moscow. If anything, India, in clear defiance of Western sanctions, pressed ahead with the acquisition of Russian-made S-400 air defence missiles and, even more concerningly, became the top importer of Russian oil on heavily-discounted terms.

Whenever pressed on the issue, Jaishankar has struck back at Western nations by publicly accusing them of “hypocrisy” and presenting India as a Global South leader resisting neo-colonial pressure. Growing concerns over India’s alleged political assassination plots against dissidents residing in the West have added a new layer of tension to the Quad grouping. Under its “multi-alignment” strategy, India’s primary interest is to pursue its own “great power” moment and push for a post-Western multipolar order.

Enter the Philippines, which, unlike India, has consistently backed UN resolutions condemning Russia’s actions, cancelled defence purchases and planned energy deals with Moscow, and openly embraced a US-led “integrated deterrence” strategy against China. Not to mention, the Southeast Asian nation is already a US treaty ally, enjoys a Status of Visiting Forces Agreement with Australia, and is negotiating a Reciprocal Access Agreement with Japan.

The new “Squad” is a natural outgrowth of a whole series of US-led minilateral initiatives with treaty allies, most notably the Australia–UK–US (AUKUS) and Japan–Philippines–US (JAPHUS) trilateral groupings.

Although bereft of India’s heft, the Philippines brings both moral clarity and strategic alignment to the new quadrilateral grouping. The Philippines is also in the midst of a massive US$35 billion military modernisation program, which aims to make the country a fully-fledged “middle power” with advanced naval and air force capabilities. .

Crucially, the Philippines’ geography, bordering both the South China Sea and Taiwan, makes it indispensable to any effective “constrainment” strategy against China. During this year’s Balikatan exercises, the Philippines conducted unprecedented drills – with the United States and other regional allies – that focused on potential armed conflict with China in either the South China Sea or Bashi Channel in Taiwan’s underbelly. The Philippines is also contemplating granting expanded access to the United States and partner nations in its northernmost provinces in anticipation of potential contingencies in nearby Taiwan.

As the “Squad” develops, it needs to institutionalise its promising partnership through regular joint patrols in the South China Sea and across Western Pacific, expanded intelligence-sharing and maritime security cooperation, and collective efforts to accelerate the Philippines’ military modernisation.

In the short term, however, the clear challenge is to deter China’s increasingly aggressive ‘grey zone’ tactics, which have led to the injury of Filipino naval officers in the South China Sea. Aside from reiterating its mutual defence treaty obligations to the Philippines, the Biden administration has to coordinate various diplomatic, economic and military countermeasures to address Chinese coercive behaviour in the disputed waters. In the meantime, the “Squad” sends a reminder to China that the Philippines is not alone – and that Beijing needs to reconsider its aggressive stance, lest it crystalise a de facto “Asian NATO”.