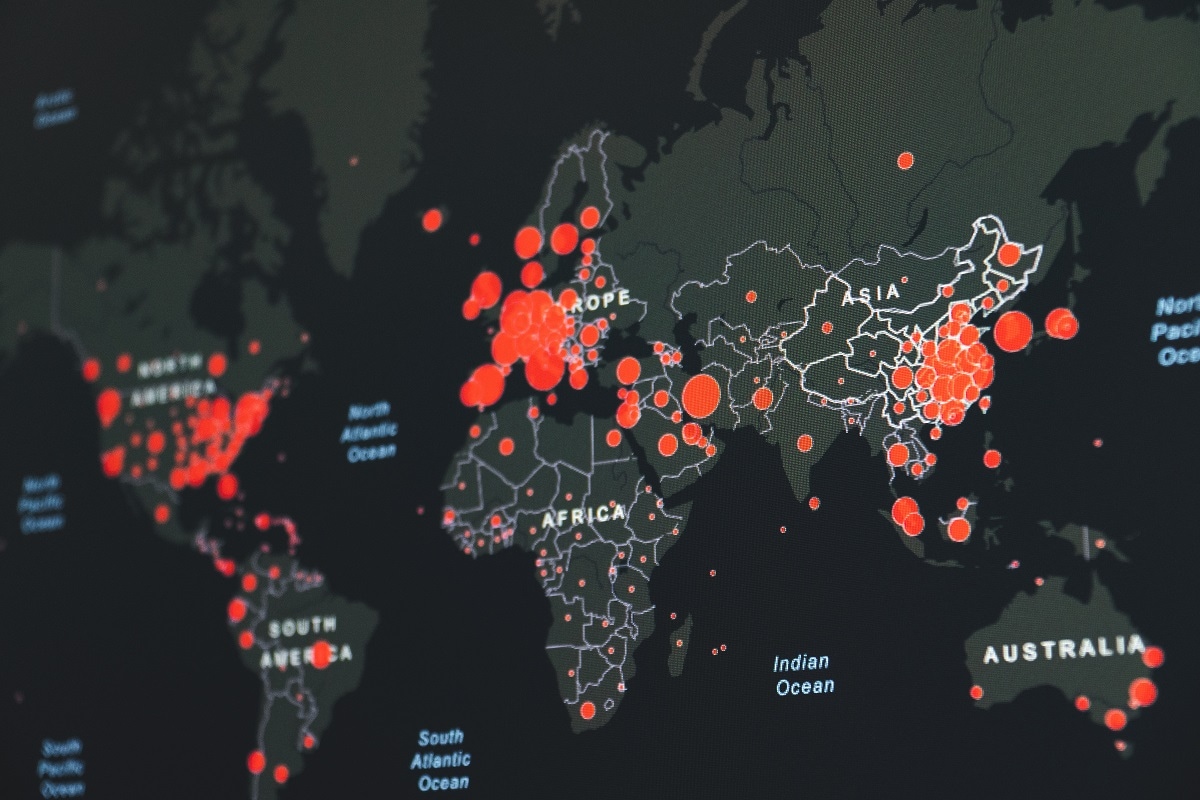

The Singapore Strait is experiencing a spike in maritime piracy attacks, with the incidence increasing from 12 attacks in 2019 to 38 in 2022, and an upwards trend continuing into 2023.

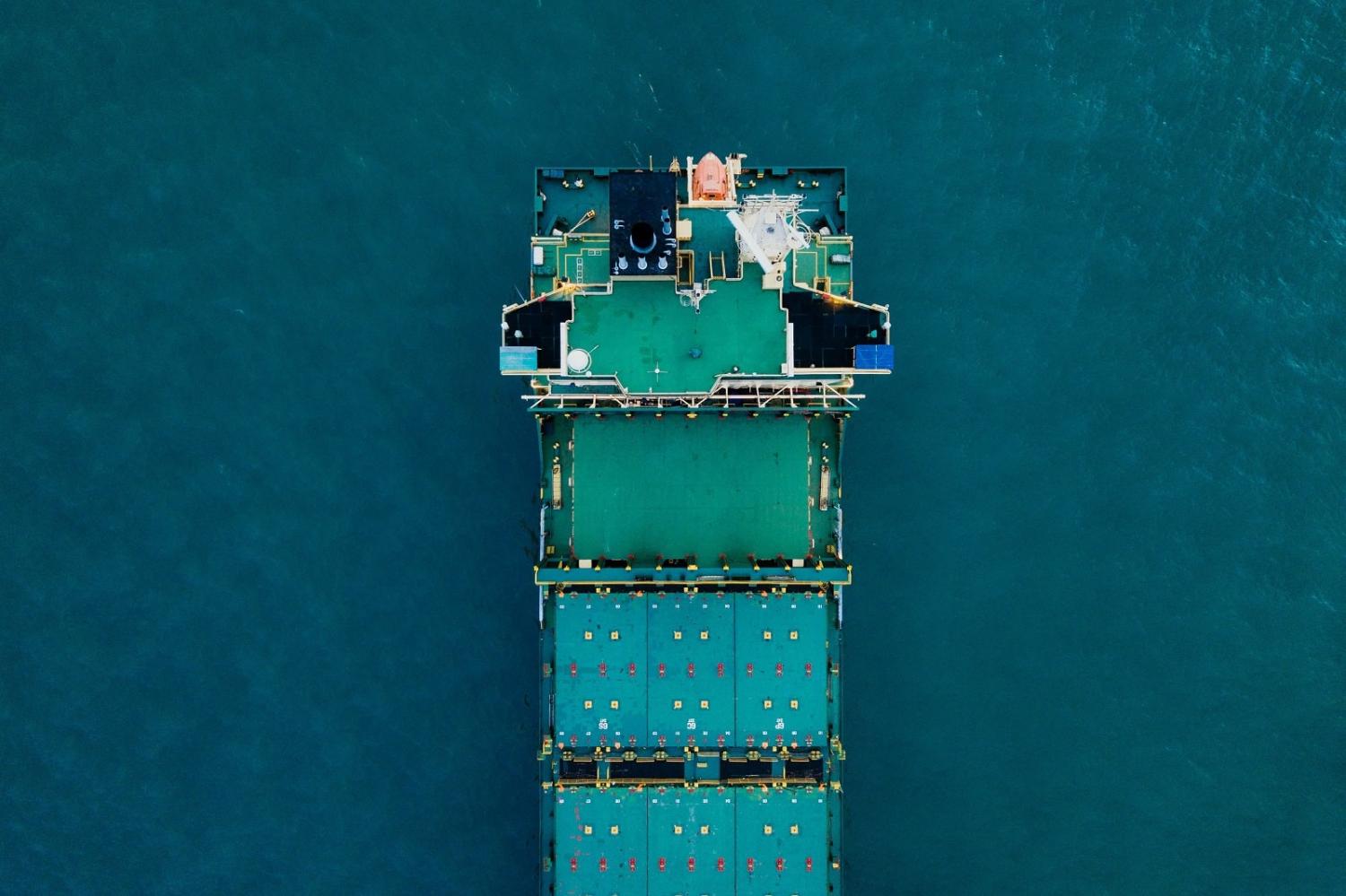

Southeast Asian waters are of geostrategic importance to global shipping routes, maritime trade, and networks of port hubs that are vital for state economics. The region’s archipelagic states, extensive coastlines, and congested chokepoints create ideal conditions for piracy.

What created the conditions for a surge in Singapore Strait piracy? Coinciding with the 2020–22 timeframe is of course the Covid-19 pandemic – a global health and economic crisis that triggered national restrictions affecting coastal and fishing communities in Southeast Asia. Further investigation into the link between the pandemic and increased piracy revealed heightened motivation to offend and decreased efforts to prevent attacks in known piracy hotspots.

Socio-economic pressures and poor economic conditions in coastal communities can motivate unemployed shipyard workers, seafarers and fishers into piracy. Similar to the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic included a shutdown of operations that caused a decrease in global trade and supply chain disruptions that led to Asia’s first regional economic contraction in decades. Among coastal communities, poverty, economic inequality, unemployment and commodity prices increased while households turned to crime, including piracy, to supplement their income.

Throughout the pandemic, the maritime sector was impacted by lockdowns, which increased financial vulnerability. The fishing sector experienced a decline in employment hours and decreased consumer demand. The economic welfare of fishers was damaged by decreased income opportunities due to fish market closures, including a decline in seafood exports by as much as 70 per cent during the early days of Covid-19. As such, approximately 2.7 million Indonesian fishers fell below the national poverty line.

Covid-19 also disrupted the operation of ports in Indonesia and Singapore, with governments adopting lockdown measures, travel restrictions and mandatory quarantine orders that reduced supply and restricted operations. Seafaring was particularly affected. The Seafarers Happiness Index for Q2 and Q3 of 2020 indicated that fatigue and financial woes impacted those both aboard vessels and ashore.

Why did the Singapore Strait experience a six-year high as a piracy hotspot in comparison to other parts of Southeast Asia, such as Indonesia? Our analysis found that the rise of piracy in the Singapore Strait can be attributed to three main causes.

First, institutional capacity was weakened throughout Covid-19 due to the reallocation of resources from maritime security to healthcare and social security. This resulted in regional navies, coast guards and other maritime law enforcement agencies responsible for maritime security and surveillance operating with decreased funding, hampering regional maritime security efforts. Singapore reduced its defence budget in 2020, noting a 2.4 per cent reallocation of defence funds in part to deal with the pandemic.

Second, the Singapore Strait has a decentralised maritime security framework, as it is composed of the territorial waters of Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia. The Singapore Strait’s maritime security architecture and surveillance, therefore, relies on cooperative mechanisms between the littoral states, which can result in sovereignty concerns and ambiguity over laws for the “right of hot pursuit”. Regime complexity in the governance of waters can result in regulatory gaps that hinder transnational approaches to combat piracy.

A final consideration is the geopolitical conditions that can result in the absence of capable guardianship. There was a decrease in maritime patrols in the Singapore Strait from December 2019, as the Indonesian navy was deployed to the South China Sea to advance Indonesia’s claim to the Natuna Sea against China’s assertions, creating an absence of maritime surveillance and increased opportunities for piracy in the Singapore Strait. Coastal surveillance was deprioritised as budget reallocations to combat Covid-19 resulted in decreased administrative capacity, causing weaknesses in law enforcement at sea.

Examining Southeast Asia’s maritime piracy spike during Covid-19 helps shed light on how the pandemic contributed to piracy trends. Lessons learned can usefully inform future industry disruptions, such as supporting the livelihoods of fishing industry workers and maintaining capable guardianship to prevent future piracy surges.

_________________________________________

For more on the subject, see: Dhiyaul Aulia Huda and Jade Lindley, (2023) ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on Maritime Piracy in the Singapore Strait: A Routine Activity Theory Analysis’, Blue Security.

This article is part of the ‘Blue Security’ project led by La Trobe Asia, University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, Griffith Asia Institute, UNSW Canberra and the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy and Defence Dialogue (AP4D). Views expressed are solely of its author/s and not representative of the Maritime Exchange, the Australian Government, or any collaboration partner country government.