This is the first post in a three-part series.

The current terrorist problem is, by most metrics, larger than ever.

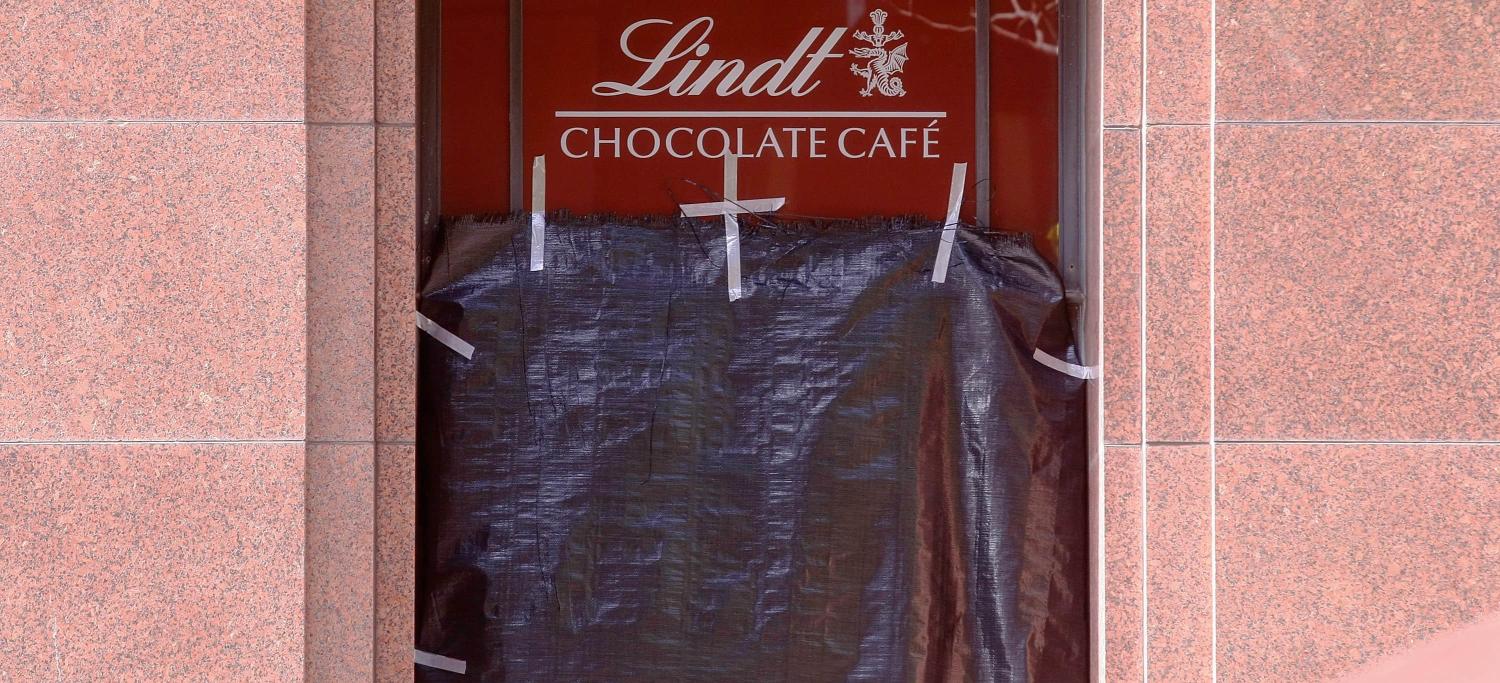

There have been four successful terrorist attacks in Australia since September 2014. Outside of Australia, terrorist attacks are occurring more frequently and killing greater numbers. While the large majority of these have taken place in just a handful of countries, in 2015 and 2016 there were multiple attacks in Europe; South and Southeast Asia; North, West and East Africa; and North America.

Yet the terrorist threat is more than just the attacks that actually transpire. The actions of counter-terrorism authorities have thwarted planned attacks and prevented other terrorist offences from taking place. As a result, arrests associated with disrupted attacks, attempted travel to terrorist hotspots and other terrorist offences have become a frequent occurrence.

Thousands of individuals are currently under investigation for potential terrorist activity. In Australia, ASIO estimates indicate that almost 200 Australians are actively supporting Islamic State, with a further 110 overseas fighting in the Middle East.

The escalation in terrorism-related activity means that counter-terrorism is both a higher priority for governments, and of greater concern to the general public. As a result, governments across the world are communicating more frequently about terrorism and counter-terrorism.

This communication takes many forms: formal press releases from government ministers and heads of departments or agencies; media interviews or broadcasts; updates relating to the arrest or prosecution of terrorist offenders; and physical actions such as an increase in security agency presence.

The focus and framing of these communications largely reflect how counter-terrorism is typically defined: activities designed to prevent or deter terrorist acts. Common examples include updates on improvements to a nation's counter-terrorism capability, legislative and criminal justice reform, additional security measures in specific locations, and (to a much lesser extent) longer-term prevention via a counter-radicalisation strategy.

In addition to prevent and deter, a third, critical element of counter-terrorism (missing from many counter-terrorism strategies post-9/11) is resilience: the ability of a system or society to absorb shocks caused by terrorism and reorganise while retaining its essential structure and identity.

In Australia, resilience has been central to counter-terrorism policy documents (if not actual counter-terrorism policy) since 2010. The counter-terrorism white paper 'Securing Australia, Protecting Our Community' listed resilience as one of the four key elements of the government's counter-terrorism strategy. The most recent Australian counter-terrorism strategy document, 2015’s 'Strengthening Our Resilience' made the centrality of resilience to the Australian counter-terrorism response even more explicit.

There are a number of different aspects to resilience in the counter-terrorism context. Yet within both strategy documents, resilience is framed in either a preventative context (protecting key infrastructure or helping society resist violent extremism) or a reactive context (ensuring an effective law enforcement or military response in the event of a terrorist attack).

What neither document adequately addressed was how the government could maintain and increase emotional resilience against the fear of future terrorist activity, regardless of whether this activity occurred.

In a climate where even the best efforts of intelligence and law enforcement agencies might be unable to prevent an attack, a counter-terrorism strategy needs to communicate more than the government response. It also needs to make the threat of terrorism less terrifying – not just reducing the threat but also reducing the fear associated with it.

A communication strategy that fails to place fear-reduction at its centre ignores what differentiates a terrorist act from many other forms of violence. It has a primary and secondary effect; a short-term immediate impact followed by a longer-term one that ripples across the public consciousness.

Placing too great a focus on the violent act may result in this secondary effect, even if the context is solely preventative and a violent act has not actually occurred. Fear increases even when terrorist attacks are being prevented.

Notwithstanding the recent increase in terrorist threat, in the Western world at least, fear of terrorism outstrips the likelihood of it occurring by some distance. In the Lowy Institute Poll 2015, fewer than one in four Australian adults said they felt very safe, the lowest recorded result in the eleven years of the Poll. Respondents identified the emergence of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and terrorist attacks on Australians overseas as the two greatest risks to Australia's security over the next ten years.

This problem is not unique to Australia. A Gallup survey in February 2016 found that international terrorism was ranked the most critical threat to the United States over the next decade. In June 2016, respondents to a Pew survey in nine of ten European countries identified Islamic State as the greatest threat facing their countries.

And yet, over the past three years, terrorist attacks in Australia have killed just three people (excluding the attackers). A terrorist attack, while 'probable' on the National Terrorism Threat Advisory System, remains unlikely to be the cause of death or serious injury for Australians.

There are several explanations for the discrepancy between the fear of terrorism, the perceived threat it poses to a nation, and the likelihood of it affecting an individual.

In an Australian context, despite the rarity of terrorist attacks in Australia, this has not been for the want of trying. Australian authorities have prevented multiple terrorist attacks from taking place. Australians have also been targeted or caught up in terrorist attacks overseas, most tragically in the Bali bombings of 2002 that killed 88 individuals and injured countless others.

As an immigrant nation, Australians are also connected to other parts of the world in a meaningful way. Mass casualty terrorist attacks in Europe or the Middle East resonate in Australia, particularly given the degree to which they dominate rolling news coverage. Finally, even where there is no personal connection to a terrorist attack, research has shown that prolonged exposure to the associated news coverage can trigger acute stress reactions.

In addition to these broadly rational reasons why the fear of terrorism in Australia is disproportionately high, there is one overarching factor that applies in Australia and elsewhere. While other risks and threats are much more likely to be the cause of death or serious injury, they are perceived as threats over which an individual has a large degree of control (even if reality does not match that perception). Or in the case of natural disasters, over which no one, including the government, has control.

Attempts to use statistics to demonstrate that workplace accidents or drowning in the bath are a more likely cause of death than terrorism, while laudable, are likely to be ineffective. They miss what is unique about the threat posed by terrorism: that it is a deliberate act of violence designed to kill or injure by an external 'other'.

For part two, click here.