Below, I tease out a few below-the-radar observations in the form of three questions. Each addresses the problem from a different angle.

1. Is the Trump Administration as serious about confronting North Korea as appears?

It's tempting to hang the tag of adventurism on an impulsive character like President Trump. Hands up, I raised that possibility before he entered office, though I believe the Administration was right to conduct a limited, punitive strike on Syria to protect the norm against chemical weapons use. In South Korea, Trump's talk of an 'armada' that failed to arrive off the Korean Peninsula as advertised confirmed the opposite suspicion, of bluster. Loose cannon or paper tiger?

Either way, the likelihood that North Korea will acquire the means to hit the US with a nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) on Trump's watch is a legitimate and serious concern, one that would lead any White House occupant to consider 'all options', at least until they discover how poor most of these are. Incoming US presidents tend to experience a similar learning curve on North Korea.

In 2002, when George W. Bush co-bracketed North Korea, Iraq and Iran as an 'axis of evil', many wondered if this prefigured military action to effect regime change in Pyongyang. It wasn't to be, in part because North Korea was a tough enough target then. But the real reason was because America's strategic attention was tuned to the Middle East, Iraq in particular. To be cynical, North Korea's addition to the axis ensured there wasn't an all-Muslim line-up of rogue actors. We know what happened next.

Donald Trump has neither the popular mandate for, nor the inclination to repeat, a foreign policy mis-adventure on the scale of Iraq. Yet when ISIS is eventually out of the way, there is a good chance that the inner core of Trump's national security line-up, led by McMaster and Mattis, intends to apply the squeeze on Iran.

If Tehran preoccupies the Trump Administration, what appetite will there be to escalate tensions in parallel with Pyongyang? Expectations that China will deliver for the US by persuading North Korea to reverse course on its nuclear track are very likely to be dashed, even assuming Beijing's coercive efforts are in earnest. But if the US prioritises Iran, the current 'phoney war' on the Korean Peninsula could continue for some time.

It's hard to know where Trump's instincts will draw him, but he has threatened to take care of the North Korean problem unilaterally if China's efforts fail. If the US manages to avoid sapping new commitments in the Middle East, we could see a renewed push for preventive strikes on North Korea next year. But Iran might get a veto on that.

2. What is the impact of a North Korean nuclear ICBM on extended deterrence and US alliances in Asia?

If US military options and China's leverage are so constrained that we have to learn to live with a nuclear North Korea, what will be the longer impact on US alliances? Hugh White touched perceptively on this in his recent post, in relation the impact North Korea's incipient ICBM capability will have on US pledges of extended deterrence to its Pacific allies. It's an important point worth thinking through.

Japan and South Korea rely on the US for extended deterrence, but how credible is this once Pyongyang acquires a second-strike and, perhaps, a thermo-nuclear capability against the US? Without the surety of the nuclear umbrella, will Japan and South Korea decide they have no choice but to arm themselves with an independent deterrent? That outcome is certainly not pre-ordained. After all, extended deterrence to US allies has accommodated China's ICBMs. But it becomes more likely once a North Korean nuclear ICBM comes into being. Even Australia now finds itself on the receiving end of nuclear threats from Pyongyang, during the visit of Vice President Mike Pence, though these are not to be taken too literally.

The logic of extended deterrence requires the US to risk, say, New York in order to save Tokyo, Sydney or Seoul. Now that Pyongyang is on the threshold of entering the elite intercontinental nuclear club, in the company of China and Russia, it should not surprise that the equation works in reverse. South Korea's nuclear umbrella holder, the US, may well be prepared to risk Seoul, now, to prevent a North Korean nuclear sword of Damocles from being suspended over the US homeland, later. Some see Trump's rush to confront Kim Jong Un as irresponsible, given the North's conventional artillery threat to Seoul. But such confrontation has an instinctive appeal, especially for a confirmed alliance sceptic like Donald Trump.

3. Trump has received attention as the new actor in the North Korean drama. What of the dynamic with Kim Jong Un?

Kim Jong Un was chosen over his elder brother Kim Jong Nam, who was probably killed on his sibling's orders, using VX nerve agent, in Malaysia's international airport in February. Jong Un was chosen for a reason. He visibly relishes the missile tests and parades that he frequently attends. He doesn't want to be remembered as North Korea's Deng Xiaoping, or some drab economic tinkerer. His signature Byongjin policy amounts to having his cake and eating it too. He wants to grow North Korea's economy while building up the acme of nuclear missile programs.

Kim Jong Un isn't interested in a back-burner, virtual deterrent to be traded away for heavy fuel oil, or security guarantees that in his mind aren't worth the paper they are written on, though that doesn't mean he won't demand them. He wants affirmation for North Korea as a nuclear weapons state, now written explicitly into the country's constitution, portraying this as the fulfillment his father's legacy. Kim Jong Un is fashioning a brand of nuclear fascism that fetishises the tools of mass destruction as ends in themselves, hard-wired into the country's domestic politics. He has proved himself both canny and ruthless, five years into the supreme leader role. He is in his element.

North Korea under Kim Jong Un isn't pursuing a minimalist nuclear hermit strategy for regime survival and the quiet life. Controlled, deliberate instability is part of the regime's DNA. Without external enemies, North Korea's domestic oppressions and privations will be laid bare for what they are: cruel and pointless strictures to perpetuate misrule by the Kim family. If North Korea's confrontation with the US flashes hot, it will be because Kim oversteps the line with Trump, or perhaps with China, now that Beijing's treaty ally is being openly labeled a latent enemy. A provocative test of South Korea's next president is also highly likely later this year.

For now, Kim has opted not to escalate beyond ICBM launcher parades and missile tests. But it is only a matter of time until the next nuclear trial. The most destabilising outcome from the current tensions would be if Kim concludes, as well he might, that Trump's bluff can be called, consequence-free.

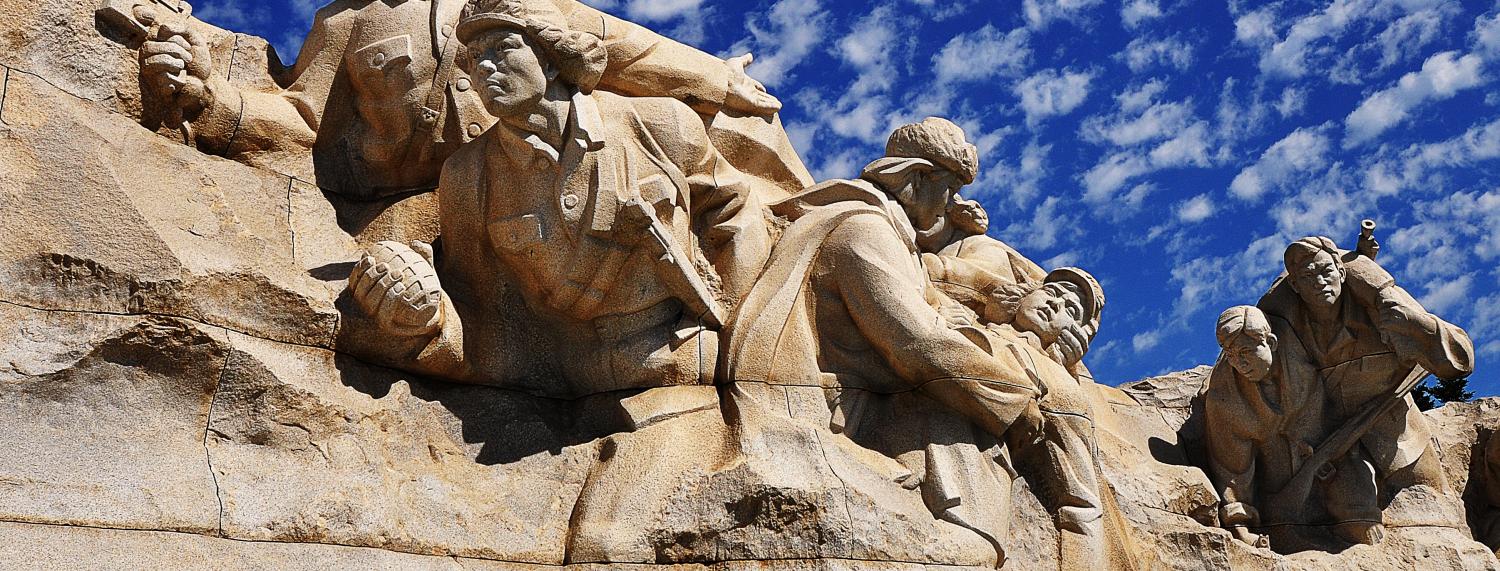

Photo by Flickr user Adaptor -Plug.