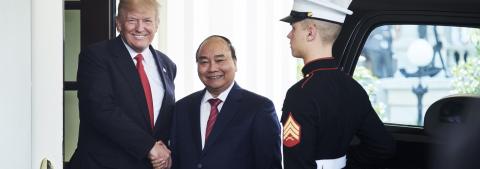

The most striking message of the Hamburg G20 leaders meeting is not that the US did not lead the discussion but that it clearly didn’t even wish to. President Trump is most comfortable as a belligerent outsider, not only in Washington but also among his fellow global leaders. His only friend on climate change was another outsider, Turkey’s President Recep Erdogan. Trump's most dramatic and evidently companionable meeting was with the most isolated figure at the meeting, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. Trump's major speech, the event Trump he is said to regard as his greatest success, was delivered alongside Polish President Andrzej Duda, who is not in the G20. Quite how Trump reconciles his grand call for the defence of Western civilisation with his reluctance to lead it is anyone’s guess.

Yet for all that, the weekend meeting did indeed continue the reluctant reintegration of the US president, begun in late May at the G7 in Taormina, Italy, back into the broad flow of the global economic discussion. If the G20 statement on trade was much the same as that agreed at Taormina, at least there was less quibbling about it.

That improved tone might reflect an increasing conviction among his fellow leaders that Trump’s trade bark is worse than his bite. It might also reflect Europe’s collective ability to demonstrably advance globalisation despite Trump’s rhetorical resistance. Well before the G20 leaders sat down Europe was able to announce a trade agreement with Japan, while for her part Germany’s Merkel had no hesitation in portraying a closer economic partnership with China.

But, more importantly, the declining clamour on global trade issues reflects a slow adjustment to reality.

Trump’s greatest rhetorical success continues to be his portrayal of the US as a global trade loser. The facts are otherwise, as other world leaders must know.

Unnoticed, unheralded, apparently with little impact on the US political debate, the American trade collapse complained of by Trump during the election campaign and since he came to office, has for some time been replaced with striking success.

As it happened, the success was most clearly evident under President Barack Obama. In each of the four years up to and including 2014, US exports were higher as a share of GDP than at any time in the last hundred years, and likely much longer. Even this year, US exports are running only a little below these records, compared to GDP.

To a lesser extent, the same is true of moderation in US imports, despite Trump’s complaints. Excluding the impact of the global financial crisis, by the time Trump won the presidency US imports compared to GDP were back down to where they had been a decade ago.

At 6% of GDP the US trade deficit was a big global issue in 2007. By 2016, the year Trump won the presidential election, it was half of that size compared to US GDP. (China’s trade surplus had fallen even more dramatically, from 9% to 2.2% compared to China’s GDP.)

The current account ‘imbalances’ said to risk the health of the global economy have likewise fallen, and also well before Trump became President. In 2007, during the administration of George W Bush, the US current account deficit was 5% of GDP. Last year it was half that, compared to GDP. China’s current account surplus, said to be the counterpart of the US deficit, has shrunk much more dramatically. It was one tenth of GDP in 2007, and under 2% last year.

So the US is actually doing very well in global trade – in exports, better than ever.

To a large extent, Trump’s election campaign ran on the memory of a deterioration in the US trade and current account balance that was already repairing itself. This was also true of output growth and employment. The US economy is now enjoying one of the longest upswings since the second world war. At 4.4% in June, the unemployment rate is just a tad above the recent and exceptional low of 3.9% reached just before the 2001 ‘tech wreck’ and otherwise the lowest in nearly half a century. The European leaders to whom Trump complains of trade troubles would regard these outcomes as brilliant, if attained in their own economies.

They don’t say so, but European leaders probably also recognise that US presidents are usually difficult on trade issues, and for all his efforts Trump has yet to prove himself more unsatisfactory than his predecessors.

The recurrent motif of discussion of the trade policies of the Trump Administration is that they are new, hard-edged and disruptive to the global economic order. So far at least, that is not actually true. On the contrary, Trump is very much in the tradition of his predecessors, both Republican and Democrat, and distinguished from them only in the candour with which he advances US interests.

Trump has not only failed to match up to his own campaign rhetoric on trade, but also failed to match up to the trade belligerence of some of his predecessors.

His commitment to impose a 45% tariff on China and Mexico are long forgotten, along with the promises to declare China currency manipulator on ‘day one’, and to dump the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The Trump administration's more recent trade belligerence is also less distinctive than it appears.

According to Chad P Bown writing recently for the Petersen Institute of International Economics, if the administration does indeed follow through on threats to impose more protectionist measures, the share of US imports covered by anti-dumping protection and countervailing duties and so forth will increase.

But Bown’s painstaking quantification of protectionist measures put in place by recent past administrations also demonstrates that Trump’s initiatives are nothing new. Starting in the last two years of the George W Bush administration and continuing under President Obama, the share of China’s exports to the US covered by barriers under US trade laws more than doubled, from 4.5% to 9.2%. On Boown’s reckoning, if all of Trump’s threats were carried out, the share of China exports covered by these protectionist measures would rise to 10.9% - a much smaller increase than that under Bush and Obama.

There would be a much bigger impact on imports from the rest of the world – including, prominently, Germany, Canada and South Korea. The share of non China imports covered by these measures (countervailing duties and anti dumping measures) could rise to 6.6%, from 2.2% now.

It is notable that the principal exporters of steel to the US are now Canada, Germany and South Korea, all close US security allies. They are the countries likely to be hurt most by the new import restrictions the Trump administration is threatening to invoke on ‘national security’ grounds. China is by contrast a minor source of US steel imports, not because it lacks capacity but because previous US administrations imposed tough restrictions on it. Those who are - according to the administration - the chief offenders now, are also some of America’s best friends. Turkey, Russia and Poland are fine friends, but they lack the long intimacy, strategic consequence, and capacity for retribution of Canada, Germany and South Korea. The likelihood of actually imposing such imposing new protections in a big way is surely very small.