Are Australia and China frenemies?

Are Australia and China frenemies?

Michael Fullilove

The Guardian

Please click here for full online text.

It is remarkable that so many Australians believe we may soon be threatened militarily by a country that many of us today see as our best friend in Asia

Executive Summary

The 2014 Lowy Institute Poll, released this week, demonstrates that when it comes to China, Australians feel very conflicted.

On the one hand, Australians’ feelings towards China are as warm as they have ever been in 10 years of Lowy Institute polling. Remarkably, Australians believe that China has as much of a claim to the title of "Australia’s best friend in Asia" as Japan has – and a greater claim than Singapore, Indonesia, India or South Korea.

On the other hand, nearly half (48%) of Australians believe it is likely that China will become a military threat to Australia in the next 20 years. More than half (56%) believe the government allows too much foreign investment from China.

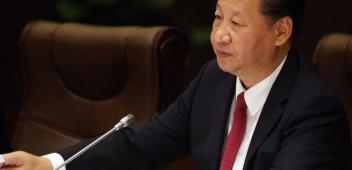

And China’s powerful new leader, president Xi Jinping, hardly registers in the Australian public consciousness. When asked to rate a series of world leaders, only 2% of Australians said they admired Xi a lot, and 15% admired him a little. A full 64% did not know of Xi or had no view of him.

It is remarkable that so many Australians believe we may soon be threatened militarily by a country that many of us today see as our best friend in Asia. But it is also understandable that Australia and China should not have a complete meeting of the minds. On the one hand, there is much for Australians to admire about China’s development. In the past three decades, China has remade its economy, driven extraordinary productivity increases, and in so doing raised hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This last achievement should not be ignored by China’s critics.

China’s economic growth and its appetite for natural resources has, of course, put a good deal of money into Australians’ pockets in recent years. Increasingly, flows of trade and investment flows are being matched by flows of people, as Australian and Chinese tourists discover each others’ countries.

On the other hand, our two countries remain starkly different. There are limits to the level of intimacy that can be achieved between a democracy and a non-democracy. This week’s anniversary of Tiananmen Square is a reminder that internal conditions in China have the potential to derail the bilateral relationship.

Furthermore, China’s external behaviour has taken a more assertive turn of late. Last year, China unilaterally announced an air defence identification zone over the East China Sea, provoking strong responses from Australia and other countries. In early February, Chinese warships conducted their first military exercises in the waters immediately to Australia’s north.

Given the uncertainty about China’s future behaviour, it makes good sense for us to invest in our alliance with the United States and encourage its "rebalance" towards Asia. But this does not mean we should run down our relationship with China; on the contrary, we should thicken it.

What can we do to take the Australia-China relationship to the next level?

The strategic partnership delivered by former prime minister Julia Gillard in 2013 was a good start. Australian and Chinese political leaders do not know each other well enough. Now Australian and Chinese leaders are due to hold annual meetings each year and Cabinet-level strategic dialogues on foreign policy and economics are also meant to take place. The Lowy Institute has long argued for this kind of arrangements to build trust between the political elites of the two countries.

In April, prime minister Tony Abbott pulled off a successful visit to Beijing. Taking a leaf from John Howard’s book, he stayed away from human rights and focused instead on areas of common interest, in particular economic ties. He was assisted by the professionalism showed by Australian agencies in the search for MH370 – a topic in which the Chinese leadership is intensely interested.

This November, president Xi is due to visit to Australia in November for the G20 Leaders Summit. Hopefully he will stay for longer than the summit, and see more of Australia than Brisbane.

When it comes to Asian security, Canberra needs to walk a fine line. We should not get caught up in bilateral disputes in which we cannot make a material difference – but we should not back off from defending our own interests and values. I have never heard a sinologist say that the one thing the Chinese respect is weakness.

The worst thing we could do is lead the Chinese to believe we will pre-emptively downgrade our alliance relationship with Washington in order to curry favour with Beijing. That is never going to happen and any hints to the contrary will only lead to disappointment down the track.

China appreciates clarity and consistency in its relations with other countries, and Australia owes it no less than that.