Eyes on the Prize: Australia, China, and the Antarctic Treaty System

Despite China’s increasing assertiveness in Antarctica, the Antarctic Treaty System is not failing and Australia should refrain from geostrategic panic

- Australia’s interests in Antarctica are better served by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) than anything we could negotiate today. We should redouble our commitment to its ideals of science-driven, rules-based management — and counter the narrative of ATS ‘failure’.

- China is pushing the boundaries of ATS practice by exploiting fisheries and tourism, and probably seeking access to Western technologies in Antarctica. And in the future, Beijing could lead a coalition of states seeking mineral riches that only China is likely to be capable of retrieving.

- Australia should watch China’s activities closely, but react cautiously. We should be wary of false analogies with the Arctic and not overreact to marginal military developments. We should shield the ATS from Australia–China tension and US–China competition.

Executive Summary

What is the problem?

The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) provides Australia with a peaceful, non-militarised south; a freeze on challenges to our territorial claim; a ban on mining and an ecosystem-based management of fisheries. But China wants to benefit economically, and potentially militarily, from Antarctica. It is increasingly assertive in the ATS, primarily over fisheries access, and active on the ice.

What should be done?

Australia should front load its support for the ATS, increasing both the substance and profile of our Antarctic activities. We should emphasise ATS ideals rather than our claim to Australian Antarctic Territory (AAT). We should work hard internationally to dispel the myth that Antarctica’s resource wealth will be unlocked in 2048 on review of the Madrid Protocol. Inside the ATS, we should play to our strengths in multilateral diplomacy. Canberra should monitor Chinese activities in Antarctica and the ATS and step up its maritime awareness of the Southern Ocean, but refrain from geostrategic panic.

Introduction

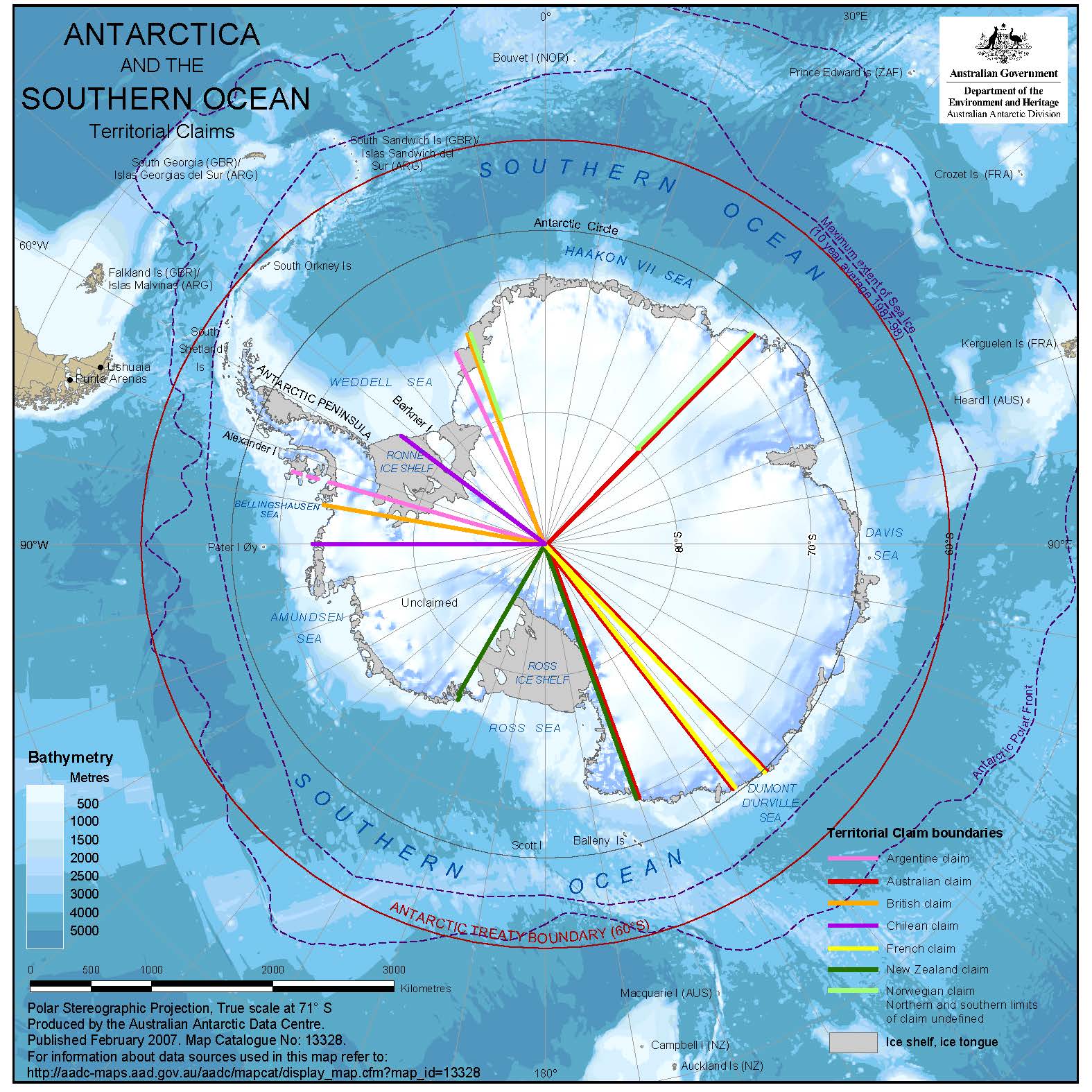

What the Antarctic Treaty System gives Australia

The Antarctic Treaty requires that Antarctica be used only for peaceful, scientific purposes (Box 1). The Treaty also ‘freezes’ challenges to our claim of the Australian Antarctic Territory (AAT) — the largest of the seven claims, at around 42 per cent of the continent. Without the Treaty and its supporting agreements, Australia could not afford to defend the AAT, ensure a non-militarised southern border, or prohibit mining in the area. We cannot assume that our historical and current activities would be sufficient to legally assert ownership of the Antarctic region directly to our south if the Treaty failed.

Argentina, United Kingdom, Chile, France, New Zealand, and Norway. Image: Courtesy Australian Antarctic Division.

The Treaty is a Cold War relic, which means that it is better for us than anything we could negotiate today. Despite its idealistic foundation story — building on the scientific cooperation of the 1957–58 International Geophysical Year — the real impetus was the determination of the United States, the USSR, and the United Kingdom to deny their rivals control of the continent without opening a costly new front in the Cold War.[1] Peace, science, and a pristine environment open to all, were convenient and popular alternative rationales.

The Treaty does not give us everything we might like. Our ‘sovereignty’ over the AAT is not fully protected. We cannot stop a research station being built in the AAT, and our laws apply only to Australians.

The Treaty does, however, give us a voice in the consensus forums of the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), including a host of scientific and practical committees and the annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) where we have a vote along with the other 29 signatories that conduct substantial scientific research on the continent. Diplomatic and scientific entrepreneurialism and detailed negotiations do most to protect our interests. Consensus decisions in ATS forums are mostly respected once reached, and there is a strong tradition of scientific cooperation, international rescue efforts, and environmental protection.

Box 1: The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) at a glance

The Antarctic Treaty entered into force in 1961, signed by 12 states. It now has 54 parties. Currently, 29 states are Consultative members with voting rights in Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs). States are granted Consultative status after demonstrating a significant commitment to scientific research in Antarctica.[2]

Signatories agree to Antarctica being used for peaceful, scientific purposes only. Military equipment and personnel can be used only in support of science and logistics. Station facilities and vessels can be inspected by other states. Scientific results and plans must be shared.

Challenges to the seven territorial claims on mainland Antarctica are ‘frozen’ in that nothing supports or denies them while the Treaty is in force, and no new claims can be made. Outside the Treaty, only some states with their own claims recognise others’. The United States and Russia have reserved the right to make a claim.

The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) refers to the Treaty and related agreements. An important agreement is the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR), which entered into force in 1982.[3] It has 26 voting members, and 10 more states have signed but are not engaged in fishing or research and therefore cannot vote. All decisions, including on Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), are made by consensus.

Another major agreement is the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, known as the Madrid Protocol, which among other protections prohibits mining.[4] It entered into force in 1998. It allows for review in 2048, but sets a very high bar for change: agreement by three quarters of states who were Consultative members to the Antarctic Treaty in 1991, and then ratification by three quarters of Antarctic Consultative Parties, including all states that agreed to the Protocol in 1991. No mining can commence until agreement on the conditions for mining are negotiated and ratified. That agreement also requires that the interests of claimant states (such as Australia) must be safeguarded.

The Madrid Protocol to the Treaty prohibits mining, which Australia supports for environmental reasons and to avoid the continent becoming an area of contention. Even if Australian attitudes on this change, mining on the continent is unlikely to be profitable within the foreseeable future, although seabed mining below 60° south (the Antarctic Treaty area) is conceivable. Fear of missing out on imagined future riches still drives Antarctic funding in many states, but the Protocol sets a high threshold for reversing the ban.

Consensus decision-making, however, means it is easy to stymie initiatives, particularly with the growing number of member states in the ATS. Currently, 29 states have voting rights at the annual Treaty meeting; in 1989, when Australia and France proposed prohibiting mining, it was 22.

There is limited scope to ensure compliance with ATS rules and provisions. The Treaty allows inspections of stations to ensure they follow ATS rules and respect the prohibition on military use. However, Antarctic logistical constraints usually mean that stations have prior notice of visits, few observers are involved, and inspections are brief. The body dealing with fisheries — the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) — requires that observers and reporting systems are placed on fishing vessels, and vessels or states can be deemed non-compliant, but listing a state as non-compliant requires consensus agreement. China and Russia have recently refused to let their vessels be sanctioned.

What China wants from Antarctica

To shore up its domestic rule, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) needs to keep China’s economy strong, secure technological leadership, and demonstrate China’s power in global affairs. In Antarctica, that translates into growing exploitation of fisheries, Chinese ownership of tourism opportunities, access to Western technology through joint projects, and international acquiescence to China’s preferences in the ATS. Before 2016, China’s Antarctic stations and science seemed designed to position it for a territorial claim in the AAT if the Antarctic Treaty were overturned at some point in the future.[5]

signed on 1 December 1959 in Washington, DC. Image: Josh Landis/National Science Foundation.

But China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020) set out an ambition to “build China into a strong maritime country”, with a clear emphasis on fisheries and other economic opportunities.[6] China has increased subsidies for fuel, and grown its ship-building program for China’s distant-water fishing fleet.[7] Access to marine resources and tourism opportunities across the continent are now the more pressing drivers of China’s Antarctic activities.

It is likely that Beijing also wants to keep open the possibilities of seabed mining, a territorial claim, and the use of civil equipment on the continent for military advantage. So, although China will support Antarctic agreements over at least the next few decades, it will keep pushing to change the practices and purposes of the ATS from within to meet its current and future interests.

What Australia should do: Policy recommendations

1. Promote the ATS as an example of a successful rules-based system

Australia is striving to build a more rules-based order globally, and preserving the ATS should be an important priority.[8]

Antarctica is physically and historically unique, which means the ATS does not offer a simple template for other territorial regimes (Box 2). But Antarctica does demonstrate that even in the current era of strained relations, Australia, the United States, China, and others can cooperate in a rules-based system. As the world tries to tackle climate change, the ATS also shows what can be done when science is the basis for action — even when science is inevitably directed in part towards state ends.

Box 2: Spot the difference: the Arctic and Antarctica

The Arctic and Antarctica are significantly different strategically and geographically. The Arctic is an ocean, mostly shallow and relatively lightly covered by ice, surrounded by land that extends across the Arctic Circle. Much of the Arctic is covered by Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) or seabed formations extending directly from states’ home territories. Antarctica, by contrast, is land rimmed and almost entirely covered by a thick layer of ice, surrounded by deeper seas with only a few small, scattered islands.

The Arctic’s sea-ice is reducing dramatically with climate change. As a result, Arctic resources — such as fish, minerals, and hydrocarbons — and shipping routes are likely to be much more accessible over coming years. Antarctica’s thick ice, thousands of metres deep in places, is also melting, changing local ecosystems[9] and promising metres of global sea level rise over several centuries.[10] But climate change is unlikely to make Antarctic resources other than fish or krill more accessible in the same timeframe as in the Arctic. One of the few similarities is that climate change is driving fish species towards both poles.

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum of the eight states with territory or maritime jurisdiction in the Arctic.[11] Observers are admitted only by agreement of the eight members and have no voting rights, so China and others interested in Arctic resources are disadvantaged. Beijing is trying to buy its way in with science, funds, and infrastructure.[12] By contrast, any state can sign the Antarctic Treaty, any Party can conduct science there, and any state can vote if it conducts credible scientific programs in Antarctica. China is there by right.

The Arctic separates two nuclear-armed adversaries — the United States and Russia — so it already has military forces and infrastructure, and easier access will worsen geostrategic tensions. The Arctic Council does not deal with security issues or prohibit military activities in Arctic high seas. By contrast, the Antarctic Treaty prohibits military use of Antarctica and there are no military facilities. Southern Ocean waters have not been widely used for military purposes, and all vessels are free to transit high seas within the Treaty area.

Russia already extracts hydrocarbons from the Arctic, but mining in the Antarctic Treaty Area (up to 60° south) is prohibited under the Madrid Protocol. In any case, hydrocarbon extraction in Antarctica is unlikely ever to be economically viable. Even if clean technologies increase demand for minerals found as nodules on the sea floor, such as cobalt, there are easier places than Antarctic waters to be exploited first.

Australia should work to ensure that US Antarctic policy under President Joe Biden is integrated into the new US administration’s commitment to a more rules-based global order, that it is not dominated by competition with China, and that it continues to accord with the ideals and norms of the ATS.[13] China’s compliance with the ATS needs to be monitored, but Antarctica should not become another arena for great power competition.

Australia should actively promote the achievements and ideals of the ATS: peace, non-militarisation, scientific research, and ecosystem-based sustainable fishing. The Madrid agreement was founded on the assessment that mining on the continent was not economically feasible, combined with the public appeal of wilderness. These fundamentals are unchanged.

We should work hard internationally to dispel the myth that Antarctica is a pot of gold that will be opened in 2048 when the Madrid Protocol could technically be reviewed. The idea that the Protocol (or worse, the Antarctic Treaty) ‘expires in 2048’ is fed by commentary portraying the ATS as weak[14] and implying that its collapse is inevitable.[15] We should commission polling in Australia and elsewhere to determine the depth of public support for Antarctica as a place dedicated to science.

Now is the time for us to reiterate the benefits of a functioning ATS for all member states: scientific status, practical understanding of changing global weather and currents, and an increasingly valuable sustainable fishery. As climate change and overfishing place increased pressure on all fish stocks, precautionary management of Antarctica’s fisheries needs to be seen as preserving a resource for all CAMLR Convention signatories; not as a Western environmentalist luxury. All Treaty members, not just Australia, stand to lose if the ATS falls apart.

We should be guided by a policy of engaging and balancing China, and keep the ATS free, as far as possible, of Australia–China tensions. There are principles we cannot resile from, such as precautionary fishing regimes and the monitoring of states’ compliance with ATS obligations. But many ATS meetings focus on practical, day-to-day issues, where Australian and Chinese collegiality in science and logistics continues — as evident in the recent rescue of an Australian expeditioner.[16] We should avoid being at the forefront of every dispute over Chinese actions in Antarctica.

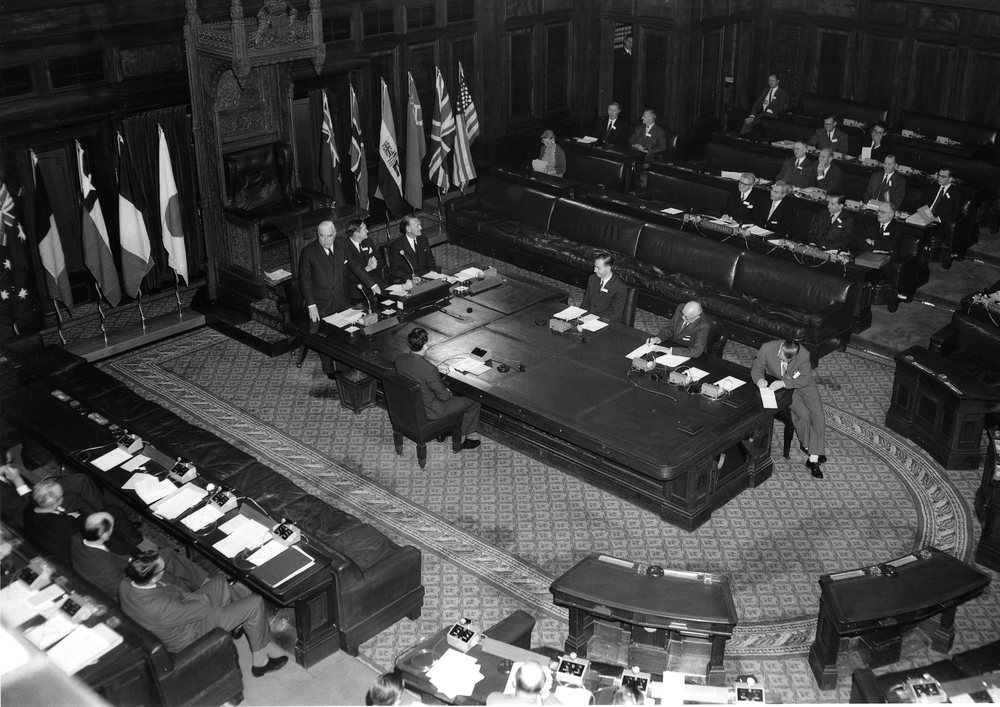

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies at the podium. Image: Australian Government, “The First ATCM,” ATS Image Bank,

accessed February 15, 2021, https://atsimagebank.omeka.net/items/show/72.

In promoting the ATS internationally, Australia should not highlight its claim over the AAT. This is not to suggest Australia back away from its claim. But drawing international attention to the AAT helps China and Russia insinuate that claimants propose MPAs only to extend their sovereignty.[17] Our support for MPA proposals beyond the AAT helps.

2. Assess China’s behaviour realistically

Canberra should avoid overreacting to alarming public analyses of Chinese activities in Antarctica. Tensions over fisheries are real, but need not be viewed as geostrategic conflict. Talking or acting as though we are already in crisis distracts from the long-haul effort of protecting our interests in the ATS.

There are public fears that China is using some technologies and equipment in Antarctica for military purposes (Box 3).[18] Unfortunately, the Treaty’s prohibition on the use of military equipment other than to support science and logistics is open to broad interpretation.[19] Judging breaches requires assessing whether the equipment supports scientific research, comparisons with other states’ actions, and a thorough assessment of any military advantage in a global context.[20]

The United States withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) in 2019 only after it became clear that Russia was not only flouting its rules, but also putting the United States at a substantial disadvantage. There is no sense in risking the ATS without a similar weighing of interests. If we are to rally other states against a violation of the Treaty, our case needs to be clear, provable, and of strategic importance. The non-militarisation provision implies any equipment breaching the provision would have to be withdrawn under suasion, rather than by force.

Antarctica’s non-militarisation could be advanced in several ways: commissioning technical specialists to conduct classified and open-source reviews of dual-use (civil–military) technologies and equipment in the region; continuing the recently revived program of Australian and multilateral inspections of stations by qualified personnel; and holding at least annual policy and intelligence discussions with Five Eyes partners. (As an Arctic state, Canada would have deep interest in Chinese polar policy.)

Box 3: Has China really breached the non-militarisation provision?

Ground reference stations for China’s GPS-equivalent system, Beidou, were installed in China’s Zhongshan and Great Wall stations in 2010, and Kunlun in 2013.[21] Like the US GPS and Russian GLONASS installations, they are allowed by the Treaty to assist science and logistics.[22] Antarctic ground stations may be slightly more important for the precision of Beidou than for GPS since most of Beidou’s stations are in the northern hemisphere. But from a military perspective, the increase in precision of delivery of missiles or other weaponry is marginal, especially as South American and African states are hosting more Beidou reference stations.[23]

There are also concerns that China’s high-frequency radar equipment can jam US satellites.[24] By sending a signal in the same frequency as a satellite’s up or downlink, this is technically possible. However, jamming an uplink takes a great deal of power and jamming a downlink requires proximity to the receiver, and US stations are not co-located with Chinese ones. Either way, jamming is usually temporary.[25] On the whole, Chinese radars in Antarctica would have little military value, but they provide legitimate support for science, as do similar systems fielded by the United States and others.

China’s telescope on Dome Argus (‘Dome A’),[26] technically similar to the US telescope at the South Pole, has been suspected of having a military use. Telescopes can contribute to space awareness by slowly building up databases of satellites passing overhead, which helps all satellites — civil and military — avoid space junk. But a Chinese telescope in Antarctica would contribute only marginally to data easily available from telescopes and other equipment in other parts of the world.[27]

China is also suspected of prospecting with a view to mining the Antarctic sea floor in the future, consistent with its stated interest in the global commons and the marine economy. Yet, the line is blurry between geological exploration, which is allowed under the Treaty, and prospecting with an eye to future mining,[28] which is not.[29] We should investigate any exploitation of this ambiguity, but not overreact.

Even after 2048, when review of the Madrid Protocol’s ban on mining becomes easier, agreement will still be slow and difficult. Technological advancement in seabed mining is slow,[30] the International Seabed Authority’s Mining Code is delayed and its mechanism for sharing profits among states unclear, future demand for minerals is unknown, and other seas would be preferable over the deep and stormy Southern Ocean.

Calls for military preparations against such a day may exacerbate the problem.[31] They fuel emerging economies’ suspicions that Western environmental concerns are cover for denying other states a share of the economic spoils. We should be arguing internationally now for the Southern Ocean to remain a reserve, noting that all states will benefit from mining other oceans under International Seabed Authority (ISA) rules. Commissioning public research into the potential impacts of undersea/seabed mining below 60° south on increasingly valuable krill and fish stocks could also help inform states’ attitudes.

3. Play to our multilateral and Antarctic strengths

China’s approach to the ATS resembles its increasingly assertive conduct in other international organisations. Beijing has tried to change the language of ATS meetings to redirect their purpose from ‘protection’ as well as ‘utilisation’ of Antarctica to favour ‘utilisation’. Chinese officials tried to give the two terms equal weight at the 2017 Treaty meeting in Beijing.[32] At the 2019 CCAMLR meeting, China refused to accept it was non-compliant even on a minor issue,[33] exhorting members to “come back to the right path towards mutual respect and win-win cooperation” — terminology China uses in the United Nations (UN) and elsewhere when it rejects multilateral constraints.[34] China also criticised Australia for non-compliance, a form of offence-as-defence displayed in other forums.

In UN bodies and other multilateral forums,[35] China has sought to use its larger diplomatic and scientific resources to rewrite policies. It is now doing the same in CCAMLR, demanding — and then undertaking — more scientific research before even considering new MPAs.[36] Beijing also invokes precedents it has established in other organisations, such as the UN Development Programme. Moves like this carry an implied threat, as ATS members generally want to keep Antarctic matters out of global forums.[37]

Australia should point out China’s tactics to other states and, as in other rules-based systems, work with more and wider groupings. The claimant states are a natural grouping, but we could also help aspiring Consultative members, such as Turkey, with their Antarctic science and diplomacy, partly to underline that the ATS is not a rich-world club.

Australia should forestall the emergence of a ‘fishing bloc’. China’s pursuit of utilisation over preservation of Antarctica could rally support for such a bloc.[38] Russia and other fishing countries already adopt some similar positions to China in the CCAMLR.[39] To counter this trend, we should build influence with these countries through cooperation in logistics support, environmental clean-ups and tourism policy. We need to stand with states that challenge fisheries abuse, as New Zealand recently did when it detected a Russian craft spoofing its vessel-monitoring device while fishing in a closed area many kilometres away.[40]

More than 56 000 tourists visited Antarctica in the 2018-2019 season. Image: Ronald Woan/Flickr.

Other potential groupings are the five states closest to Antarctica — Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina, and Chile — that host ‘jumping-off’ ports. Of these, Chile,[41] Argentina,[42] and South Africa[43] contend with Chinese fishing fleets in or near their waters beyond the geographic remit of the ATS. Consistent with our increasingly diverse work in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (with the United States, India, and Japan) we should work more closely with those countries. The United States is already a close partner for Australia in the ATS, despite its non-recognition of our claim.[44]

We should make the most of Chinese efforts to boost their environmental credentials. Beijing signed the CAMLR Convention when Chinese vessels were on the illegal vessels list and agreed (after tough negotiations)[45] to the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) in 2016 to boost its standing with the environmentalist US Secretary of State John Kerry. Beijing recently joined a voluntary, temporary ban on krill fishing close to penguin habitats on the Antarctic Peninsula.[46]

However, if we are to work effectively with others to engage China’s desire to appear environmentally responsible, our wider environmental policies need to be consistent. For some countries, our influence in Antarctic matters will depend on our attitude to resource extraction in the Great Australian Bight, our stance on global sustainability such as World Trade Organization measures to reduce fuel subsidies to distant-water fishing fleets, and especially our climate change policies.

4. Keep up our Antarctic science and investment

The impact of COVID-19 on Antarctica could be more enduring than a temporary reduction of our science in the region. There is a risk that economically-hit like-minded states may reduce Antarctic spending for years, while China returns to its usual pace. Putting more resources into science, logistics, and diplomacy is the most effective way to pursue our Antarctic interests.

Reducing our research output relative to others’ would lower our status, since science and Antarctic experience underpin many ATS debates. It would also weaken our presence in the AAT and undermine our claim under international law should the Treaty one day fail. The 20 Year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan, produced in 2014 by former Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) director AJ Press, found that “Australia’s standing in Antarctic affairs is eroding because of historical under-investment at a time when new players are emerging” — a reference predominantly to China.[47]

Subsequently, over a 12-month period in 2018, Australia announced a replacement polar research vessel, a restored land transport capability, and scoping work for a new year-round airfield. These projects increase our access to the AAT, as well as support our scientific effort.

The airfield is the most expensive item and the government should provide sufficient funding in forward budgets. Environmental concerns about the airfield — some genuine and some stalking horses for impeding greater Australian access — are likely to cause substantial delays.[48] Committing funds will signal determination and credibility.

We should develop policies for emerging issues, such as tourism protocols, air safety, and aerial surveillance of fisheries compliance. The permanent airstrip China is planning in the Larsemann Hills could provide tourist access to the AAT and increase the need for air safety measures.[49] On the surveillance issue, China’s characteristically legalistic response when Russia objected to New Zealand’s air observation of one of its vessels demonstrates the need for policy development.[50]

Our science should meet ATS ideals — particularly openness and relevance to all. The new Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan heads in the right direction, with an emphasis on global concerns of climate change, Antarctica’s impact on global weather, and the sustainability of marine living resources.[51]

weather monitoring stations, and seismometers on icebergs to track their movements. Image: Josh Landis/National Science Foundation.

Our participation in the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Krill Action Group (SKAG) with scientists from the United States, Europe, China, and Argentina helps us ensure an ecosystems-based approach to krill fishing limits. As the United Kingdom has done, we could work with China on sampling krill distribution, making it harder for data to be cherry-picked.

Australia could also reduce friction over Chinese activities at Dome A[52] in the AAT by offering to participate in research with China there, fully funding our involvement as equal partners. In the past two years, Treaty members have rejected Chinese proposals that sought special treatment for the isolated station. A joint project between China and Australia would justify a joint Code of Conduct for the area.[53]

5. Don’t reach for military tools

ATS tensions cannot be productively addressed with military means. Any Australian use of military capabilities in Antarctica, other than for logistic support for science, would unnecessarily risk the ATS as a whole, from which Australia gains so much.

We should not invest in military vessels designed for polar operations to meet unlikely contingencies. If trade routes to our north were closed by a major war, Australian trade could transit ice-free Southern Ocean waters, with a protective Royal Australian Navy (RAN) submarine or surface presence. Those vessels would not need to be ice-breakers or even ice-capable, just able to operate in the Southern Ocean.

Specialist polar vessels cannot be justified by an extreme scenario of China leaving the ATS in the 2050s after failed Madrid Protocol negotiations, and mining the AAT sea-bed: it would make more sense for China to make commercial arrangements with more conveniently-placed South American claimants. In any case, such vessels would be unreliable in our northern waters, where we are more likely to need a presence.[54]

Our Antarctic interests should be supported with other means: stepped-up intelligence collection and analysis outside Antarctica, and more international cooperation against illegal fishing. We should coordinate our fisheries patrols with New Zealand’s proposed ice-hardened naval vessels[55] and return Maritime Border Command’s Ocean Shield to patrolling our sub-Antarctic islands (which it has not done since 2015, leaving Australian Border Force officers to ride on French vessels).

We should make more use of aerial, remote, unmanned, and satellite surveillance capabilities. These are already needed to meet our Southern Ocean Search and Rescue (SAR) responsibilities. Remote monitoring would provide cover for more of the year than surface vessels do. More research into Southern Ocean weather, and more mapping by Australia’s new research vessel Nuyina, would also improve SAR capabilities and expand our reach in the AAT.

Xi Jinping has directed that civil science should support military capabilities. So for Australian scientists there is an ongoing risk that their Chinese counterparts may take advantage of joint access to Australian equipment, particularly that used in marine or large-area surveillance and monitoring. Marine surveillance capabilities — sonar, buoys, and satellites — are all highly relevant to military operations in the South China Sea.[56]

These risks could be mitigated by:

- commissioning the government’s Defence Science and Technology Group to review equipment used in Antarctica or shared with Chinese scientists to identify any novel technology to which access should be controlled;

- assessing, with Five Eyes partners, any links between civilian Chinese (and potentially Russian) Antarctic scientific organisations and military ones; and

- ensuring AAD staff are briefed on Beijing’s willingness to use covert as well as overt means to gain influence or access to technology.[57]

Conclusion

Antarctica is not, and cannot be, fully quarantined from China’s more assertive foreign policy, which in Antarctica is now focused on fisheries access. In the future, Beijing could also lead a coalition of states seeking mineral riches that only China is likely to be capable of retrieving. But the effort China is putting into pushing the boundaries of the ATS from within demonstrates a strong preference to stay in the Treaty. Australia’s most efficient means of slowing or stopping these efforts remains well-funded collective diplomacy and science. We can still veto initiatives, even if our own are stymied.

Although ATS commitments are not always complied with fully, powerful states seeking an outsized share of resources beyond their national jurisdiction can be swayed by smart diplomacy and international public opinion. Antarctica is still remarkable enough, in its wilderness, scientific cooperation, and governance, that with concerted effort it has a chance of remaining separate from the worst of international geopolitics and exploitation.

About the author

Claire Young is a former senior analyst with the Australian Government, who covered Antarctica as well as emerging issues such as climate change, social cohesion, and water stress. Ms Young has worked on Australian security issues for over 40 years, including strategic policy analysis in the Department of Defence and writing for the Pacific Defence Reporter, a magazine established by her family.

Notes

Banner image: Australia's Davis research station, Antarctica. Courtesy Australian Defence Force.

[1] Klaus Dodds, “The Great Game in Antarctica: Britain and the 1959 Antarctic Treaty”, Contemporary British History, Vol 22 Issue 1, 2008, 43–66, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03004430601065781.

[2] The Antarctic Treaty 1959, https://documents.ats.aq/keydocs/vol_1/vol1_2_AT_Antarctic_Treaty_e.pdf.

[3] Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention-text.

[4] Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, https://documents.ats.aq/keydocs/vol_1/vol1_4_AT_Protocol_on_EP_e.pdf.

[5] Clive Hamilton, “Polar Progress: We Ignore Beijing’s Antarctic Ambitions at our Peril”, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 February 2018, https://www.smh.com.au/world/polar-progress-we-ignore-beijings-antarctic-ambitions-at-our-peril-20180220-h0wdc9.html.

[6] The 13th Five-Year Plan for the Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China (2016–2020), 2016, Chapter 41, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policyrelease_8233/201612/P020191101482242850325.pdf; see also Nengye Liu, “The Rise of China and Conservation of Marine Living Resources in the Polar Regions”, Marine Policy, Vol 121, November 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104181.

[7] Zhang Zizhu, “Decision Time for China on Fishing Subsidies” The Maritime Executive, 28 August 2020, https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/decision-time-for-china-on-fishing-subsidies.

[8] Ben Scott, “But What Does ‘Rules-Based-Order’ Mean”, The Interpreter, 2 November 2020, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/what-does-rules-based-order-mean.

[9] “Antarctic Krill Take Refuge from Climate Change”, British Antarctic Survey, 22 September 2020, https://www.bas.ac.uk/media-post/antarctic-krill-take-refuge-from-climate-change/.

[10] Robinson Meyer, “A Terrifying Sea-Level Prediction Now Looks Far Less Likely”, The Atlantic, 5 January 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/01/sea-level-rise-may-not-become-catastrophic-until-after-2100/579478/.

[11] Arctic Council https://arctic-council.org/en/.

[12] Elizabeth Buchanan, “Russia and China in the Arctic: Assumptions and Realities”, The Strategist, 25 September 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/russia-and-china-in-the-arctic-assumptions-and-realities/.

[13] In contrast, see Trump’s Presidential Memorandum, Memorandum on Safeguarding US National Interests in the Arctic and Antarctic Regions, issued 9 June 2020, for an example of geopolitical contest in the Arctic almost overwhelming any concern for the non-militarisation of Antarctica, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/DCPD-202000434/html/DCPD-202000434.htm.

[14] Sergey Sukhankin, “Is Russia Preparing to Challenge the Status Quo in Antarctica? (Part Two)”, Eurasia Daily Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, 24 June 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/is-russia-preparing-to-challenge-the-status-quo-in-antarctica-part-two/.

[15] Elizabeth Buchanan, “Canberra Shouldn’t Use COVID-19 as an Excuse to Ignore Competition for Antarctica”, The Australian, 7 October 2020, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/canberra-shouldnt-use-covid19-as-an-excuse-to-ignore-competition-for-antarctica/news-story/f09969fa2499c4ae9b36c0f8bda3cbad; see also Matthew Bieniek, Dan Ellis, David Groce, Kerryn McCallum, and Alice Paton, “Post-COVID World”, The Perry Group Paper, The Forge (Australian Defence College), undated, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/Post-COVID%20World_0.pdf.

[16] “China Helps Evacuate Sick Australian from Antarctica in Five-Day Mission”, The Guardian, 25 December 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/25/china-helps-evacuate-sick-australian-from-antarctica-in-five-day-mission#:~:text=Australia%20and%20China%20have%20collaborated,kilometres%20of%20the%20icy%20continent.

[17] Klaus Dodds and Cassandra Brooks, “Antarctic Geopolitics and the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area” E-International Relations, 20 February 2018, https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/20/antarctic-geopolitics-and-the-ross-sea-marine-protected-area/.

[18] See for example Andrew Darby, “China’s Antarctica Satellite Base Plans Spark Concerns”, The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November 2014, https://www.smh.com.au/world/chinas-antarctica-satellite-base-plans-spark-concerns-20141112-11l3wx.html.

[19] For a discussion of what might constitute militarisation in Antarctica, see Jenna Higgins, “The Delineation of Militarisation in Antarctica”, RealClearDefense, 30 January 2017. Higgins believes that Antarctica has been militarised, but her idea of “militarisation has occurred when an adversary has the sole aim of causing military effect in war” is useful and by some readings actually implies that Antarctica has not been militarised,

[20] For a clear discussion of how military technology can be legitimately used in Antarctica, see Tony Press, “Australia Wants to Install Military Technology in Antarctica — Here’s Why That’s Allowed”, The Conversation, 23 August 2019, https://theconversation.com/australia-wants-to-install-military-technology-in-antarctica-heres-why-thats-allowed-122122.

[21] Anne-Marie Brady, China’s Expanding Antarctic Interests: Implications for Australia, Australian Strategic Policy Institute Special Report, August 2017, 17, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/chinas-expanding-interests-antarctica.

[22] See also the use of ground stations at McMurdo and Queen Maude Land for downloading from polar orbit satellites for weather observation by the civil US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, “How a Polar Satellite Sees the World”, Raytheon Intelligence and Space, undated, https://www.raytheonintelligenceandspace.com/news/feature/how-polar-satellite-sees-world.

[23] Claire Young, “What’s China Up to in Antarctica?”, The Strategist, 20 September 2018, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/whats-china-up-to-in-antarctica/.

[24] Anne-Marie Brady, China’s Expanding Antarctic Interests: Implications for New Zealand, Canterbury University Small States and the New Security Environment Research Project, Policy Brief No 2, 3 June 2017, 12, https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/media/documents/research/China's-expanding-Antarctic-interests.pdf.

[25] Pavel Velkovsky, Janani Mohan, and Maxwell Simon, “Satellite Jamming”, Issues Briefs — Tech Primer, On the Radar, 3 April 2019, https://ontheradar.csis.org/issue-briefs/satellite-jamming/.

[26] Dome A is the highest point in East Antarctica, and within Australia’s claimed territory: see Australian Antarctic Program, “Dome Argus”, https://www.antarctica.gov.au/antarctic-operations/stations/other-locations/dome-a/.

[27] See for example Eric Adams, “How to Track and Photograph Secret Spacecraft — The Gear and Skills You Need to Capture Elusive Craft in Action”, Popular Mechanics, 10 November 2019, https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/telescopes/a29739163/track-photograph-spacecraft-satellites/; and Leonard David, “How Amateur Satellite Trackers are Keeping an ‘Eye’ on Objects around the Earth”, Space.com, 3 May 2020, https://www.space.com/amateur-satellite-trackers-on-global-lookout.html.

[28] Robert Perkins and Rosemary Griffin, “Russia Stokes Political Tensions with Hunt for Antarctic Oil”,

S&P Global Platts, Natural Gas and Oil, 21 February 2020, https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/022120-russia-stokes-political-tensions-with-hunt-for-antarctic-oil.

[29] Although Russia’s polar expeditions have sometimes used the language of ‘prospecting’, Russian diplomats have denied this, stating that “Following the Antarctic Treaty System requirements no geological surveyance works are performed by Russia in Antarctica” in the [Canberra] Embassy of the Russian Federation’s Submission to the Enquiry of Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories into the Adequacy of Australia’s Infrastructure Assets and Capability in Antarctica, https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=22fef8c7-76b9-4acf-869e-79fc5e6c7177&subId=515982.

[30] “China Dives into Deep-Sea Mining”, The Maritime Executive, 29 March 2019, https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/china-dives-into-deep-sea-mining.

[31] Elizabeth Buchanan, “The (Other) Continent We Can’t Defend”, The Interpreter, 13 August 2019, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/other-continent-we-can-t-defend.

[32] See the discussion of China’s arguments over whether CCAMLR objectives allow for the establishment of MPAs in Danielle Smith and Julia Jabour, “MPAs in ABNJ: Lessons from Two High Seas Regimes”, ICES Journal of Marine Science, Vol 75, Issue 1, Jan/Feb 2018, https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/75/1/417/4430996?login=true; see also Zhang Gaoli, “Adhere to the Principle and Spirit of the Antarctic Treaty to Better Understand, Protect and Utilize the Antarctica”, 23 April 2017, http://belfast.china-consulate.org/eng/zgxw_1/t1465158.htm.

[33] Report of the 38th Meeting of the Commission, Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, November 2019, paragraphs 3.22–3.48, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/system/files/e-cc-38_1.pdf.

[34] Anne Applebaum, “How China Outsmarted the Trump Administration”, The Atlantic, November 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/11/trump-who-withdrawal-china/616475/.

[35] Anna Gross and Madhumita Murgia, “China and Huawei Propose Reinvention of the Internet”, Financial Times, 28 March 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/c78be2cf-a1a1-40b1-8ab7-904d7095e0f2.

[36] See for example paragraphs 6.28–6.74 in Report of the 38th Meeting of the Commission, Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, November 2019, which includes an outburst from the Argentinian representative that “the adoption of RMPs [research and management plans] has gained greater weight than the MPA objectives themselves”, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/meetings/26.

[37] Hence Australia’s request that the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf delay examining Australia’s data on the AAT shelf to avoid upsetting the Treaty’s freezing of arguments over claims. For a short, clear discussion of the history of the relationship between the ATS and other international maritime agreements, see Karen Scott, “Antarctic Resources in 2050: Regime Complexity and Regime Resilience”, Antarctica 2050: Strategic Challenges and Responses, Australian Civil-Military Centre, 23–27, https://www.acmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-04/Antarctica%20Booklet%20Final%2020200221.pdf; see also Linda A Malone, “The Waters of Antarctica: Do They Belong to Some States, No States, or All States?”, William and Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review, Vol 43, Issue 1, 2018, https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol43/iss1/3/.

[38] Mark Godfrey, “China’s Demand for Krill May Result in Changes to CCAMLR Convention”, SeafoodSource, 27 November 2019, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/chinas-demand-for-krill-may-result-in-changes-to-ccamlr-convention.

[39] See for example paragraphs 6.15–6.24 for Russia and China taking similar stances on the adoption of MPAs, in Report of the 38th Meeting of the Commission, Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, November 2019. https://www.ccamlr.org/en/meetings/26.

[40] Preliminary Report of the 39th Meeting of the Commission, Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, 2020, paragraphs 3.2–3.19 https://www.ccamlr.org/en/meetings/26.

[41] Natalia A Ramos Miranda, “Chile Keeps Eye on Chinese Fishing Fleet along South American Coast”, Reuters, 9 October 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-fishing-china-idUSKBN26T3IL.

[42] Mark Godfrey, “Argentine Coast Guard Opens Fire on Chinese Fishing Vessel”, SeafoodSource, 4 March 2019, https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/argentine-coast-guard-opens-fire-on-chinese-fishing-vessel.

[43] “Environmental Affairs Fines Chinese Fishing Trawlers for Being on South African Waters”, Press Release, South African Government, 26 April 2020, https://www.gov.za/speeches/environmental-affairs-fines-chinese-fishing-trawlers-being-south-african-waters-26-apr-2020.

[44] Tim Stephens, “Australia and the United States in Antarctica: Warm Partners on the Coldest Continent”, United States Studies Centre, 6 December 2016, https://www.ussc.edu.au/analysis/australia-and-the-united-states-in-antarctica-warm-partners-on-the-coldest-continent.

[45] Anne-Marie Brady, “A Pyrrhic Victory in Antarctica?”, The Diplomat, 4 November 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/11/a-pyrrhic-victory-in-antarctica/.

[46] Claire Marshall, “Krill Companies Limit Antarctic Fishing”, BBC News, 9 July 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-44771943.

[47] AJ Press, 20 Year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan, Australian Antarctic Division, July 20, http://www.antarctica.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/178595/20-Year-Plan_Press-Report.pdf.

[48] Grant Wyeth, “The Worrying Geopolitical Implications of Australia’s Antarctic Airport Plan”, The Diplomat, 6 January 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/01/the-worrying-geopolitical-implications-of-australias-antarctic-airport-plan/.

[49] Chen Ziyan, “China to Build its First Permanent Airfield in Antarctica”, China Daily.com.cn, Global Edition, 12 October 2018, http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201810/29/WS5bd66044a310eff303285121.html.

[50] Preliminary Report of the 39th Meeting of the Commission, Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, 2020, paragraph 3.14, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/system/files/e-cc-39-prelim-v1.2.pdf.

[51] Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan, Australian Antarctic Program, https://www.antarctica.gov.au/science/australian-antarctic-science-strategic-plan/.

[52] See Box 3.

[53] China’s proposal for an Antarctic Specially Managed Area (ASMA) for Dome A, which would have given China the right to be notified before other states entered, has been rejected by Treaty meetings because ASMAs are for co-located stations of different states; see Nengye Liu, “The Heights of China’s Ambition in Antarctica”, The Interpreter, 11 July 2019, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/heights-china-s-ambition-antarctica. Australia also rejected China’s compromise Code of Conduct because such codes are intended for joint projects, but Beijing likely interpreted the rejection as a defence of our sovereignty, see Jackson Gothe-Snape, “Australia Declares China’s Plan for Antarctic Conduct Has ‘No Formal Standing’”, ABC News, 30 July 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-30/antarctica-china-code-of-conduct-dome-a/11318646?nw=0.

[54] Richard Norton-Taylor, “Destroyers Will Break Down If Sent to Middle East, Admits Royal Navy”, The Guardian, 8 June 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jun/07/destroyers-will-break-down-if-sent-to-middle-east-admits-royal-navy.

[55] New Zealand Ministry of Defence, “Southern Ocean Patrol Vessel”, https://www.defence.govt.nz/what-we-do/delivering-defence-capability/defence-capability-projects/southern-ocean-patrol-vessel/.

[56] H I Sutton, “China Builds Surveillance Network in South China Sea”, Forbes, 5 August 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/hisutton/2020/08/05/china-builds-surveillance-network-in-international-waters-of-south-china-sea/?sh=6a7f806174f3.

[57] Michael Shoebridge, “Chinese Espionage in Australia — The Big Picture”, The Strategist, 26 November 2019, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/chinese-espionage-in-australia-the-big-picture/.