For years, Chinese television dramas were the poor cousins of Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese soap operas. A 2018 Chinese remake of the Taiwanese show Meteor Garden is a good example. Following the tensions between a poor girl and four rich boys, the mainland version was unwatchable. A drama about class divisions set in present-day China – where class divisions aren’t up for discussion – was never going to work.

Yet just a year later, Chinese TV hit on the secret sauce: take out the women, set it in a fantasy world, and ramp up the sexual tension between the boys.

Boys’ love, or BL, is the new black, and Chinese audiences and readers can’t get enough of it. While a decade ago this genre was bubbling away in the quietest corners of the Chinese internet, a series of hit online and TV dramas mean BL is now big business.

Boys’ love isn’t new, dating back to 1960s fan fiction that saw Captain Kirk and Doctor Spock finally acting on the sexual tension between the characters portrayed by William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy. It’s a genre that’s still going strong.

Known as danmei (耽美 – indulging beauty) in Chinese, the tradition has strong roots in Korea and Japan. While the writing feels thoroughly queer, there’s a twist. Boys’ love is largely written by women, for women, and has little connection to gay fiction and even less with the often-grim reality of gay life in China.

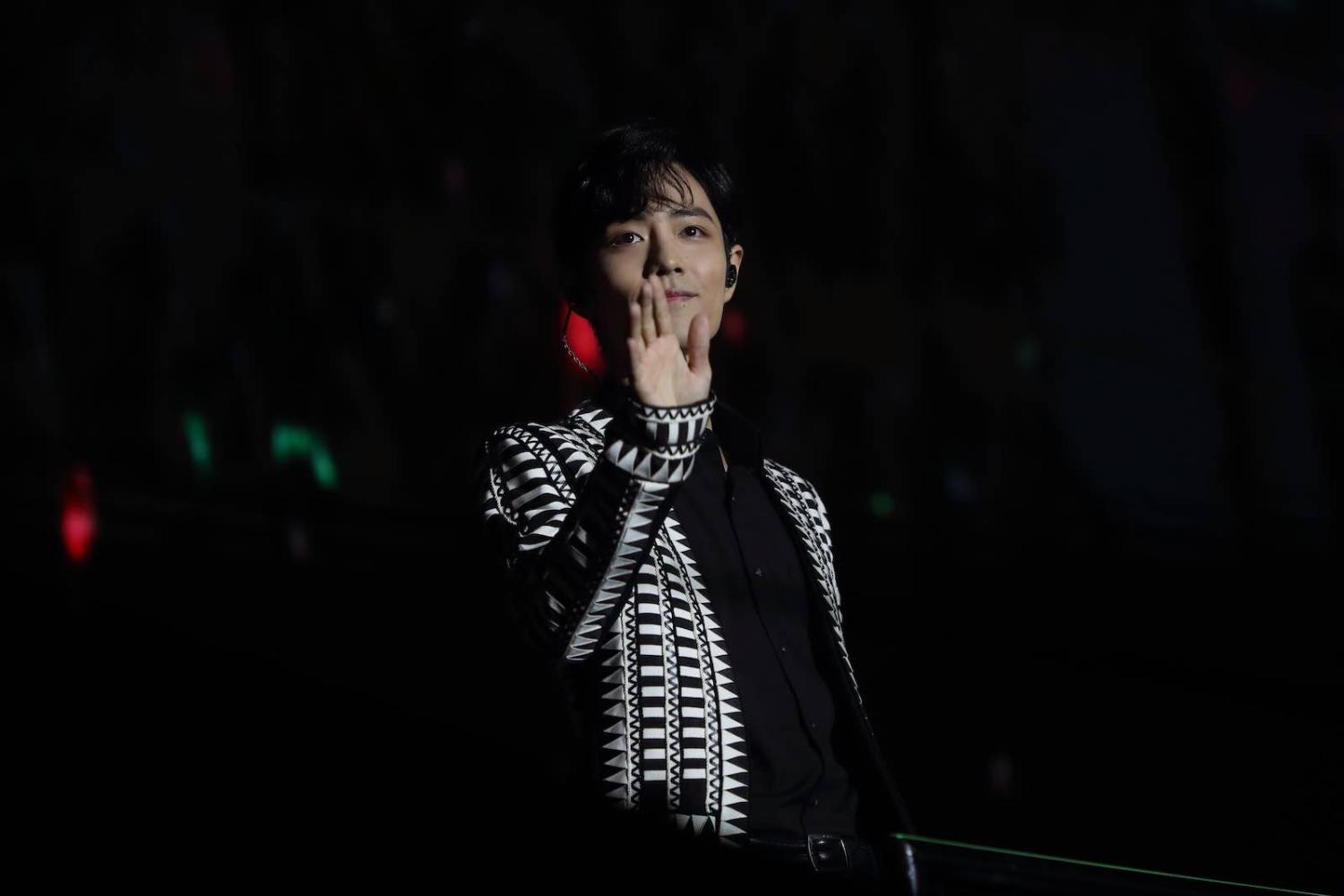

The show most responsible for bringing BL into the mainstream is The Untamed, a fantasy epic adapted from the most popular BL novel in China, The Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (Mo Dao Zu Shi, 魔道祖师). Produced by Tencent and screening on Netflix, it stars Xiao Zhan as the mischievous Wei Wuxian and Wang Yibo as the rather stiff Lan Zhan. Both actors are unfeasibly beautiful.

The original book (available in translation) is unmistakably spicy. The TV series, which had to navigate the Chinese censorship regime, stays on the side of what Hong Kong University academic Angie Baecker describes as “plausible deniability”. Unlike the book, there’s no scope for the protagonists to kiss, get married or break a bathtub, but there are lingering glances, rabbits bumping noses for no particular reason (rabbit is slang for a gay man), and even a brief glimpse of a gay graphic novel.

The Untamed is thoroughly addictive, creating a world filled with gorgeous sets and costumes where women are largely absent, and nearly all the characters can be read as gay men. If Wei Wuxian and Lan Zhan aren’t your cup of tea, there are other couples to choose from. Heterosexual relations, where they appear, are doomed, nasty or perfunctory.

BL might have remained under the radar, except for an accidental collision between the enormous fan base of the actor Xiao Zhan and the much more niche BL fan fiction universe. Much of Chinese BL fiction was hosted on the New York–based site Archive of Our Own (AO3), or at least it was until late February last year, when fans of Xiao Zhan objected to a story that transformed the actor into a transgender prostitute with a penchant for teenage boys.

China’s censors aren’t shy about banning entire genres when the CCP decides the line has been crossed.

A subgroup of Xiao Zhan’s fans reported the site to authorities, flagging it as “pornographic” content. The censors took the crude approach of blocking AO3 and China-based Lofter, disenfranchising a huge set of writers and their fans.

The backlash against the actor was immediate, with fans of the sites targeting both the celebrity and the vast suite of brands he endorsed, from Olay to Zwilling knives. Xiao Zhan, who had endured fans trapping him in a revolving door and even changing his flights, now faced relentless online attacks, ironically brought on by his own fans. The pressure was such that Xiao Zhan did an apology interview (which garnered more than 1 billion views), before following the tried and tested rehabilitation formula of patriotic songs and charity work.

Where BL drama will go now seems unclear. Censorship of explicitly sexual content has been tightening under the macho stewardship of Xi Jinping, who famously observed that the Soviet Union collapsed because while its communist party had proportionally more members than the Chinese Communist Party, “nobody was man enough to stand up and resist”. Core socialist values, which are the centre of Xi’s ideology, are writing neo-Confucian ideals of gender relations into China’s legal code.

China’s censors aren’t shy about banning entire genres when the CCP decides the line has been crossed – time-travel dramas have been off the menu for some time. Set against this are commercial realities. Chinese audiences, particularly women, want to see BL characters and storylines. For all the trials faced by Xiao Zhan in 2020, his celebrity was built on a BL drama. And BL ticks the soft-power box that forever eludes the CCP. The Untamed is huge in Asia, with fans in Thailand usually rated as the most dedicated.

Speaking with us on The Little Red Podcast, a BL author writing under the pen name Huanxiang Zhenghuanzhe (幻想症患者 – sufferer of fantasy) offered this telling prediction:

BL will split between a commercial space where the BL storylines are trying to get into all these TV dramas, into these web series, and get more voice in the public forum. The other space, more niche, pure fan fiction with a smaller audience, in here we’re still trying to push a lot of boundaries. That will still exist, but I do see a trend in China for that space to shrink. The last thing I want to see is the commercial space eat[ing] into this niche market. Instead of having a more positive influence, they fight over each other, and finally censorship kicks in and kills everything.

This article draws from the “Fandom Untamed: The Business of Boys’ Love” episode of The Little Red Podcast, which features interviews and chat celebrating China beyond the Beijing beltway.