1. The 'rules-based' euphemism

The term 'rules-based' is repeated 56 times throughout the 2016 Defence White Paper. Short-form for 'Australia prefers the status quo', the term 'rules-based' is an expression of fear and uncertainty, given that the status quo is being challenged.

At the time of the 1976 Defence White Paper, for instance, Australia's strategic environment could not have been more different. Back then our major strategic and trade partners were the same, the Soviet Union and China were implacable foes, while the economic and technological gap separating the West and Asia was widening. Today, in every respect, the opposite is true.

The repeated exhortation to preserve the 'rules-based' order is therefore an admission of this epochal strategic shift. The US-led order that has underpinned strategic stability in Asia over the past 40 years is fast disintegrating. We are entering a new era of strategic uncertainty characterised by intense great-power rivalry and challenges to international norms with which Australia is long accustomed.

2. The American sunset

For the first time the 2016 Defence White Paper leaves open the prospect of an end to US primacy in the Western Pacific.

Paragraph 2.8 states that 'the US will remain the pre-eminent global military power for the next two decades'. In geo-strategic terms, 20 years is the blink of an eye, and previous Defence White Papers have prophesised US military preponderance for 'the foreseeable future'.

One might argue that the 2016 Defence White Paper is merely providing a strategic outlook on a twenty-year timescale, and that it should not be inferred by this statement that the Australian government believes US primacy in the Western Pacific may end. However, paragraph 2.35 offers a startling projection of regional military expenditures to 2035, when China has clearly eclipsed the US. Its inclusion in the Defence White Paper is significant.

Moreover, it must be recognised that the US has global security interests (I would say distractions), while China concentrates its force modernisation on a comparatively narrow range of strategic objectives. China does so at a fraction of the cost of the US, and without the handicap of having to project power across 10,000km of Pacific Ocean. [fold]

In other words, the 2016 Defence White Paper is clear: the 'rules-based order' is being challenged, and perpetual American primacy cannot be guaranteed.

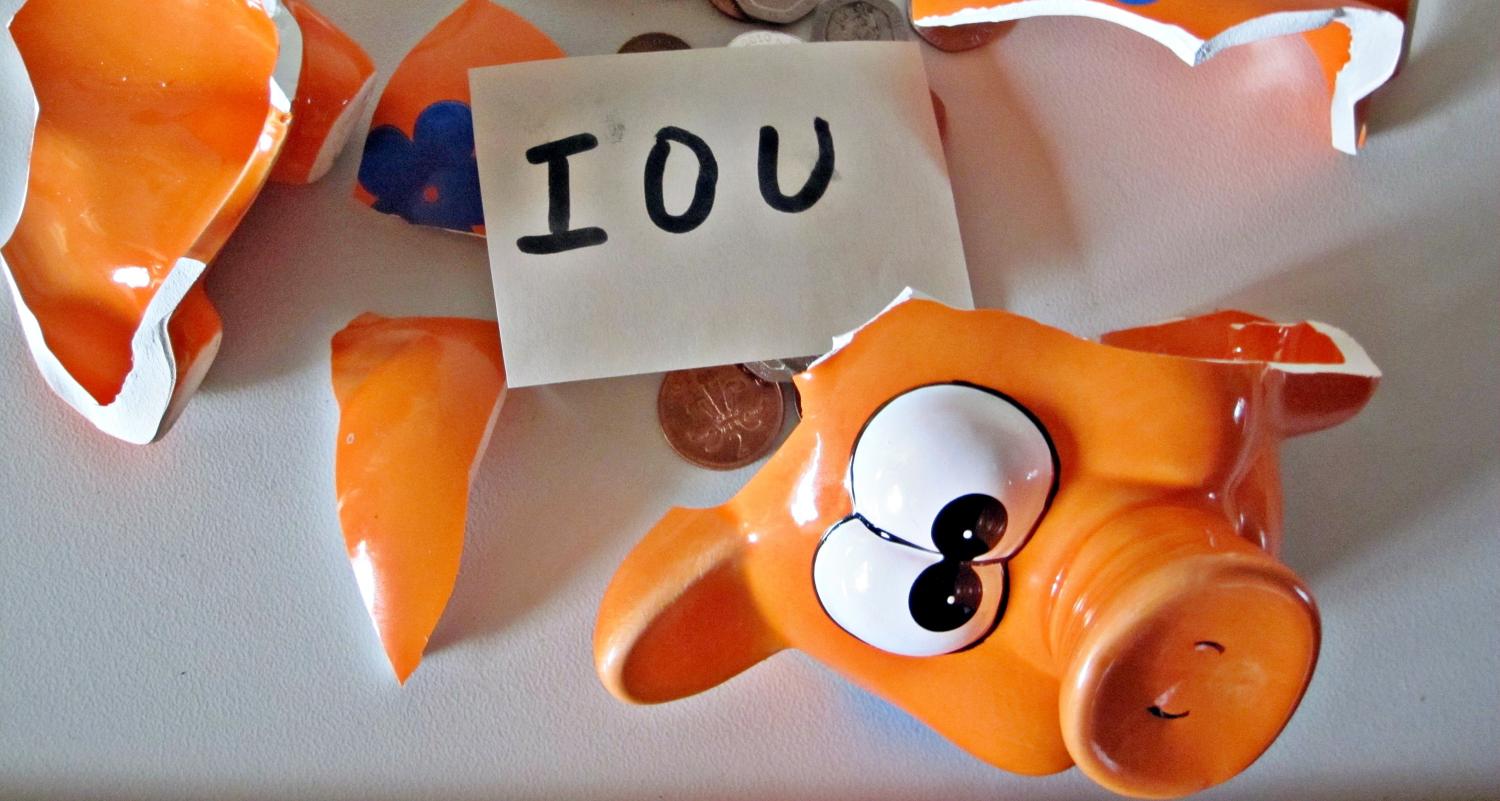

3. The commitment to spending 2% of GDP on defence

On seven occasions throughout the new Defence White Paper, the commitment to spending 2% of GDP on defence is categorically affirmed. I've debated here on The Interpreter why the 2% target is essential for alliance management, and how this is quite unrelated to force planning.

Some longstanding opponents are writing contorted obituaries for the 2% target based on paragraph 8.10, which says the 'Government's 10 year funding model will not be subject to any further adjustments as a result of changes in Australia's GDP growth estimates'.

But all that's being asserted here is that the funding certainty provided in the Defence White Paper obviates any need to adjust force structure plans. The bottom line is the commitment to reaching the 2% target as a proportion of GDP is consistently and explicitly repeated throughout the document, including in the paragraphs that surround this quote. There is no prospect of the 2% of GDP target being jettisoned by any either major political party any time soon, and this is entirely consistent with Australia's national interests.

4. Australian defence policy is entering a pro-nuclear era

Defence white papers in recent history have affirmed Australia's longstanding commitment to nuclear disarmament and a nuclear-weapons-free world. References to Australia's reliance on US extended nuclear deterrence were couched in terms of 'so long as these weapons exist'.

That's now over. Paragraph 5.20 reads 'only the nuclear and conventional military capabilities of the US can offer effective deterrence against the possibility of nuclear threats against Australia.' Further, Paragraph 2.104 notes that Australia has 'historically' been a prominent supporter of the Non-Proliferation Treaty — a telling use of tense.

In light of deepening tensions in the Western Pacific and the proliferation of ballistic missiles among several countries listed in the Defence White Paper, it's clear that the Australian government's approach to nuclear weapons is fast evolving. Greater Australian reliance on nuclear deterrence capability is being foreshadowed.

5. The fall of Jakarta

When it comes to Indonesia, the 2016 Defence White Paper adopts a small-target approach. Granted, paragraph 5.34 labels a strong and productive relationship with Indonesia as 'critical to our national security'. Yet this reads more as a factual statement than an ambition for deepening our defence partnership.

The 2013 Defence White Paper, by contrast, saw great opportunity in maturing the Australia–Indonesia defence relationship. It recognised that Indonesia was a major land power stranded on a massive archipelago, and that our asymmetric force posture is conducive to a comprehensive defence partnership that could multiply the strategic weight of both countries. Since then, circumstances have dramatically altered. Spying revelations, naval violations of Indonesian waters, bribing of people smugglers, and the execution of two reformed Australian prisoners have seen relations sink to their lowest ebb since the East Timor crisis of 1999.

The 2016 Defence White Paper provides a shopping list of ongoing bilateral defence activities and recognises the strategic implications of Indonesia's rise. Yet it presents no plan for getting ahead of this curve or realising the long term potential of Australia-Indonesia defence cooperation. Given the relationship's importance, the failure of the 2016 Defence White Paper to provide a credible and ambitious strategic blueprint for bilateral defence cooperation is a major weakness.

6. The curious equivalency of the Strategic Defence Objectives

The 2016 Defence White Paper lists three so-called 'Strategic Defence Objectives'. These are:

- Deter, deny and defeat attacks on or threats to Australia and its national interests, and northern approaches.

- Make effective military contributions to support the security of maritime South East Asia and support the governments of Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste and of Pacific Island Countries to build and strengthen their security.

- Contribute military capabilities to coalition operations that support Australia's interests in a rules-based global order.

At first read, these objectives are long-standing and uncontroversial. What is profound, however, is that paragraph 3.10 stipulates that the Government agrees these should be 'equally weighted' – a remarkably ham-fisted assertion.

Imagine Australia is being invaded by a foreign power through its northern approaches. Meanwhile, an allied request is made for an Australian contingent to help stabilise a region in the Middle East. Which should be the higher priority for the Australian government? The 2016 Defence White Paper's failure to clarify the order of Australia's strategic priorities represents a clear flaw.

7. The absence of the Anglosphere

In many ways the 2016 Defence White Paper released under Malcolm Turnbull and Marise Payne bears close resemblance to what might have been expected under their immediate predecessors. One imagines, however, that a Defence White Paper released under a prime minister who reintroduced knights and dames would have more to say about our colonial devotion to the mother country.

As it is, the Defence White Paper offers little more than a polite nod to Australia's historical ties with the UK, and presents a factual account of ongoing security and intelligence linkages in a couple paragraphs. The same is true for Canada. In other words, the Defence White Paper gives attention to the UK commensurate with its influence in our strategic affairs: marginal.

8. The 'newly powerful' folly

The most explicit paragraph on China is one that doesn't refer to it by name. Paragraph 2.24 reads:

While it is natural for newly powerful countries to seek greater influence, they also have a responsibility to act in a way that constructively contributes to global stability, security and prosperity. However, some countries and non-state actors have sought to challenge the rules that govern actions in the global commons such as the high seas, cyberspace and space in some unhelpful ways, leading to uncertainty and tension.

Of course this is a not-so-subtle reference to China's dredging and militarising of artificial islands in the South China Sea, industrial scale cyber theft, and weaponisation of space.

But to frame thinking about China as 'newly powerful' is to commit the very gravest error, one that could lead to catastrophic miscalculation when assessing China's resolve. For the Chinese, theirs is the greatest civilisation to have ever existed – the core of a Sino-centric world order lasting 1800 years. From Beijing's point of view, the dominance of Western powers is but a blip on the long annals of the Middle Kingdom, and China's rise is merely the natural correction to the rightful longstanding norm.

The implication of the 2016 Defence White Paper is that if China merely constrains its ambition and accepts the 'established rules-based order' as imposed by the more enlightened foreign powers, then peace and stability can prevail.

But herein lays the immutable truth about the great-power rivalry unfolding on Australia's doorstep: China views itself not as newly emerging, but as re-emerging. This means China's ambition is not based on grandiose fantasies but on reclaiming past glories and overcoming recent humiliations. That's a very different proposition to what the 'newly powerful' label so condescendingly implies.

Conclusion

I'll conclude this lengthy review by referencing the speech that Prime Minister Turnbull recently delivered to CSIS in Washington, where he noted President's Xi's expressed desire to avoid the 'Thucydides Trap'.

This is a reference to the tendency throughout history for conflict to erupt when an established power is faced with a rising power. In describing the cause of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides provides this timeless explanation: 'It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this inspired in Sparta that made war inevitable.'

Turnbull told his American audience that he believed President Xi's sincerity with regard to avoiding the Thucydides Trap, and that China should therefore refrain from provocations that might lead to conflict.

But what the Prime Minister failed to mention was that the Peloponnesian War broke out when the established power (Sparta) declared war on the rising power (Athens), not the other way around. Therefore, when President Xi speaks of avoiding the Thucydides trap, he wants America to peaceably give ground.

It is beyond question that the American-led global order has been unambiguously good for Australia and the world. The US has been a more restrained, universalist, and inclusive hegemon than any historical comparator. It is no accident the American era coincides with unprecedented advancements in every metric of human progress. But we must be honest with ourselves. China's determination to expel the US from Asia is absolute, and the 'established rules-based order' is coming to an end.

Photo by Flickr user Peter Miller.

Crispin Rovere