Preparations are proceeding in a businesslike way for the second of three possible independence referendums in New Caledonia, in 2020. Loyalists and independence groups are staking out their positions.

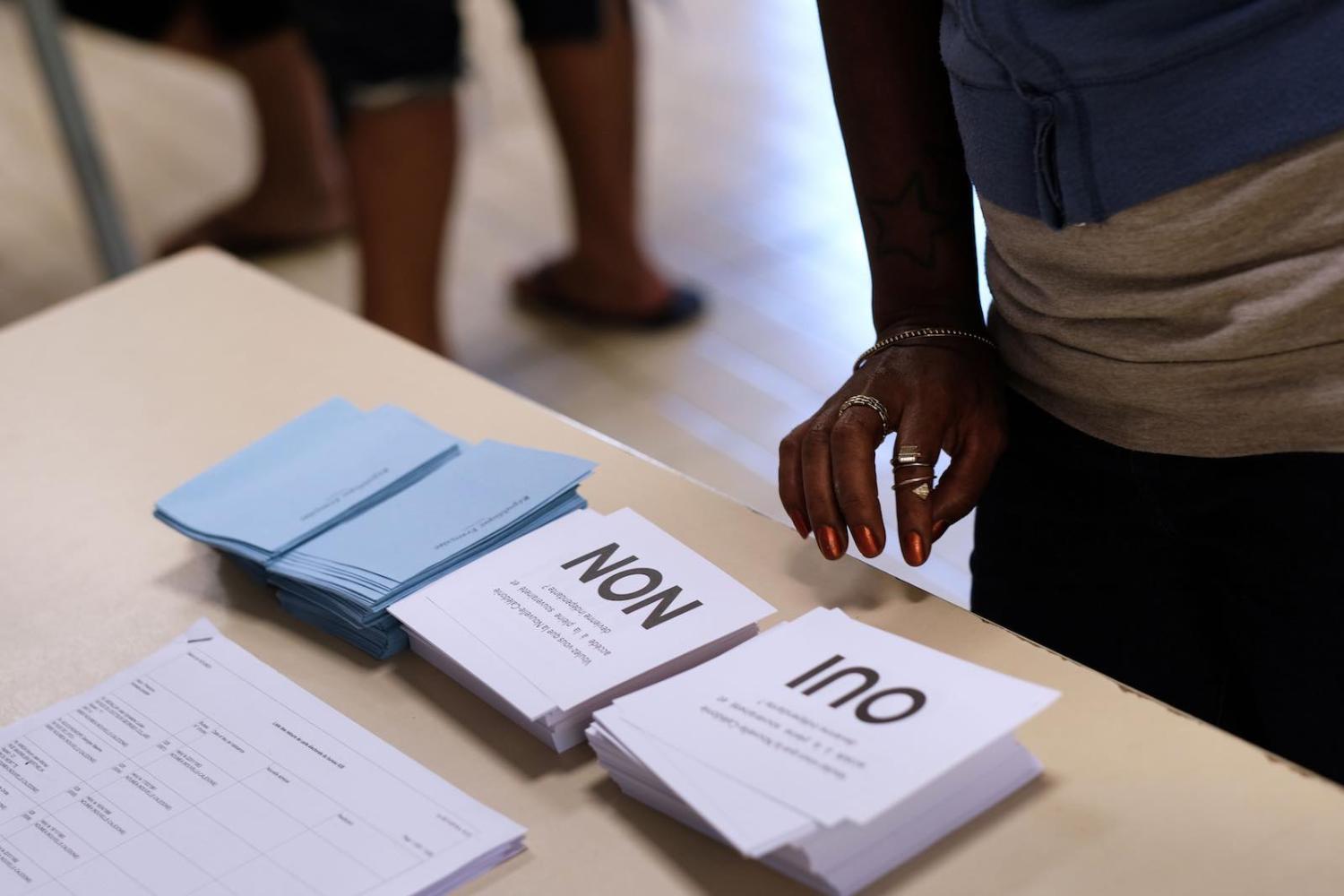

The Committee of Signatories of the 1998 Noumea Accord held its annual meeting in Paris on 10 October. The main issue was the date of any second independence referendum, which must be held by November 2020. Under agreements that have overseen 30 years of peace in Australia’s French near neighbour, and which are now ending, another two referendums are now likely, after voters rejected independence 57% to 43% in the first vote in November 2018. So long as the answer is no to independence, a further two votes can be held before 2022. Handling the processes is complicated by the fact that the “yes” to independence vote is relatively large and almost entirely indigenous Kanak, and thus cannot be ignored.

At the Committee meeting, after extensive debate and negotiation, French government, loyalist and independence participants agreed that the second of the three likely independence referendums will be held either on 30 August or 6 September 2020 (the final date is to be announced shortly, after a technical detail is sorted), on a similar basis to the first peaceful referendum of November 2018. Any third referendum would be timed before September 2021 or after August 2022 to avoid coinciding with French national elections. The meeting, while largely uneventful, did raise a few markers worth watching.

A key issue to watch is the endorsement of a more extensive background paper informing voters on the pros and cons of a “yes” or “no” vote.

The new main loyalist party, Avenir en Confiance (Future with Confidence) won its support at local Congress elections in April 2019 on a policy of holding the referendum as soon as possible, with an eye to restoring normal investment and economic development, much of which has been frozen during this uncertain period. Another loyalist concern backed by Paris is to complete these final votes before the French Presidential elections in April 2022, while the current French President is in power.

Such thinking is dubious, given that all recent presidents and national parties have and will continue to support the due implementation of the Noumea Accord. Still, there are better-founded concerns that it would be desirable for the referendums not to coincide with critical elements of the national French electoral cycle, such as presidential and legislative elections scheduled for April and June 2022, which has proven risky in the past. For example, a watershed development in New Caledonia was a 1988 skirmish at a cave which ended up a bloody massacre, largely because it occurred in the middle of two presidential election rounds, with the two main candidates, Chirac and Mitterrand, each approving heavy-handed tactics in their determination not to appear weak.

For their part, the independence parties preferred a second referendum as late as possible, around November 2020, to give themselves time to build on their support. Nonetheless, all independence leaders supported the compromise, just as loyalists accepted a compromise on a voter registration issue.

A subsidiary, but not new, difference was the abstention by the principal independence party, Union Calédonienne (Caledonian Union) from the meeting’s discussions on economic matters. Usually under this item, France rehearses its considerable economic support for its territory, representing a pointed reminder of the latter’s dependence on Paris. The UC claim that economic development is not for the Committee to discuss, as it is a responsibility of the local government.

This difference highlights the fundamental weakness of the Committee: its composition. It includes all significant political groups, which overweights the more divided loyalists, who have more parties. France, hardly impartial, also chairs the meetings. While the Committee does serve practical oversight needs, its agreements can sit oddly with the work of the Congress with its greater elected representation for the large independence parties, and can distort expectations amongst loyalist supporters.

This time, the UC leader, Rock Wamytan, an independence founding father, underlined the party’s dissatisfaction over discussion of economic matters by signing, on 12 October, an agreement with a prominent Corsican independence leader. Wamytan is known for drawing on support from independence groups within France and its external territories.

A key issue to watch is the meeting’s endorsement of a background paper informing voters on the pros and cons of a “yes” or “no” vote, more extensive for the 2020 referendum than that for the 2018 referendum. French law requires the French government to prepare such a paper before any referendum. In November 2018, contrary to some expectations, the French paper was short and uncontroversial. This time, preparation of the paper, involving all parties, may bring on more substantial and ultimately necessary discussion about the future shape of the territory, even under a persistent “no” vote.