What are the prospects of Australia meeting its Paris Accord commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 26-28% below the 2005 level by 2030? How we generate electricity will be key to meeting this target: electricity represents 35% of Australia’s emissions and provides the greatest opportunities for reduction. The Chief Scientist’s Preliminary Report on the National Electricity Market (NEM) says that existing policies won’t get us there. The political reaction to the report closes off the cost-efficient policy options explored in the report, narrowing the choice to either missing the targets or paying an unnecessarily high price to meet them.

The NEM is the longest geographically connected power system in the world, supplying the states and territories of eastern and southern Australia. The report has a wealth of fascinating information about the challenges of generating electricity while simultaneously finessing a 'trilemma': 'to ensure we have a secure electricity supply, at an affordable price for all Australian consumers, while meeting our international obligations to lower emissions'. The overwhelming message is that technology and the market are changing quickly: policy needs to seize the best options in a complex industry.

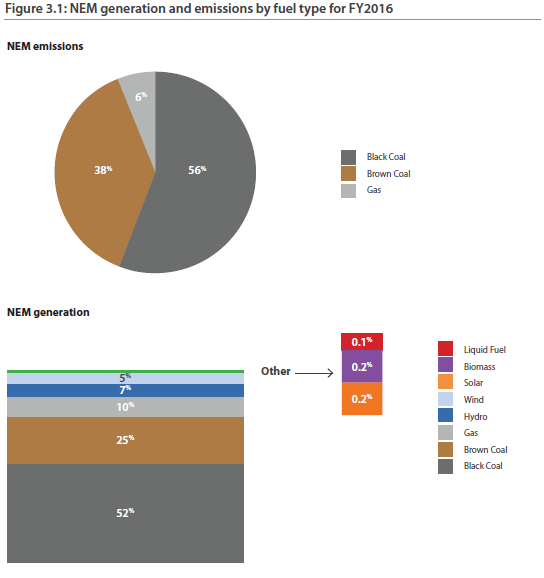

Australia already has a mix of market-based and direct-action schemes. The most relevant - the Renewable Energy Target – is losing its power to encourage investment. If Australia is to meet its domestically-set renewables target for 2020, it will have to double the renewable capacity installed since 2002. Investment in large-scale renewables, however, peaked in 2013. The current state of play is shown in the diagram below, reproduced from the Chief scientist's report.

The urgency for further action was highlighted by sharp price-spikes in South Australia’s wholesale electricity prices in July and August, followed by a total blackout in the whole of South Australia in September. The main cause was a weather event (strong winds) which destroyed transmission lines and triggered imbalances in supply. But SA’s high level of renewable energy generation (among the highest in the world) contributed to the problems.

This wasn’t the only unpleasant surprise in 2016. Tasmania had to install costly emissions-intensive diesel generating capacity when drought limited hydro power at a time when the Bass Strait transmission link was under repair. Adding to uncertainty, many existing coal-fired generators are old and no longer profitable in the current environment. Nine coal-fired generators have closed since 2012 and Victoria’s large emissions-intensive Hazelwood brown coal generators will close in March 2017. That is good news for lower emissions, but it threatens electricity supply-security at a time when investment is discouraged by policy uncertainty.

All this shows that reconciling the trilemma is an urgent task. The Report is preliminary and doesn’t offer specific recommendations. It is, however, clear on key components of the way forward. Renewables will need further longer-term incentives but, for technical reasons, renewables alone will not provide supply security in the foreseeable future. Gas-generation (still an emitter, but much less than coal) will have to play a bigger role, with tricky implications for gas supply.

The Report identifies three elements which, in combination, could address the trilemma:

- An emissions-intensity scheme. An emissions-intensity baseline would be set for the generating industry, with those operating above the baseline having to buy credits from those below.

- Extending the current Long-Range Renewable Energy Target (LRET) under which generators are required to buy emission credits from large-scale renewables generators.

- Regulated closure of emission-intensive generation (either with or without compensation to owners).

Asked by the Chief Scientist to evaluate these options, the Australian Energy Market Commission and Australian Energy Market Operator found that of the three policies:

An emission intensity scheme best integrated with the electricity market’s pricing and risk management framework, had the lowest economic costs and the lowest impact on electricity prices. AEMC and AEMO also found that an emissions intensity scheme had the least impact on system security whereas the extended LRET had the most [adverse] impact. …The regulated closure policy had a slightly higher economic cost than the emissions intensity scheme. However, the regulated closure policy had the largest impact on electricity prices.

A recent report of the Climate Change Authority draws the same broad conclusions.

When Josh Frydenberg, energy and environment minister, mentioned that an emissions-intensity scheme would be among the possibilities considered in next year’s policy review, he ran into political flack. Senator Bernadi described the emission-intensity scheme as 'a dumb idea'. The Prime Minister quickly ruled it out.

The question for Senator Bernadi is whether he accepts Australia’s Paris commitment (he is a member of the government which signed the Accord) and if so, how this can be achieved while meeting the other two objectives of supply-security and affordable cost.