Geopolitics in the Pacific Islands: Playing for advantage

Competition among development partners in the region needs to be harnessed to lift standards and development outcomes.

- Pacific Islands Countries are leveraging geopolitical rivalries to maximise their development options. But unmanaged competition for influence among key development partners can compromise good governance and privilege geopolitical posturing over local priorities.

- Australia, the United States, and other traditional donors can capitalise on areas of strength, such as social inclusion and regional and multilateral initiatives. Joint efforts along these lines and the pooling of resources would scale up impact and set higher accountability standards.

- Despite the risk that higher standards will open gaps for non-traditional donors with less burdensome criteria, there is much long-term value in traditional development partners collaborating in a “race to the top” in meeting the region’s needs.

Executive summary

Traditional donors — Australia, France, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States — now compete with China for geopolitical influence in the Pacific Islands. Pacific Islands leaders worry this competition could lead to militarisation or “strategic manipulation”. [1] Leaders are refusing to choose between major powers and are claiming to be “friends to all, enemies to none”. This allows Pacific Islands Countries (PICs) to leverage strategic competition for political and national advantage, as well as maximise aid.

But there are limits to the “friends to all” rhetoric — not all friends share compatible values or governance systems. Some PICs, such as the US Compact states and French territories, have associations that limit their security engagements. Others, such as Papua New Guinea, have a clear preference for traditional partners to assist with security. [2]

Australia and the United States rarely work with China in the region. Yet China’s presence is permanent, and guardrails are needed to deter the erosion of democratic institutions and improve accountability for aid projects.

Pacific regional leaders’ declarations repeatedly call for greater donor coordination and a stronger focus on local priorities. But PICs have few mechanisms to push donors to coordinate aid, and often lack political will to forego the economic benefits of competition. In some PICs, systemic corruption militates against stronger accountability. [3]

The challenge for traditional partners is to align with Pacific priorities and play to their own strengths without compromising strategic interests. They can do that independently, but regional and multilateral partnerships can achieve greater scale and impact, and respond to PICs’ desire for more cooperation and streamlined processes. Concerted regional actions also help set development norms, and raise standards for aid quality and accountability, but require shared goals and greater integration of administrative systems.

The desire for influence and project oversight means most aid is given bilaterally. However, regional initiatives can maximise “situations of strength” [4] among likeminded partners by increasing the reach of activities, reshaping critical institutions for development effectiveness, and bolstering regional frameworks based on shared values.

A push by traditional partners for higher aid standards via multilateral agencies can come at the expense of speed and ease of access to finances, which are often the primary selling points of Chinese and other non-traditional donors’ engagement. [5] The challenge is to streamline processes and tailor programs to the contexts of PICs, with the aim of achieving efficiencies and responsiveness. Offerings made by traditional donors should be sustainable and consistent with core shared values supportive of aid accountability and long-term Pacific prosperity and stability.

Introduction

We reaffirm that small island developing States remain a special case for sustainable development in view of their unique and particular vulnerabilities and that they remain constrained in meeting their goals in all three dimensions of sustainable development. We recognize the ownership and leadership of small island developing States in overcoming some of these challenges, but stress that in the absence of international cooperation, success will remain difficult.

— SAMOA Pathway, 2014 [6]

Growing strategic rivalry between China and traditional partners [7] in the Pacific can encourage the use of aid to gain diplomatic influence and achieve “strategic denial” [8] to prevent an adversary from gaining advantage. [9] But donor efforts to force PICs to choose between major powers risks alienating them. Pacific leaders worry that great power rivalry could lead to the militarisation of the region, subsume Pacific priorities under the geostrategic interests of others, and limit development resources for critical areas such as health, climate adaptation, and infrastructure.

The development needs of PICs exceed the assistance available. All help is welcome, including from China. So, PICs diversify and hedge relationships for maximum gain. Many Pacific Islands leaders also manipulate development partners for personal or political advantage, at times against public interests. Solomon Islands’ security and development agreements with China significantly increased development support but led to public riots, national divisions, and accusations of political gain. [10]

PICs are friends to as many as possible when it comes to trade, and look for opportunities to expand markets.

Competition for influence can therefore put good governance, transparency, and regional unity at risk. This has been evident on both sides — Chinese deals curry elite political favour, [11] and the rushed US-initiated Partners in the Blue Pacific mechanism has been criticised for undermining existing regional institutions. [12] China’s failed mid-2022 push to quickly strike a regional security deal breached regional processes and caused divisions. [13]

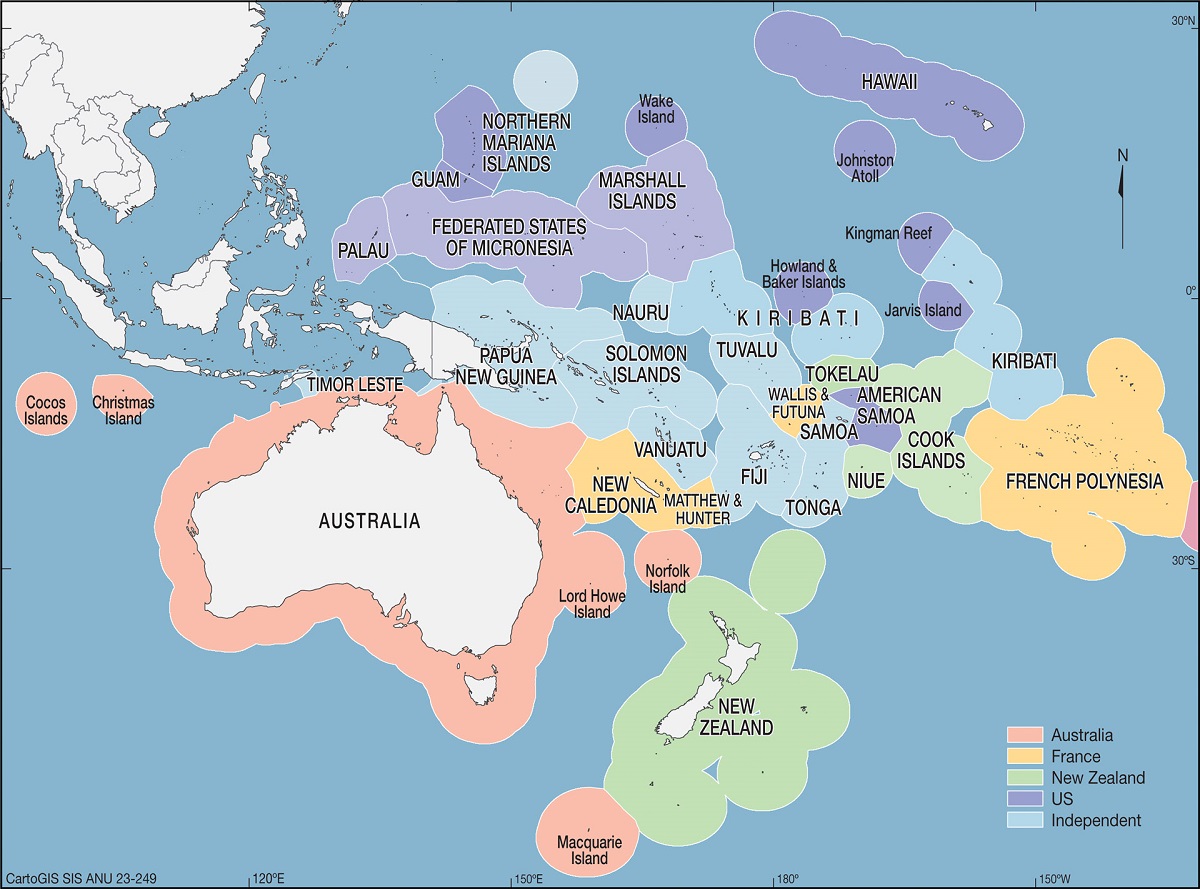

The oft-quoted PICs policy of remaining “friends to all, enemies to none” is challenging in practice, given the diversity of Pacific relations with outside powers (Figure 1). Some PICs, such as the US Compact states, have associations that limit their security engagements with others. Pacific Islands security forces work closely with traditional partners such as Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and France because of colonial history, common values and institutions, and sometimes binding security agreements. Others, such as Papua New Guinea, have a clear preference for traditional partners to assist with security. [14] Even so, China provides security training throughout the region.

PICs are friends to as many as possible when it comes to trade, and look for opportunities to expand markets. Solomon Islands is reliant on Chinese markets for commodity exports. Others, such as Fiji and Samoa, are more economically engaged with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. A few, such as Papua New Guinea (PNG), have strong export markets spread across geopolitical interests. All aim to expand trade and service delivery.

Figure 1: Pacific Islands Countries and the traditional partner relations

Global powers will continue to seek influence through bilateral aid, trade, and investment, and competition between donors is intense. However, traditional partners do not want competition to compromise accountability and good governance. Laws and values limit how much individual Western donors can compete with China’s fast, showy aid aimed at elite influence, visible infrastructure and resource access. China has little incentive to cooperate, and Australia and the United States have found few areas where cooperation with China is possible, or even welcome.

Australian Foreign Minister Senator Penny Wong has said in regard to China that Australia will “cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, … and vigorously pursue our own national interest”. [15] However, Wong’s vision of the alternatives may miss another option — to work with multilateral and regional bodies to raise the bar on development engagement and better respond to Pacific priorities. Can we increase the opportunities for Pacific recipients and Western donors to come together to build stronger Pacific-tailored and led regional institutions? Could these collaborations enhance reach and impact, improve alignment with PICs, and raise engagement standards?

Regional engagement and rule compliance are mostly optional and at times, national interests will be best served by building bilateral relations and gaining recognition through clear national branding.

Regional and multilateral agencies offer a space where diverse donors and recipients interact to achieve development goals and set regional norms. These institutions can, at their best, shape and lift development practice. For example, multilateral development banks (MDBs) provide a significant and growing source of finance. MDBs are incrementally introducing reforms to improve performance and accountability. Pacific regional agencies can also lift performance. For instance, the PIF Forum Fisheries Agency and work by The Pacific Community on regional tuna fisheries management significantly increase revenues and sustainability, and the Pacific Transnational Crime Network helps share data and combat crime.

Even so, regional agencies are not a panacea. Regional engagement and rule compliance are mostly optional and at times, national interests will be best served by building bilateral relations and gaining recognition through clear national branding. Collaboration costs can be considerable, so returns must also be high. Incentives to work regionally are strongest for large-scale, resource-intensive activities that benefit from pooling resources, expand technical assistance offerings, and reduce the administrative burden on Pacific countries. MDBs and regional agencies cannot dictate practices of sovereign countries, but they can set guardrails. [16]

This paper outlines the nature of current geopolitical competition and proposes regional and multilateral engagement initiatives that can both advance regional resilience and development, and meet Western strategic objectives. Regional cooperation is a powerful counterpart to bilateral efforts when goals are shared, systems complementary, and resources scarce. It is one tool of statecraft that can extend reach and influence in a region of intensifying geostrategic competition and growing development needs.

China's Pacific aid and development blueprint

China is ready to work with PICs to strengthen the confidence in tackling challenges together, build up consensus on jointly seeking development, form synergy for shaping the future together, and join hands to build an even closer China–PICs community with a shared future.

— Xi Jinping, President of China, 2022 [17]

Until 2018, Chinese activities among PICs only amounted to irritants to the regional ambitions of Australia and the United States. Measures to directly counter China’s influence were few.

But Chinese investment in the region hit record highs in 2016. And in the lead-up to the 2018 APEC (Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation) Leaders’ Meeting in Port Moresby, China Harbour Engineering Company secured a contract for the showpiece APEC Haus and associated road works, valued at more than US$4.5 billion. Australia and others provided substantial support for APEC, but that was less visible than the prominent Chinese buildings and roads. By the end of the APEC meeting, all eligible PICs had signed memoranda of understanding with China for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). [18] Australia and the United States felt their strategic influence ebbing; they stepped up competition and engagement.

There was considerable ground to make up. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2014 invitation to the People’s Republic of China’s “development express train” attracted many PICs. [19] Chinese infrastructure and resource development projects in the Pacific — from roads and wharves to parliament complexes and sports stadiums — are addressing investment gaps. Beijing’s diplomacy and finances are highly valued, and projects are often fast, visible, and much touted. In 2021, China was the fifth-largest bilateral donor, however its investments are targeted, mostly on infrastructure (Figure 2a) and resources, and neglect some priority areas such as climate resilience (Figure 2b).

Managing Chinese largesse and geopolitical competition is a challenge for Pacific statecraft. Chinese aid negotiations often bypass Pacific development ministries and go through prime ministerial offices or elite channels, raising concerns about the potential to erode government institutions. Solomon Islands’ MPs were allegedly offered more than AU$250,000 each to switch recognition from Taiwan to China, [20] raising public concerns about elite influence and corruption. [21] In the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in March 2023, outgoing President David Panuelo alleged Chinese actions were corrupting politicians, government decision-making, and regional agreements, aiming to align FSM with Beijing instead of Washington. [22]

The disruption of Covid-19, availability of other viable and cheaper sources of development finance, and worries about debt and the efficacy of the Belt and Road Initiative have resulted in a fall in Chinese loans to the region (Figure 3). [23] Recently, Samoa cancelled a US$100 million Chinese port upgrade project because of concerns over its debt servicing capacity. [24] In contrast, MDBs increased regional finances during the Covid-19 pandemic, with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) using direct budget support to boost liquidity during border closures (Figure 4). Lead donor, Australia, also increased finances and budget support (see next section).

Despite this changed post-Covid environment, Beijing will continue its efforts to expand trade and secure access to strategically important infrastructure, including ports and airfields. [25] Under the BRI and other initiatives, they will look for markets for Chinese green technology, access to resources such as minerals, gas, timber, and fish, and openings to expand economic and telecommunications integration. China is also trying to re-shape regional norms through engagement in Pacific Islands media and its global security and development initiatives. [26] The decline in Chinese aid does not translate into a decline in ambition or regional heft. Influence can exceed aid spending.

Chinese development assistance is adapting to maintain influence and respond to regional pressures, including through more grants, more local employment, and reportedly more attractive lending terms. [27] Chinese contractors look for investment openings and compete successfully for MDB contracts, often with lower bids than Western firms. Recently, Chinese firms have won contracts for critical infrastructure, including port upgrades in Nauru [28] and Solomon Islands. [29] Cost overruns, poor project quality, and concerns about limited local procurement, employment, and financial transparency have all been raised in relation to Chinese projects. [30]

The operating environment for Chinese state-owned enterprises in the Pacific can be challenging. China Harbour Engineering Company won the ADB Nauru port project but encountered delays and cost overruns. The Solomon Islands telecommunication tower project, involving a loan of about AU$100 million from China for 161 towers, also faces project delivery problems related to supplies and construction. [31] So far, very few towers have been built or are in operation. Weak capacity, corruption, and politicised procurement all militate against many PICs taking action to improve the quality and accountability of aid.

China is now facing more constrained financial times. Refinements to the BRI are evident in the recent shift to smaller projects targeted at areas where its geostrategic and economic interests are greatest. [32] Looking for regional work, Chinese state-owned enterprises will continue to bid for MDB finances. This is an opportunity for MDBs to strengthen their systems to ensure better value for money across all contractors by considering social, environmental, and economic issues, and assure that project quality and management controls are in place.

America and Australia respond

We [Australia] have a robust policy framework governing our approaches to China … It is partly defensive, yes, because China’s action requires it. But it is also proactive and open to a possible model of beneficial co-existence.

— Frances Adamson, Secretary of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2021

The United States, by its own admission, has paid insufficient attention to the Pacific Islands region in the last few decades. [34] The Obama administration’s pivot to the Asia-Pacific, announced in November 2011 and presented to Pacific Islands leaders in 2012 by then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, [35] had little impact. The United States appeared on track to reduce its financial commitments to Compact of Free Association (COFA) states — the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Palau, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands — until China’s rising influence in the region triggered a 2023 promise of US$7.1 billion over 20 years, trebling COFA offerings. [36]

Development funding and promises by traditional partners have increased, but coordinated engagement has fallen short. At the 2018 APEC leaders’ meeting in Port Moresby, the United States, with Australia, Japan, and New Zealand, committed to assist with supplying electricity to 70 per cent of PNG’s population by 2030, aiming to show Western resolve in delivering results together, and countering China. At the time, it was a rare display of multi-donor cooperation, [37] but the rushed announcement led to project design and coordination flaws, leaving the institutionally weak PNG Power to facilitate the complex project and Australia to do the heavy lifting.

As Chinese influence grew, the United States pursued more collaboration with PICs and with likeminded partners, but delivering has been difficult. The 2020 Pacific Pledge committed the United States to increase its development partnerships in the region. [38] Early in the Trump administration, the National Security Council created a position focused on Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific (a role formerly folded into East Asia) to boost performance. The Biden administration penned the first-ever Pacific Partnership Strategy to guide engagement and “coordinate with allies and partners — as well as with the Pacific Islands — to avoid redundancy and best meet the needs of the Pacific Islands”. [39]

Development funding and promises by traditional partners have increased, but coordinated engagement has fallen short.

A US–PIC summit convened by Washington in 2022 was backed by US$810 million in new funding over ten years, mostly targeting regional initiatives such as maritime security and climate resilience. [40] A further commitment of US$200 million was made at a 2023 summit, also focusing on regional engagement and strengthening regional institutions dealing with Pacific priority areas of resilience, disaster response, maritime security, and human development. All were positive initiatives but securing resources and supportive institutional arrangements has been slow. Congressional authorisations and appropriations are still awaiting action.

Delivering on financial commitments is critical, but there are other untapped opportunities. For example, the technical expertise of the United States in artificial intelligence and digital technology opens possibilities in maritime security to improve surveillance of valuable and vast ocean spaces. Western markets and education sectors are also attractive to PICs but remain hard to access. And the Partners in the Blue Pacific initiative has more untapped potential, as discussed later.

Australia has faced accusations of regional neglect, [41] but it invests more than any other donor to the Pacific Islands, including in regional institutions. In 2016, largely in response to record high levels of Chinese aid and growing influence, then Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced a “step change” in regional engagement to show long-term and enduring commitment and to “sharpen regional approaches”. [42] In 2018, then Prime Minister Scott Morrison unveiled the Pacific Step-up initiative, [43] which spanned security and development, including regional investments in security via the new Australia Pacific Security College and the Pacific Fusion Centre, and new funding for disaster resilience and digital connectivity. [44]

In a further move to address the huge infrastructure deficit in the region and offer an alternative to Chinese infrastructure loans, Australia established the Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP) in 2019. [45] This regional fund has AU$3 billion for infrastructure lending and another AU$1 billion for grants, and supports airports, sea cables, roads, ports, and renewable energy projects — about AU$1.2 billion has been committed across the Pacific. Australia is now the leading bilateral development partner for infrastructure investments in the region. The AIFFP provides an alternative to Chinese lending and sets regional standards for local procurement and accountability, but adds another financial mechanism to an already complex, crowded, and bureaucratic system.

The recently announced Australia–Tuvalu Falepili Union treaty signalled a shift in Australian regional engagement.

Australia has continued to increase funding and engagement in the region. Canberra announced an additional AU$900 million over four years (2022–26) in October 2022, and the 2023 May budget committed AU$1.9 billion to boost Pacific engagement, with AU$1.4 billion of that to enhance Pacific security. [46] Initiatives remain largely bilateral, but there are increasing commitments to multilateral action and regional institution reform to secure efficiencies and shape donor engagement. For example, recognising the value of regional cohesion and shared norms, Australia introduced the Pacific Quality Infrastructure Principles at the 2023 Pacific Islands Forum Economic Ministers’ Meeting. The aim is to raise the quality and sustainability of regional investment, including by China and other donors. [47]

The recently announced Australia–Tuvalu Falepili Union treaty signalled a shift in Australian regional engagement. The treaty creates a “special human mobility pathway” for up to 280 citizens annually from Tuvalu to live, work, and study in Australia. [48] It also provides security assistance to Tuvalu in response to natural disasters, public health emergencies, and military aggression. The catch is that Tuvalu must consult Australia on any security or defence-related engagement with other states, potentially creating a hurdle for future Chinese engagement. With an election due in early 2024, the Union and its implications for sovereignty will be publicly debated.

Similarly, the 2023 Australia–Papua New Guinea Bilateral Security Agreement and the Papua New Guinea–United States Defence Cooperation Agreement also create stronger security bonds. PNG Prime Minister James Marape has declared a clear preference for traditional partners to help provide security, but is keeping the trade and investment welcome mat out for China. [49] Geopolitical contestation will persist and need management to safeguard governance, sovereignty, and development prospects.

The costs of geopolitical competition

Despite some of the highest levels of per capita aid globally, PICs are off track to achieve most Sustainable Development Goals, [50] with a recent report noting “increasing vulnerabilities, deepening inequalities, and limited access to infrastructure and basic services”. [51] The ADB estimates the region has US$2.8 billion a year in unmet investment needs out to 2030, and at least an additional US$300 million per year is required for climate mitigation and adaptation. [52] Development partners are needed to help lift performance.

Geopolitical competition has led to record high development aid and loans to PICs (Figure 5). In some cases, this aid boosts critical infrastructure and services, but where accountability and transparency are weak, it can serve narrow political interests above development goals. [53] Increasingly, PICs are under debt distress and need more access to grants and highly concessional loans that address their vulnerabilities. Yet grants to the Pacific Islands are declining on a per capita basis. [54]

While there are many donors, some play outsized roles and shape development engagement. Australia leads development assistance in the region, while Japan, the United States, China, and New Zealand are among the top bilateral donors. Most aid is given bilaterally and not well coordinated regionally, though among likeminded partners there is more cooperation in areas such as infrastructure and telecommunications, where reaching scale and meeting high costs necessitates collaboration. Regionwide, MDBs are some of the few entities that attract participation from all key donor countries and streamline aid processes.

Managed well, multilateral platforms provide an opportunity for strategic dialogues among financers and recipients, and a means to raise standards of sustainability and accountability, but quality outcomes require robust systems to address concerns about value-for-money, recognition of contributions, and control over processes and outcomes. Some multilateral contracts have failed to deliver quality projects, or failed to advance local development and good governance.

Regardless of bilateral and regional capacity-building and support, security and development gaps will occur, creating opportunities for others.

Pacific regional entities such as the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and its associated agencies also play an important role as centres for coordination, information sharing, and norm setting. They benefit from traditional partner support to strengthen capacity, governance frameworks, and engagement approaches. The increased backing of the Pacific Regional Infrastructure Facility (PRIF) is an example of leveraging a regional agency to better align with Pacific priorities, as well as boost the capacity of PICs to strengthen their building codes, better manage projects, and implement National Infrastructure Investment Plans.

The downside of regional institutional arrangements is that they are rarely binding. In addition, regional agencies often lack resourcing even though they are uniquely placed to improve professional capacity and networks across the region, particularly for transnational issues. While engagement is time intensive and involves compromise, there are few other ways to align regional actions with regional policy, and build broad-based Pacific-wide values. For example, the Biketawa Declaration [55] strengthens regional security cooperation and framing, and promotes norms such as the “Pacific family first”, which underpins traditional partners as the “security partner[s] of choice” [56] for reasons of familiarity, interoperability, and continuity.

Yet, regardless of bilateral and regional capacity-building and support, security and development gaps will occur, creating opportunities for others. More partner funding alone will not solve the problem. What is needed is innovative engagement and partnerships that provide resources as well as strengthen regional and national institutions to deliver services and accountable governance, and sustain them over time.

The Pacific calls for cooperation

… development actors need to work with us, understand the politics of development in our region, and seek to engage with us in a way that supports our agency and leadership on sustainable development.

— The Hon Fiamē Naomi Mata’afa, Prime Minister of Samoa, 2023 [57]

Pacific leaders repeatedly call for more cooperation, noting that the geopolitical environment is becoming “crowded and complex”, uncoordinated, and often externally driven. [58] Pacific Islands leaders use regional declarations to call for donors to better coordinate efforts and align with Pacific Islands’ development goals (Figure 6), particularly in climate disaster management and resilience, regional security, and human development. In 2022, PIF leaders launched the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, [59] which explicitly calls for collaboration on key regional issues such as the economy, climate, and connectivity. But PICs need development partners to help put the words into action.

Regional cooperation on development and security issues can be difficult because there are few action-forcing mechanisms and some key development partners sit outside of regional agencies. [60] The PIF — the 18-member peak political body — only includes two donors: Australia and New Zealand. The PIF Post-Forum Dialogue engages 21 development partners, but is a cumbersome mechanism with no priority given to large, enduring partners over short-term ones. The current PIF regional architecture review could strengthen the Dialogue, regional institutional arrangements, and donor management, but needs more support.

Adding to regional fragmentation, development partners not in the PIF hold their own regional forums. Japan, South Korea, and others have regional meetings to engage PICs. China also has a regional forum, but it struggles to engage with existing regional institutions because three PIF members do not recognise the One-China principle.

New directions for regional collaboration

Regional diversity means a patchwork of arrangements will persist. Making progress can be challenging. The concerns raised by the 2009 Cairns Compact on Strengthening Development Coordination in the Pacific remain relevant: despite high levels of aid, the Pacific is “off track” on many development indicators, accountability is lacking, and best practices are not consistently followed. [61] Collaboration among rivals remains rare. For example, trilateral projects — one to combat malaria by Australia, China, and PNG, and another providing water services by New Zealand, China, and Cook Islands — struggled to reconcile operating styles, cultural contexts, and donor motivations. China claims it remains open to “tripartite cooperation in Pacific Island Countries” but there is little evidence of it. [62] It has not signed up to the Cairns Compact.

Yet, against this challenging backdrop, there is still scope for strengthening traditional donor collaboration, guardrails to underpin quality development, and regional agencies and initiatives.

Multilateral finance

As rivalries intensify, multilateral financing and regional partnerships offer an opportunity to pool resources, streamline access to funds, and strengthen regional networks. Not all will participate, but regional initiatives can raise standards and deter geopolitical competition from driving down quality. This is not only consistent with traditional donor interests, it also reflects Pacific priorities.

Since the pandemic, MDB investment in the region has greatly increased, now accounting for almost 20 per cent of all assistance. [63] This is good news for traditional donors — Australia, the United States, and Japan are significant contributors to the ADB and the World Bank, and have strong influence over the institutional reform agenda. ADB finance to the region jumped from US$568 million in 2015 to about US$1.34 billion in 2021. [64] World Bank lending grew six-fold from 2012 to 2022. [65] Their considerable finances provide a means to incentivise a “race to the top” among contractors and set expectations about accountability, localisation, and quality assurance — core issues that can be eroded by geopolitical competition.

The World Bank and the ADB have established processes to assess project needs, environmental and social safeguards, contractor suitability, and recipient financial capacity. The World Bank is strengthening its systems by introducing mandatory rated criteria to assess project cost, quality, socio-economic impacts, implementation capacity, and climate resilience. [66] Done well, such multidimensional criteria have applicability for donors and governments assessing projects at all levels. The challenge is to enhance quality outcomes without adding hurdles to access finances. In the words of the Tuvalu finance minister, “we need scale and speed”. [67] But the price of “speed” cannot be quality, transparency, or sustainability.

It is not just MDB internal processes that need strengthening. Ultimately, responsibility for “procurement, award, and administration of the contract … lies with the borrower”. [68] Managing procurement, contractor vetting, and contracts can be a burden for Pacific Islands governments with limited capacity and, in some instances, systems corrupted by elite interests. [69] MDBs could do more to boost technical capacity and provide independent project management support to ensure projects deliver the outcomes expected. Better country-based technical capacity is a recognised way of improving project and contract governance but often needs external support. [70]

The growth in MDB funds increases access to finance and can offer a more streamlined process across diverse donors. PICs often preference Chinese aid for its ease of access.

Initiatives such as the International Finance Corporation/World Bank Bina Harbour project in Solomon Islands and the World Bank Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative have technical support units embedded in government agencies to build capacity and ownership. The challenge for MDBs is to ensure technical capacity and local engagement are strengthened in a manner that creates the skills and institutional support for wider application. There will continue to be examples of political priorities trumping project management rigour, but without local capacity, system accountability will be weaker.

The 2017 ADB Procurement Policy [71] has increased transparency and quality assurance, but more can be done to support stronger environmental and project delivery safeguards, diversify contractors, and provide incentives to ensure local skill building, maintenance, and supply contracts. Current reforms to the ADB operating model will increase staff and expertise in the region, which should strengthen knowledge networks and allow greater flexibility. Stronger support of local and regional project oversight could ensure underbidding and poor performance are penalised and systems strengthened for future projects.

The growth in MDB funds increases access to finance and can offer a more streamlined process across diverse donors. PICs often preference Chinese aid for its ease of access. But for large-scale investments such as infrastructure and climate adaptation, MDBs can scale up available finances, simplify access, and extend reach. Collective expertise and institutional arrangements can also be leveraged. This is exemplified in Australia and New Zealand’s commitment to the PNG and the Pacific Islands Umbrella Facility run by the World Bank for health, education, and climate-resilient infrastructure. [72] For aid recipients, political priorities and the need to deliver quickly and cheaply will continue to affect choices about development engagements. For donors, bilateral engagement can be more effective than regional efforts at strengthening elite relations and raising the donor’s profile. But economic, climate, and debt pressures are growing in the region, [73] creating gaps in human development, and raising political stakes. With China reducing its quantum of loans and aid to the region, MDBs have an opportunity to better meet needs for highly concessional finance and grants by pooling funds and risks, and delivering tailored assistance that is responsive to vulnerabilities.

The climate crisis

Mobilizing adequate financing for sustainable development will be a challenge for all countries, but will be particularly difficult for Pacific Small Island Developing States where financing needs for sustainable, climate-sensitive development are estimated to be among the highest in the world … They are also set to rise with the predicted impacts of climate change.

— UNDP Discussion Paper, 2017 [74]

PICs identify climate change as their most significant security challenge, but global climate financing mechanisms have not met their targets. [75] PICs consistently call for more focused financial channels, additional resources, and compensation for climate loss and damage. They are pushing for greater global commitment as well as easier access to the Green Climate Fund [76] and the Global Environment Facility, which pool resources and streamline processes. Traditional donors play a key role in the initiation and management of these valued funds, and increasing their commitment to climate action is critical to their standing in the region.

Vulnerability to climate change, natural disasters, and economic shocks varies across the region, shaping the need for, and access to, development loans, grants, and concessional finance. Fiji, when PIF Chair, made the argument that climate-vulnerable small islands members should be classified as LDCs regardless of per capita income. [77] Such reclassification would raise equity challenges from vulnerable countries excluded by geography.

Another option is to assess vulnerability for all by applying the United Nations’ Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI) [78] and using it to adjust access to concessional funding for development programs. [79] This approach is supported by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and is the culmination of decades of advocacy to improve access to concessional finance. [80] The MVI may work in a broad development context, but if applied to a climate finance context could disadvantage PICs.

In theory, broad adoption of the MVI by MDBs and key donors could more consistently assess need for low-interest loans and grants according to an agreed set of criteria related to economic, environmental, social, structural, and climatic vulnerabilities. However, the MVI has flaws if specifically applied in the context of climate finance because strengths in some vulnerability categories, such as strong institutions, can outweigh climatic vulnerabilities. This reduces a country’s vulnerability ranking. [81] For example, Vanuatu, considered globally as one of the most climate-vulnerable countries (Figure 7a), ranks barely more than the world median vulnerability according to the MVI because other countries have higher levels of economic, social, and ecosystem vulnerability (Figure 7b).

Peter Ellis, Director of the Statistics for Development Division at The Pacific Community observed that “most Pacific countries (Nauru, Samoa, and Palau are the exceptions) are measured as more vulnerable on the current vulnerability measures [82] than they are on the MVI”. [83] This is concerning for access to climate finance. Traditional donors have the capacity and obligation to partner with PICs and regional agencies to ensure that fit-for-purpose assessment tools are used to allocate global climate finances, for example, drawing on tools tailored to assess climate vulnerability, such as the ND-GAIN vulnerability index. [84]

The Pacific is also acting to raise finance for climate resilience and is looking to development partners to support its efforts. The Pacific Resilience Facility [85] aims to secure US$1.5 billion to build resilience and disaster preparedness. The return on investment could be significant — $1 invested in resilience building saves $7 in post-disaster recovery. It will provide grants, not loans, potentially adding to debt. Partnerships are needed to raise capital and support efficient and accountable management. Australia and the United States have pledged support, but so far, funds have fallen short of the target — community and economic stability could be at stake. [86]

At COP28, ambition fell short of Pacific Islands’ needs and the Paris Agreement to keep global warming below 1.5°C of pre-industrial times.

PICs are also looking to development partners to mobilise more resources for development and resilience under regional “partnerships for prosperity” programs, and in particular the new Pacific Partnerships, Integration and Resource Mobilisation Office (PIRMO), which aspires to increase private sector and philanthropic funding. This is an area of strength and advantage for traditional donors, one where non-traditional donors rarely engage. These partnerships can further add to engagement scale and reach by diversifying people-to-people relationships. Research partnerships are also in demand to ensure efforts are efficient and effective — another area of traditional partner strength.

Given the existential threat of the climate crisis to Pacific Islands, collaboration across geopolitical divides is merited. In November 2023, China and the United States — the two largest greenhouse gas producers — recognised their joint responsibility to work “together cooperatively to address the goals of the Paris Agreement and promote multilateralism”. [87] Then, on 2 December, China, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates announced an additional US$1 billion in methane reduction grants. [88] These moves will not reverse the existential threat to PICs, but they signal a shift in the willingness of large greenhouse gas emitters to collaborate.

Even so, global commitment is inadequate from a PIC perspective. At COP28 — the annual UN global climate meeting, in 2023 held in Dubai — ambition fell short of Pacific Islands’ needs and the Paris Agreement to keep global warming below 1.5°C of pre-industrial times. [89] Although the Pacific Islands’ push for the loss and damage fund has been finalised and so far more than US$700 million has been pledged, the current commitments represent less than 0.2 per cent of the economic and non-economic losses faced by developing countries every year. [90] With so much demand, it is not clear if the Pacific Islands will benefit significantly from this fund. They will continue to rely heavily on regional and bilateral arrangements to respond to their growing needs for climate finance, adaptation, and mobility.

Not only do the pledged funds fall short, but the outcome of the agreed text in the UN’s Global Stocktake [91] on emissions reductions is also far from sufficient, especially for Pacific Islands. The final wording of the Global Stocktake was agreed without AOSIS present in the closing plenary. AOSIS, representing 39 countries, subsequently objected to the text, however, the decision was not re-opened. [92] For the PICs, this year’s COP is another missed opportunity for meaningful climate action. For Australia, hoping to jointly host the COP in 2026 with the Pacific Islands, there will be pressure to improve its own performance along with that of the global community.

Blue Pacific partnerships

The US-initiated Partners in the Blue Pacific (PBP) — an informal group formed in June 2022 and aimed at boosting economic and diplomatic ties with Pacific Islands nations — directs assistance towards Pacific priorities such as climate resilience, sustainable ocean governance, and cyber security. Its members include significant development partners — Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States — who together accounted for about 77 per cent of regional aid in 2021. The group has the potential to pool finances and strengthen relationships without compromising bilateral engagements.

The partnership’s strength lies not only in its collective finances but in the members’ markets, technology, and educational institutions. For example, research has shown that, given the choice, Pacific people prefer scholarships from traditional donor institutions. [93] Higher education creates enduring and deep relations, often with future leaders. A collective initiative that provides scholarships to member countries’ tertiary institutions would have appeal, as would more access to science and knowledge networks. Similarly, joint programs to strengthen access to health, cyber, and digital expertise could build human and institutional bonds at a scale difficult for those with less convening power to match.

In the security realm, there are also opportunities for traditional partners to use their expertise and convening capacity to better integrate and support security agencies.

There remains regional scepticism about how the PBP will coordinate with regional and bilateral agencies, complement core policies such as the PIF’s 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, [94] and overcome unaligned member budgets, administrative systems, and priorities. Despite efforts to complement the PIF’s 2050 Strategy, [95] it still needs to demonstrate the capacity to deliver where it matters — in market access, climate action, people-to-people relations, and human development.

Beyond government and donor collectives such as the PBP, regionwide professional networks well integrated with traditional partner counterparts also hold potential for influence. Examples include the Pacific Islands News Association (PINA), regional business councils, the Pacific Islands Law Officers’ Network (PILON), and the Pacific Islands Emergency Management Alliance (PIEMA). These Pacific-based associations play a unique and significant role in enhancing capacity and social accountability, and rarely attract resources from non-traditional donors. [96] They can be stabilising forces to advance traditional partners’ desire for accountability, prosperity, and stability.

In the security realm, there are also opportunities for traditional partners to use their expertise and convening capacity to better integrate and support security agencies. The Pacific Islands Chiefs of Police (PICP) and the Pacific Transnational Crime Network (PTCN) share law enforcement information, build regional policing capacity, and support enforcement of national laws. The support of Australia and New Zealand has been vital. The Joint Heads of Pacific Security (JHOPS) provide a means for law enforcement, defence, customs, immigration, and other security agencies to evolve systems to strengthen regional security and counter transnational crime and cyber threats. [97] These associations play a powerful convening role and can promote good governance in times of intense political rivalry and resource constraints.

Conclusion

In our China relationship specifically, the Albanese government will … cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, manage our differences wisely …

— Senator Penny Wong, Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, 2023 [98]

Australia and the United States are destined to compete with China as they seek to advance their national interests in the Pacific Islands. They have all co-existed for decades, but the stakes are now higher and the intensity of the competition greater. PICs have been clear that they do not want geopolitical rivalries to limit development options. Pacific leaders are more assertive about setting the development and security agenda but can struggle to get traction with limited resources and capacity to affect the actions of global powers.

Australia, the United States, and other traditional donors can help square this circle with an increased emphasis on regionalism and multilateralism. MDBs and regional agencies can raise standards of engagement, expand resources, and simplify resource access. They are also able to pool resources and meet the increasing need for large-scale investments, especially in infrastructure and climate resilience. In addition, regional engagements support strategic dialogues and coordination across donors and recipients.

The essential steps for traditional partners must be the strengthening of “partnership muscle” and the evolution of better integrated development finance systems. Cooperation among likeminded partners can lift project quality and sustainability, provided it does not come with unnecessary administrative burdens.

Strengthening regional agencies and aligning well with Pacific Islands policy are key. Traditional donors have an advantage with regional agency engagement because of institutional membership, and professional and personal networks. Well supported regional agencies expand people-to-people and professional networks, and elevate impact and influence. They are a valuable complement to the dominant bilateral engagements.

There is the risk that strengthening standards for development engagements will open gaps for others, with less burdensome standards, to fill. It is a risk, but consistency and sustainability are valued in the region. Fast but poor-quality aid, or politically motivated aid, has costs. With more than 80 per cent of development assistance offered by traditional partners or multilateral agencies, there is huge scope to stimulate a coordinated “race to the top” and thus a more stable and prosperous region.

Bilateral arrangements will continue to dominate the Pacific Islands aid landscape and will remain open to politicisation. But regional and multilateral agencies provide a tool to improve development engagement and showcase the value of strengthened approaches to finance and development support. Pacific Islands leaders and institutions hold the keys to addressing their desire for greater cooperation. The Pacific mantra “friends to all” is in essence about the sovereign right to choose partners and set the terms of engagement. Ultimately, changing the regional dynamic requires Pacific Islands’ leadership, supported by development partners, to advance sustainability and sovereignty.