Over the past few weeks, Oppenheimer, the Hollywood biopic about physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “Father of the Atomic Bomb”, has earned more than US$425 million at the box office. Cinemas in one notable country, however, have not contributed a single dollar to this total.

Japan, the country that bore the wrath of Oppenheimer’s work, does not yet have the film playing in any of its theatres. Nor is a release date set for the country.

This week marks the 78th anniversary of the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Japan, the events are marked with solemn remembrances – whereas in the United States, they will go largely unnoticed.

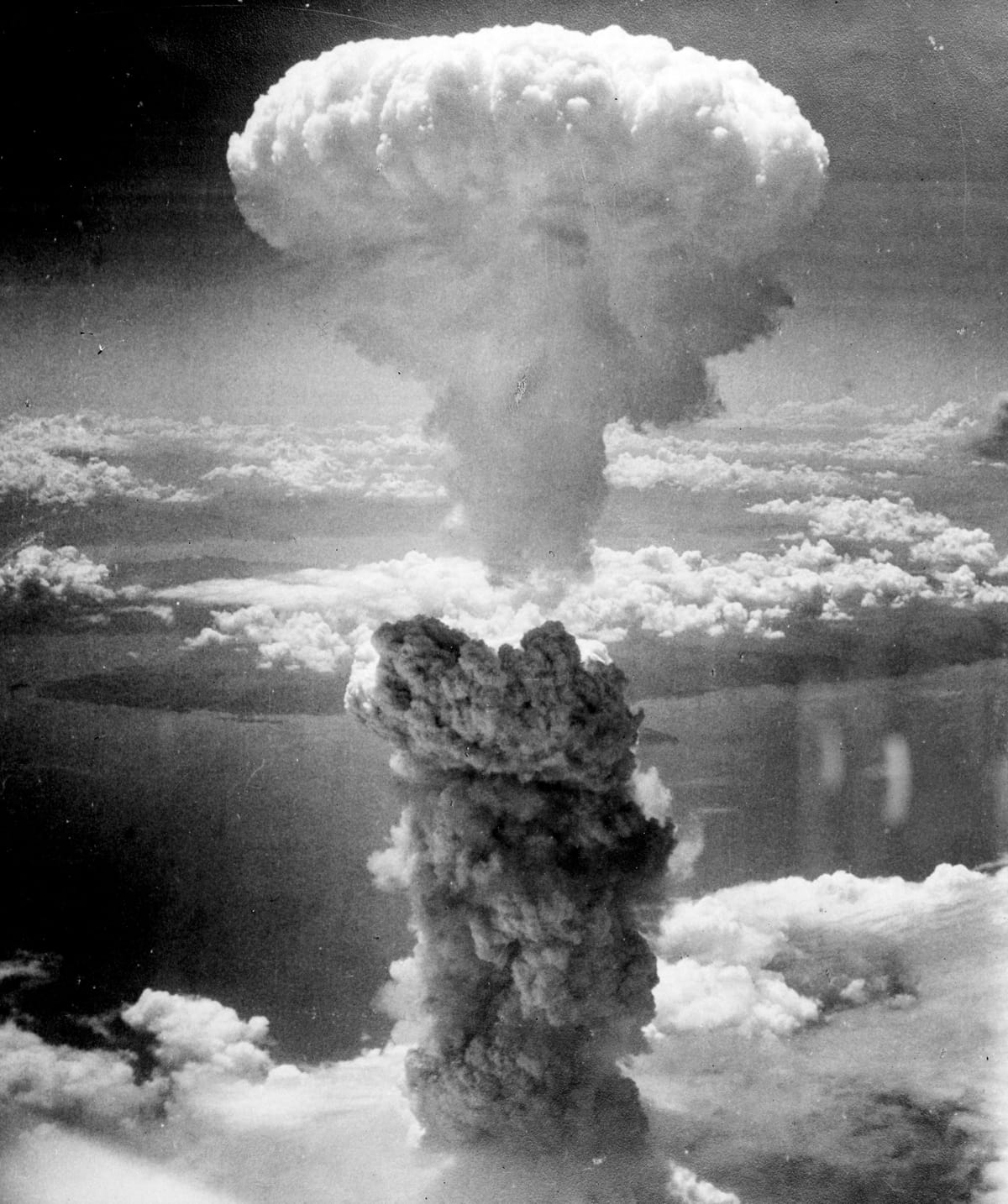

Although most Americans likely learned at school that the United States used nuclear weapons on these two cities at the conclusion of the Second World War, few will have ever seen more than black-and-white photographs of the damage that was wrought. Hardly any Americans will have spoken with a survivor of the bombings or understand how the effects of the bombs are still felt today. Instead, the bombing of the two cities is just another historical fact, something that was done to end a war against an aggressor who struck first. And as far as many Americans are concerned, that was the last time anyone died as a consequence of an atomic bomb.

The sensitivity about Oppenheimer in Japan serves as a reminder that when it comes to the history of America’s atomic bombs, the past is still very much the present. The proximity to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki anniversaries has caused Universal Studios to delay the film’s release. The bombings are not a subject to be taken lightly, and certainly not to be joked about. Warner Bros., which produced the new Barbie movie that has been frequently paired with Oppenheimer in social media memes, was publicly rebuked by its Japanese subsidiary and then issued a public apology when the movie’s official promotor appeared to support fan-created art that combined Barbie with atomic bomb-related imagery.

This was not the first instance of foreign entities getting caught in controversy related to the legacy of the bomb. In 2015, Disney Japan apologised for a tweet posted on the anniversary of the bombings which referenced a "birthday", and three years later South Korean K-pop band BTS had a show cancelled after a band member wore a t-shirt showing a photograph of the Nagasaki bombing next to slogans about Korean independence from Japanese rule.

Nuclear legacies are regularly controversial in Japanese politics. Most recently, heightened awareness and anxiety about the effects of radiation has engulfed the Japanese government as it prepares to release radioactive water from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

Such legacy questions are not confined to Japan. Approximately 4,500 kilometres to the south east lies the Republic of the Marshall Islands, an archipelagic nation made up of 29 atolls and five isolated islands. Between 1946 and 1958, the United States used two of the Marshall Islands, Bikini and Enewetak, to conduct 67 tests of atmospheric atomic and thermonuclear weapons.

The 1954 test of a hydrogen bomb caused dangerous levels of radioactive fallout on Rongelap and Utrik, two of the Marshall Islands’ populated atolls. And the cumulative effects of these tests continue to plague Marshall Islanders even today, as made clear in recent testimony by the Speaker of the Marshall Islands’ parliament to the US House of Representatives Natural Resources Committee. In addition to health ramifications, many of which are yet to materialise or be diagnosed, a concrete dome built to house more than 75,000 cubic metres of radioactive waste is now leaking into Enewetak’s already-radioactive lagoon.

The need to acknowledge the on-going effects of the US nuclear testing legacy is not only a moral imperative but is also important to America’s national security and geopolitical strategies. This was evident through the negotiations between the United States and Marshall Islands concerning the renewal of portions of the Compact of Free Association between the two countries. Access to Marshall Islands’ land and maritime territory is a critical component of the United States’ ability to keep shipping and communications links free and open, and to project military power into the western Pacific. Although these military access rights were not up for negotiation, America’s failure to adequately address its nuclear legacy could drive the Marshall Islands’ government and people towards other countries that are less friendly to the United States.

Unless the United States confronts the legacy questions of the bomb, it will be much harder to portray itself as a country committed to justice and respect the region.