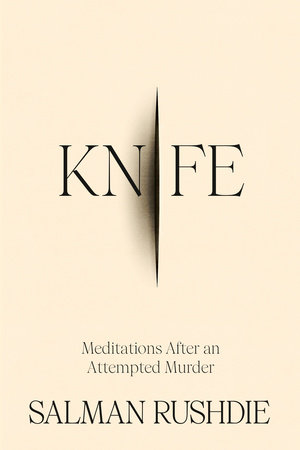

Review: "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder", by Salman Rushdie (Penguin, 2024)

Having already written an intriguing account of living under sentence of death (Joseph Anton), Salman Rushdie has now tried to make sense of the day when that death threat was nearly carried out.

Thirty three years before Rushdie was stabbed at a literary event in Pennsylvania, the government of Iran issued a fatwa, condemning the author to death for allegedly blasphemous passages in his novel, The Satanic Verses. That barbarous outbreak of “religious totalitarianism” (to borrow a Rushdie phrase) claimed victims, but not the author himself. (Nonetheless, there were six foiled attempts to murder Rushdie.)

Aged 75, after more than three decades and sixteen more books, Rushdie was attacked by “a murderous ghost from the past”. The would-be assassin had read no more than two pages of Rushdie’s works. Rushdie’s injuries were so grievous that each injured part of his body is accorded separate treatment, both medical and literary, in this book.

Although Rushdie will never be well again, as a writer he is back, with all his quips and quiddities intact. Despite its grim subject and gruesome detail, Knife is witty, often funny, boundlessly curious and richly allusive. The book might also serve as therapy, helping Rushdie achieve the “rehabilitation of mind and spirit” which he has sought since the stabbing. “The calamities of our yesterdays” are held at bay on each page. Sometimes even whimsy is allowed to intrude, as in Rushdie’s arguments about our possessing a mortal rather than an immortal soul, or his delight in the “everything-at-once-ness” of New York.

I have met Rushdie only once. We enjoyed an animated discussion about the personalities of an Iff and a Butt, then the kingdoms of Dup and Chup. For readers who have missed a true treat, those landscapes and figures populate Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories. I had praised that exceptional children’s book, prompting Rushdie to inquire with unfeigned glee about reading the story to my young son, whether Tom finished chapters and read on himself, and how a book could be passed from one generation to another.

That meeting occurred in the worst days of the fatwa. Rushdie entered the room hunched, his eyes flicking anxiously around. He was a man transformed when we started to talk about a world of words and a sea of stories. Rushdie was enraptured and enthralled by his craft; Knife demonstrates that he still is. For half an hour he seemed no longer hobbled and constricted by the fatwa, but master of his realm, the realm of a magician practising literary alchemy.

Rushdie has again become, unavoidably and almost fatally, the poster card for free speech. He notes dryly, “the first lesson of free expression – that you must take it for granted”. Knife is certainly not a polemic, nor even an extended defence of freedom, “that much-battered word”. Instead, Rushdie contends, quite insistently, that “love is a force”, one capable of confronting and overcoming hatred, fear, prejudice and ignorance. That is a noble and ennobling argument.