Emerging markets are under pressure from events in the global economy, including the normalisation of American monetary policy, the strengthening of the US dollar, and President Donald Trump’s trade war. Heightened risk perception is causing substantial outflows of foreign capital from the emerging economies. Australia’s region, however, seems to be coping without drama.

But the surges and retreats of foreign capital flows pose the question: how could they be made less volatile and thus more beneficial?

For decades, conventional wisdom has urged emerging economies to integrate their financial sectors more closely with advanced economies and adopt freely floating exchange rates. This was expected to provide additional funding, raising investment and growth. A freely floating exchange rate was supposed to remain stable, fostering steady capital flows.

When this worked out disastrously (for example, the 1998 Asian crisis), the standard assessment was that the fault lay with the recipient countries, which had not followed the prescription closely enough: “Should try harder”.

But the evidence is accumulating that short-term flows are intrinsically volatile, with surges and retreats reflecting changes of mood (“risk-on”, then “risk-off”) in the investing economies.

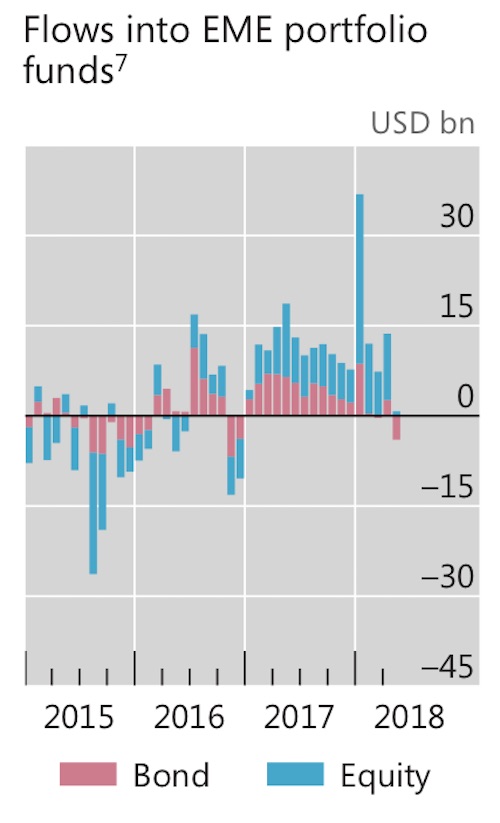

The latest Bank for International Settlements annual economic report provides details on one important component of the flow: foreign investment that comes via managed portfolio funds which buy emerging-economy bonds and equities on behalf of foreign savers.

It was a nervous year in 2015, with net outflows, especially in the second half of the year. By 2017 foreign portfolio investors had their mojo back, helped by the “push” factor of low returns at home and a weak US dollar. Now the flow has turned negative again.

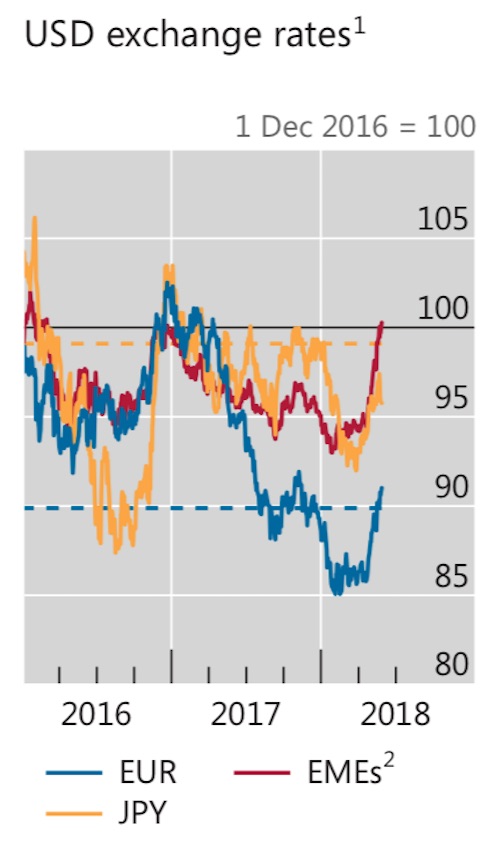

The recipient countries in our region have, for the main part, learned to live with these fluctuations. Their exchange rates are flexible (if not quite floating freely). The graph below shows that the exchange rates of emerging markets (red line, with a rise denoting a depreciation of the currency) didn’t fluctuate as much as the euro (blue) or the yen (yellow).

In our region, exchange rates have depreciated, but roughly in line with the global appreciation of the US dollar. The renminbi, rupee, and rupiah have fallen less than 10% over recent months – not much different from the weakening Australian dollar.

This may, however, conceal underlying stresses. These countries routinely use their substantial foreign exchange reserves to smooth their exchange rates. This is not costless: they are holding low-return foreign assets, waiting for the moment when these will be used to support the exchange rate for fear of overshoot.

Moreover, their macro policies are constrained by the threat of outflow. These countries have learned that they have to keep their budget and external deficits on a tight leash. Perhaps this discipline is useful, but it certainly diminishes the benefits of international capital flows in meeting the local savings shortfall: they can’t draw too deeply on this fickle source.

How can these flows be made more stable and thus more useful?

Conventional wisdom says that when these emerging economies are able to fund their deficits with local-currency-denominated bonds, the foreign flows will be more stable because the foreigners know that the debtor country can always pay back debt issued in its own currency. This, however, was always a misguided argument. Foreigners who have lent in local currency still have a compelling reason to flee in response to exchange rate concerns, as they don’t want to be paid back in depreciated currency.

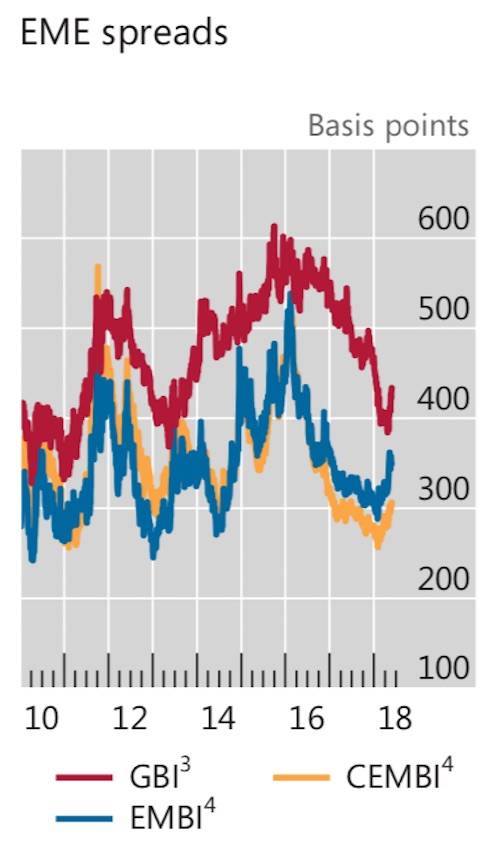

Thus, in practice, local-currency debt yields move more than dollar-denominated yields when risk-aversion rises. The red line in this graph shows how the yield margin on emerging-economy local-currency debt (the difference between yield on this debt and US dollar–denominated debt) widened during the outflow period 2015–16, compared with the margin on dollar-denominated debt (the yellow and blue lines).

What are the lessons?

First, developing domestic bond and equity markets will encourage local saving and intermediation, which is a good thing. But this doesn’t solve the problem of volatile capital flows.

Second, it makes sense to manage fragile exchange rates in emerging economies rather than allow a pure free-float. But that doesn’t mean over-managing. If the exchange rate and bond yields are allowed to move significantly when outflows occur, this would impose an appropriate penalty on fickle foreigners who routinely flee like lemmings whenever sentiment changes.

Other measures might discourage the fair-weather investors: transaction taxes, minimum holding periods, tight macro-prudential rules and effective imposition of income taxes.

None of this fits the conventional wisdom of encouraging seamless financial integration. But if such measures discourage some of the flighty foreign investors, so much the better. Better still if the foreign funds come in the form of foreign direct investment or stable company-to-company loans.