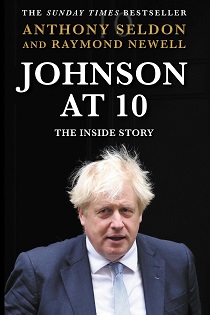

Book review: Johnson at 10: The Inside Story, by Anthony Seldon and Raymond Newell (Atlantic, 2023)

Are we better off waiting for tardy but considered analyses of our political leaders, magisterial books like Hugo Young’s dry and measured appraisal of Margaret Thatcher (One of Us) or Robert Caro’s interminable, grumpy biography of Lyndon Johnson (now onto its fifth volume)? Or is a quick-and-dirty, tick-tock account of political flaws and failures a superior guide to politics in the raw?

Johnson at 10 tries to have it both ways. Published only eight months after Boris Johnson’s resignation as UK Prime Minister (in July 2022), the book claims to tell “the inside story”, based on a couple of hundred conversations. Sources often remain anonymous, appearing merely as “an official” or “an aide”. The authors seem confident that their judgments, reached on the basis of recollections “where meetings of crucial witnesses are still fresh and moments remembered in context”, will stand after later release of memoirs, inquiry reports and official papers. Here as elsewhere, readers might recall Hunter Thompson’s warning that discussions that matter most usually occur behind locked doors at the end of guarded corridors.

Those seeking a more exuberant take on the Johnson years should turn to Marina Hyde’s delightfully scattershot, scathing sketches (now collected between covers as What Just Happened?!).

Seldon, in particular, has written about Britain’s leaders as often as Bob Woodward has about power brokers in Washington. He has now encountered a subject who continually disappoints him. In an era when we are intrigued by the cult of the strongman, Seldon’s and Newell’s is a dissection of an anti-strongman.

They portray a man demonstrating “an inability to value truth and to set or pronounce on moral boundaries”. They excoriate Johnson for “indecision, lack of detailed grasp, disorganisation and, above all, a tendency to avoid difficult decisions and conversations”. “Lacking moral compass, his judgments were made on faux loyalty and political expediency.” Imagine the invective that might be reserved for a much shorter Seldon–Newell treatment of Liz Truss’ miserable 44 days in office.

Some readers, let alone those still beguiled by Johnson, might find this analysis repetitive, insistent, occasionally arch. Where some might focus on Johnson’s intellect, charisma and charm, for instance, these authors mark him down as “the master of pandering to his flock”.

Seldon and Newell go into bat for Britain’s institutions and conventions against Johnson’s iconoclasm and perceived lack of seriousness. They emphasise the importance of learning how to make Cabinet productive, how to be seen to defer to parliament, how to prod or nudge Whitehall’s machinery of government.

Representatives of those institutions have seen off Johnson’s (and Dominic Cummings’) iconoclasm, blue sky thinking, big picture illusions and “levelling up”. Perhaps “optimism and comedy are no substitute for what all Prime Ministers need: dignity and gravitas”. Britain’s institutions, though, need to respond robustly, modernising (in infrastructure especially) and renovating (the national health service) if the old paradigm of “dignity and gravitas” is to have any future.