Australian spooks are not a literary lot. The secret services of Britain and the United States have spawned many spy fiction authors, but we are still waiting for a domestic John le Carré (ex-MI6) or Charles McCarry (ex-CIA).

Nor do we have an Australian Mick Herron, a spy fiction author with no background in intelligence (as far as we know). While every second friend these days seems to be writing a crime novel, the “second oldest profession” is ignored for inspiration.

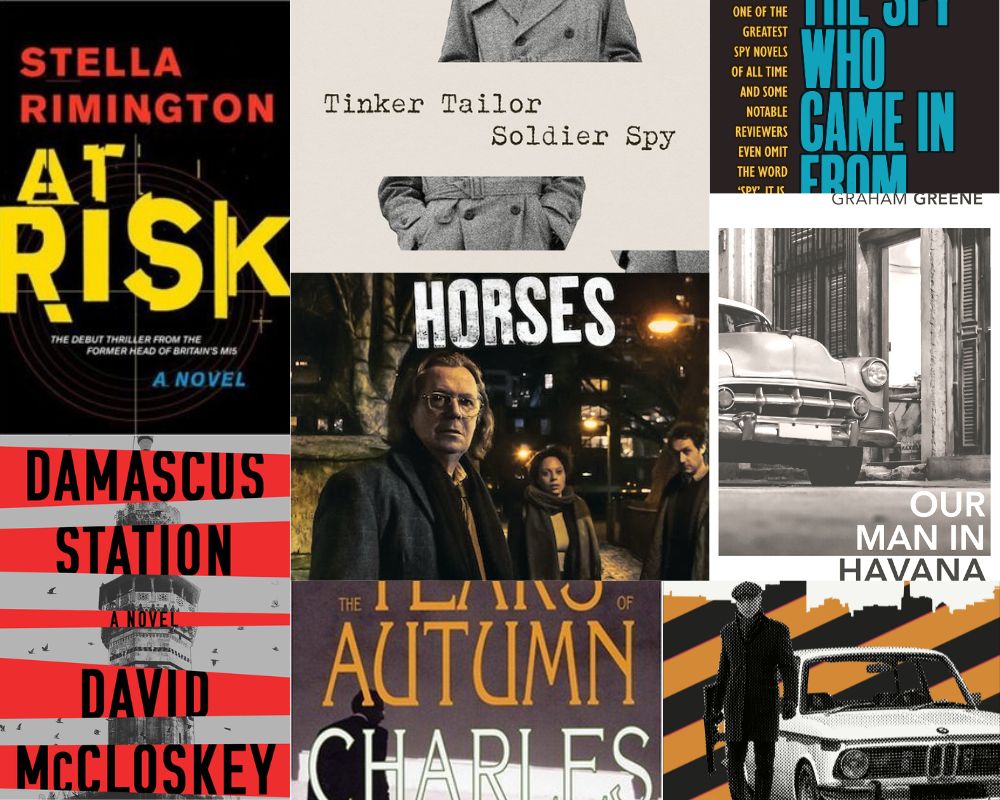

You also won’t find many women in the ranks of espionage writers, although Stella Rimington, a former head of MI5, is a welcome addition. Unlike crime fiction, where women readers outnumber males and female authors more than hold their own, women are supposedly not fans of the espionage genre.

Spy novels are also different from thrillers involving spies. The distinction is not clear-cut but is best drawn by contrasting le Carré’s George Smiley with Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne. There are no superheroes, and often no heroes, in spy novels.

The Economist recently featured a list of eight top spy novels, noting espionage fiction in the English-speaking world traces its origins to 1901, with Rudyard Kipling’s Kim. But it was not until the Cold War, and the founding of the CIA, that the genre took off. So my “top ten” list skips over authors such as John Buchan and Eric Ambler (to whom le Carré paid tribute for bringing realism to spy novels.)

First on my very Anglo-centric list is Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, which was le Carré’s seventh novel and has been made into a television series (1979) and a film (2011). Other le Carré books deserve to be on the list but I have reluctantly limited myself, with his fourth book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, as my number two.

Both novels involve the search for double agents, or “moles”, and this is a constant theme of spy fiction. Such plots remain realistic because of the real-life examples of “the Cambridge Five” in the United Kingdom, Aldrich Ames in the United States, and Oleg Gordievsky in the USSR.

Number three is Mick Herron’s Slow Horses, not because it is necessarily the best of his Slough House novels but because it is the first in a delightful series that should be read in order. Don’t think because you are now enjoying the superb television series (on Apple TV) you don’t need to read the books. If you do, you are missing out on a master writer and plotter as well as some of the funniest, laugh-out-loud dialogue.

American authors may have been late to spy fiction but, once the United States threw off isolationism, they took to it with enthusiasm. My number four is Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn, which pursues the JFK assassination in, of all places, Vietnam. McCarry is a former CIA field agent and must have his manuscripts vetted by the agency.

Number five is The Company by another American, Robert Littell, far and away the best novel of the CIA, spanning many decades. Littell’s output is as extensive as le Carré’s and he is often described as “the American le Carré”, which is unfair to both. Many of Littell’s other books deserve to be in the top ten, as do McCarry’s.

Number six is Len Deighton’s Berlin Game (the first book of a trilogy including Mexico Set and London Match), which have been republished. Deighton later published two more trilogies, all involving Bernard Samson, who shares many of George Smiley’s modest characteristics. Deighton is best known for The Ipcress File and Funeral in Berlin but his initial trilogy are my favourites. He insists each book stands alone but you will miss something if you read them out of order.

To show I am not obsessed by the Cold War, my number seven is Agents of Influence by David Ignatius, well known as a commentator on foreign affairs and intelligence matters. This novel, his first, is a thinly disguised account of a story he broke for The Washington Post: the CIA enlisted the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s head of security as a double agent until he was assassinated by Mossad.

No list can be complete without Graham Greene. He cannot be categorised as an espionage writer but it is a topic to which he kept returning, perhaps reflecting his own background in intelligence. Take your pick from The Human Factor, Our Man in Havana or The Quiet American. The latter is my number eight.

At number nine is Damascus Station by David McCloskey and, finally, An Honorable Man by Paul Vidich. Both are “new generation” espionage writers, relatively new for me and I am enjoying working my way through their catalogues. I reserve the right to substitute another of their titles in any future list but I suspect both authors will remain in my top ten.