Two months into the Trump Administration, is it overturning the ‘liberal world order’, as widely feared? By now we ought to have some idea. My conclusion: no, it isn’t. If there was a liberal world order in the global economy on 20 January, 2017, it is still there today. The Administration has startled the world with its eccentricities, but it is very far from changing anything much in the global economy, or even in the customary lines of major US foreign economic policy.

Take trade – the economic issue on which the new Administration most wants to make a big difference.

There has so far been no 40% tariff on imports from China or Mexico, or any serious suggestion of one. China was not declared to be a ‘currency manipulator’ from day one, as promised.

The new administration will indeed renegotiate the NAFTA trade agreement between the United States, Canada and Mexico, the deal Mr Trump described as the worst in history

But from overturning the world trading system, the NAFTA discussion is beginning to look like a routine trade negotiation.

Renegotiation itself is nothing extraordinary - President Obama, after all, promised during the 2008 campaign to renegotiate NAFTA, but didn’t get around to it. Most trade agreements have provisions permitting them to be revisited.

The NAFTA renegotiation won’t begin for at least another three months, and according to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross will take at least a year – if not more. Mr Ross says mildly that NAFTA ‘needs an update’ and the negotiation may produce ‘marginal benefits’ for the United States – a modest and probably accurate assessment. After discussion with the Administration this month, Mexico’s foreign minister told reporters there had been ‘no talk of unilateral action’.

Congress fights back

White House Trade Council director, Peter Navarro, a warrior for the unilateral imposition of US trade interests, had earlier suggested all trade deals be automatically renegotiated if the US trade deficit with the partner country increased. Congressional opinion was aghast. The proposal seems to have died, unlamented.

Navarro does not seem to be influential in either the administration or Congress. Earlier this month the Financial Times reported a stormy meeting in which Navarro’s views were contested by the Director of the National Economic Council, Gary Cohn, and disregarded.

China trade is the chief object of Trump’s wrath, but here the way forward is less clear. There is no bilateral trade agreement to renegotiate. The administration’s nominee for US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, who may be confirmed this week, was a deputy USTR in the Reagan Administration, where he was associated with the imposition of ‘voluntary restraints’ on steel and other exports to the US from Japan, Taiwan, Korea and Britain. He may well look to the same strategy this time around, though now it is more complicated.

The US joined the WTO on its creation as part of the 1994 Uruguay Round conclusion. The WTO has a clearer and more comprehensive trade dispute resolution process to which China can, if it wishes, refer US threats of trade sanctions.

Navarro was highly likely the author of the Trade Policy Agenda document issued by the USTR office in early March, with its insistence that WTO dispute rulings are ‘not binding’ on the United States. Reports suggested key members of the trade-related committees of the House and the Senate were unhappy with this stance.

It will be quite plain to congressional leaders that if WTO dispute findings against it are disregarded by the US, findings in its favour are likely be similarly disregarded by its trading partners. Since the US launches far more disputes than any other WTO member, disregarding the rulings is not on the face of it a good idea.

The WTO lists 114 disputes in which the US is or was the complainant – far more than any other WTO member. There are 97 cases in which the EU is listed as complainant, 23 for Japan and only 15 for China.

Nor are the congressional trade leaders happy with the prospect of extensive unilateral sanctions, wisely judging the target countries will respond. Secretary Ross has in any case made it plain that anti-dumping cases, the main vehicle for US punitive sanctions against trade partners, remain within the authority of his department, not elsewhere.

The key official in trade policy will not be Navarro but Lighthizer. A trade lawyer for decades, one who has worked for foreign as well as American firms, he will have plenty on his plate without picking fights that will not be supported in congress, and risk US export opportunities.

Within the Administration there are no doubt experts pointing out that these days there are not many jobs in the US to protect against Chinese imports. They are no longer there in textiles, clothing and footwear, or in the cheaper end of household appliances and tools. Where there is competition in manufacturing output it will increasingly be between robots, not people.

Chrysler Group assembly plant in Michigan (Flickr/Fiat Chrysler Automobiles)

It would not harm the global economic order if the US aggressively pursues a new intellectual property deal with China, whether as part of the WTO or bilaterally. The new administration will highly likely pick up the negotiation of an investment agreement with China at the point the Obama administration left it, again with no injury to global trade or investment.

Meanwhile, the business of managing America is taking over from the campaign speeches. US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is to soon visit China, while President Xi is now scheduled to visit Mr Trump in April. Reality intrudes.

The immediate US trade agenda is now said to be the renegotiation of NAFTA, and a bilateral trade deal with Japan. Neither pose any threat to the world trade system, or the global order. It is not impossible Lighthizer will continue negotiating the Obama Administration's Trans Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with Europe. It is after all a bilateral. If the US wants to negotiate a trade deal with members of the European Union, including (and especially) Germany, there is no other way to do it.

Trump can't destroy what's not there

What, anyway, is this global order that the Trump administration is said to challenge? Among global security analysts it is the post-World War Two Pax Americana, now said to be collapsing. Perhaps so, but from an economists’ perspective the post-war liberal economic order vanished a long time ago.

The US remains far and away the most formidable military power on earth but if it was ever an economic hegemon it ceased to be so with the recovery of Western Europe and Japan half a century ago. Today the US accounts for around one fifth of global economic output. Depending on how measured, its output is a little less than China’s.

If there was a global economic order in recent economic history, it was the post war system of fixed exchange rates monitored by a powerful IMF. That too vanished half a century ago.

Global trade negotiations have likewise disappeared. There hasn’t been one of those successfully concluded since the Uruguay Round agreement in 1994. Bilateral trade deals, the favoured policy form for the Trump administration, are now far more usual than global or multilateral deals. Australia, for example, a medium-sized trading nation, has nine bilaterals and just one plurilateral trade agreement, not counting its WTO membership.

The same is true more broadly of world economic coordination. These days, there isn’t any. From its heyday in the 1980s the G7 group of major advanced economies has faded away as a serious forum for ordering the global economy. Who would now pay attention to a global group that included Britain and Canada, but excluded China (let alone Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Saudi Arabia and maybe Australia)? Meeting Friday, G20 Finance Ministers will usefully swap notes on the Trump administration and the global economy. Coordinate the global economy they will not.

And while it was confidently expected a couple of decades ago that liberal market democracy would become the pattern for all significant nations, it hasn’t happened. In one form or another, democracy has had some good wins, but the forms of market economies have proved to be remarkably various.

The main elements of the liberal world order in an economic sense are an openness to trade, technology and capital flows. Of the three, only trade - and, of that, mostly only trade in goods - subject to agreed international rules. But those pillars don’t appear to be under stress, even from the Trump Administration.

World trade picking up

After a sharp decline over the last eight years the growth rate of cross border trade is picking up. That, at least, is the signal given by the most recent WTO world trade indicator and by the World Trade Monitor of the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis.

Examining the decline in trade growth, an October 2016 report from the IMF attributed the slowdown ‘very largely’ to a decline in industrial production growth, a decline in investment, and a decline in cross-border production chains as economies like China’s moved beyond assembly. The impact of what the IMF thought to be a ‘recent uptick in protectionist measures’ had been ‘relatively limited’.

It’s certainly true that capital flows are well down compared to the levels before the 2008 crisis, though they are rising again. But much of this is a welcome response to a keener sense of risk arising from that crisis, and from constraints imposed on financial institutions leverage as a result of that crisis.

As a share of GDP, foreign direct investment is much the same as before the 2008 crisis, and well up on where it was a couple of decades ago. Twenty years ago global direct cross border investment flows were 1.2% of global GDP. In 2015, the latest year for the World Bank data, direct cross border investment flows were more than double, compared to GDP.

The US economy is doing quite well

During the election campaign Trump falsely portrayed both the US and global economy. In office, the Trump administration has to deal with the world as it really is. Far from collapsing, for example, the US economy is actually doing quite well – well enough for the US Federal Reserve to cease additional bond purchases several years ago, and to have increased the policy interest rate. Unemployment in the US is low, jobs growth is firm, wages are rising.

While manufacturing employment in the US has tumbled, a source of discontent and rebellion in industrial states that swung into the Trump column, American manufacturing is doing pretty well.

US manufacturing output by volume is up by nearly a third compared to the year 2000, when China was admitted to the WTO. And though manufacturing over the period has fallen as a share of GDP from 14% to 12%, manufacturing has also fallen as a share of China’s GDP, and by the same percentage. In neither case has manufacturing as a share of GDP fallen by as much as it has in the global economy as a whole. Services are an increasing share of GDP, and not just in the United States but in China and in the global economy as a whole.

So, too, global output growth is firming. China is sustaining growth above 6%, Europe is continuing to expand despite its political tangles, and Japan has avoided another recession. Brazil and Russia, two economies that encountered sharp downturns, are picking up.

Nor is the pattern of global growth quite as unwelcome to the US as it was a decade ago, when Ben Bernanke complained of a global savings glut driving up the US current account deficit and the Chinese current account surplus.

Both the American deficit and the Chinese surplus have sharply contracted. In 2007 China’s surplus peaked at 10% of GDP and by 2015 it had fallen to less than a third of that share. The US deficit peaked at nearly 6% of GDP in 2006 and by 2015 was just over half that share.

Driving the changes have been an improvement in the US trade deficit, and a deterioration in China’s trade surplus. US exports have increased sharply as a share of GDP while China’s exports have fallen – and much more sharply. A decade ago US exports were 11% of its GDP. Last year they reached 13% of GDP, a little down on the record high of 14% of GDP in 2014. By contrast exports were 37% of China GDP a decade ago, and had fallen to 22% in 2015.

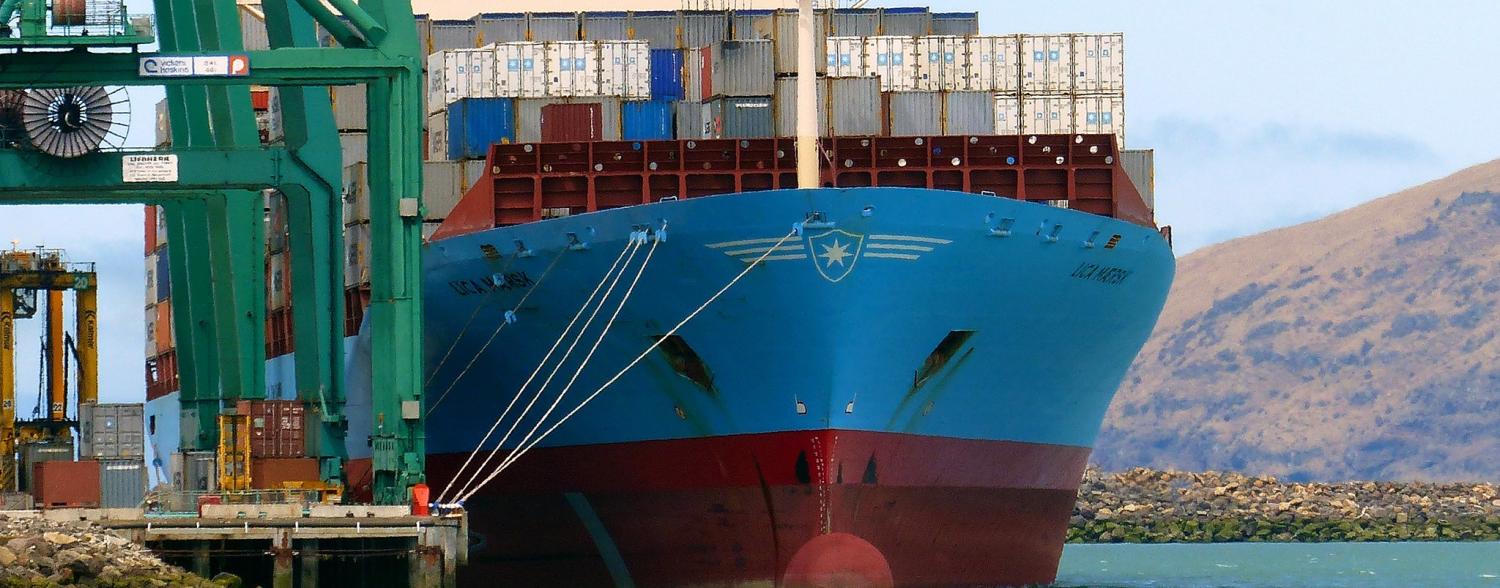

Shipping containers, Morgan's Pt, Texas (Flickr/Blake.Thornberry)

Gloomy prognostications about the impact of the Trump administration on global economic rules link in to a narrative about the decline of the American role in global security. But while the realms of economics and global security are related, they follow different rules. In her 1992 book Systems of Survival Jane Jacobs illuminated the distinction between the guardians of societies, and commerce. Both are necessary, but they are always in tension and have been through the thousands of years of trade between communities. The guardians worry about security and suspect their neighbours. The commerce people look to their neighbours for deals. The difference is one reason why the analogy between the realms of global security and the global economy founders.

Whatever may be happening to the global security system, the global economy is growing, prospering, and is every day more closely integrated – notwithstanding the Trump Administration. In his most recent book The Great Convergence, trade economist Richard Baldwin makes the point that with artificial intelligence, automation, improving visual communications and so forth globalisation is getting a second wind. As usual, government policy (including US policy) runs well behind developments in the global economy. It isn’t orderly, but it works.