The Australian government has officially blocked Chinese telecommunications firms, most notably Huawei, from providing equipment to Australia’s new 5G mobile phone networks, citing concerns over national security.

While the issue in question regards some of the world’s most sophisticated communications technology, at its core, it deals with human interaction at its most primitive. When it comes to Huawei and Australia, it all comes down to trust – or lack thereof.

While refraining from mentioning the company by name, Scott Morrison – acting as Home Affairs Minister during the government’s leadership turmoil – said in a statement on Thursday that it would bar any firm “likely to be subject to extrajudicial directions from a foreign government that conflict with Australian law”. This seems to be a reference to China’s National Intelligence Law, enacted last year, as well as the country’s authoritarian political system, which lacks an independent judiciary.

The intelligence law has been met with some consternation from foreign governments and analysts, as it compels “all organisations and citizens” to assist in the country’s intelligence work. It should also be noted, however, that it remains unclear as to if or how, exactly, this has changed how Chinese intelligence agencies work with the country’s telecoms providers overseas.

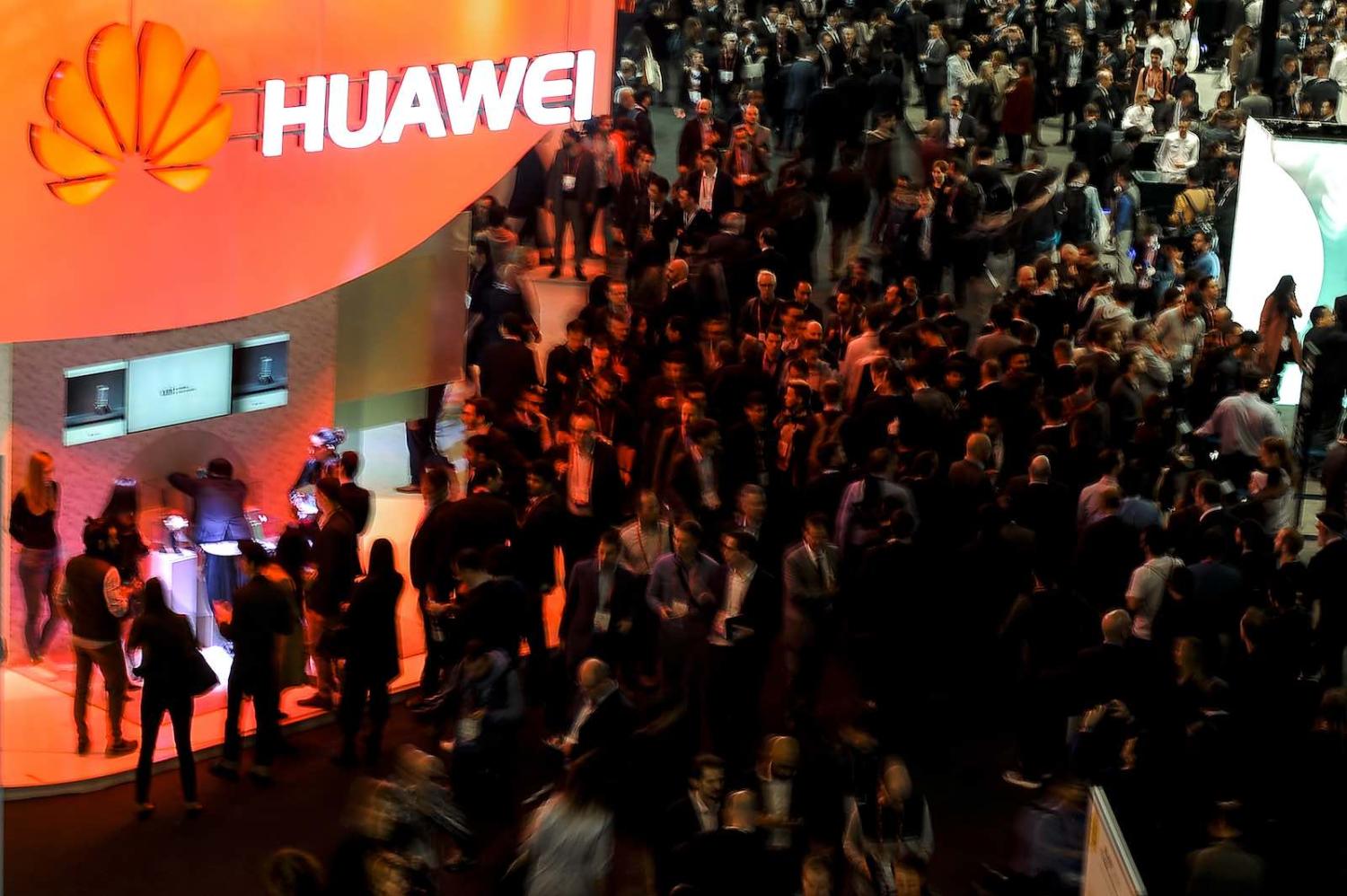

The ban delivers another heavy blow to Huawei in 2018, which has seen their hopes for expansion into the US dashed, and their UK business threatened. In a Twitter post responding to the news, Huawei Australia said that it was a “disappointing result for consumers”, and emphasised their 15-year history of operating within the Australian market.

We have been informed by the Govt that Huawei & ZTE have been banned from providing 5G technology to Australia. This is a extremely disappointing result for consumers. Huawei is a world leader in 5G. Has safely & securely delivered wireless technology in Aust for close to 15 yrs

— Huawei Australia (@HuaweiOZ) August 22, 2018

Huawei has a trust problem

Australian officials are far from the only group with whom Huawei suffers from a deficit of trust. When speaking with current and former Huawei employees for research into an article on the firm’s corporate culture published last year, complaints over their environment of mistrust were exceedingly common, both from foreign and Chinese employees alike.

This seems to be partially by design, as Huawei is known for using intense internal competition, known as “horse races” (赛马) to keep employees on-edge and motivated. While this has helped Huawei establish its reputation for low-cost, high-speed results, the side effect of such an approach, say those close to the company, is hindered collaboration and poor internal communication.

Insularity and secrecy may be a major contributor to Huawei’s struggle in building a likeable and trustworthy global brand image.

This, among other factors, has led to an environment of secrecy, which has led to an array of blunders in its government and public relations. This includes a 2010 incident in which Indian security officials probed the company’s Bangalore office after learning that entire floors of the building were deemed off-limits to local staff, with only Chinese managers having been given clearance to enter, and accusations of “paranoia” when PR staffer told a group of journalists on a government-organised tour in Shanghai that they could not mention the Chinese electronics company in their reporting from the day, after the question of national security was raised.

Despite being the world’s largest telecoms company, Huawei remains privately-held. Their founder, Ren Zhengfei, is a former military officer, and the firm’s relationship with the Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army remains an issue of concern and opacity. They are also incredibly insular, as of the company’s 17-person executive team, none has been with the company for less than 20 years.

It is its insularity and secrecy that may be a major contributor to its struggle in building a likeable and trustworthy global brand image, despite investing heavily in marketing and PR campaigns, often with the world’s most recognisable agencies.

It’s hard to find an appropriate way to phrase this, but Huawei’s executives just seem to have trouble showing that they empathise with their overseas markets, or that they recognise and respect the values which those cultures hold dear. Huawei’s struggles in Australia come as the country is redefining its relationship with Chinese companies, as many in the country are concerned about the influence operations of the Chinese Communist Party. What seems needed is reassurance from companies such as Huawei that they respect Australian sovereignty and privacy, as well as their core values like freedom of speech and human rights.

With fear among the Australian public on the rise, and their business there in jeopardy, Huawei placed a series of full-page advertisements in the country’s major newspapers in an attempt to build goodwill with the public. The message: One in every two Australians depend on Huawei for their communications needs.

Today Huawei has full page ads to highlight its global ICT leadership. Huawei already partners with 45 of the world's top 50 telecom operators. #Ausbus #Auspol pic.twitter.com/fZ9zhMc6I4

— Huawei Australia (@HuaweiOZ) July 12, 2018

In other words, with the people of Australia questioning whether they should rely a potentially untrustworthy provider for their telecommunications needs, Huawei responded with “you already do”. In other words, in an attempt to calm a fearful public, Huawei used the horror movie trope of “the call is coming from inside the house”.

While it is unlikely that a PR campaign would have swayed the opinion of the Home Affairs Ministry anyway, one can imagine that these adverts may have had the opposite of their intended effect.

The trust issue is bigger than Huawei

Looking at Huawei’s struggles to build goodwill in overseas markets, there is much that seems to be out of their control. As stipulated in China’s National Intelligence Law, companies must assist in its government’s intelligence work if asked, and even if such a law were not on the books, refusing to comply with such requests is not generally considered to be an option.

Under the direction of the Chinese Communist Party, Chinese hackers have conducted a series of cyber attacks on Australia and its allies, including the US federal government’s Office of Personnel Management, and major Australian research institutions, including Australian National University. With regards to core Australian and Western values, internal CCP documents emphasise the need for the party to continue in an “intense ideological struggle” against such concepts as “universal values”, “Western constitutional democracy”, “civil society,” and “the West’s idea of journalism”.

It is entirely possibly that the Chinese Communist Party is misunderstood. However, it does seem that at this time of heightened international tension, they are struggling to reassure much of the world of their benign intentions. So far, Chinese companies like Huawei seem to be paying the price.