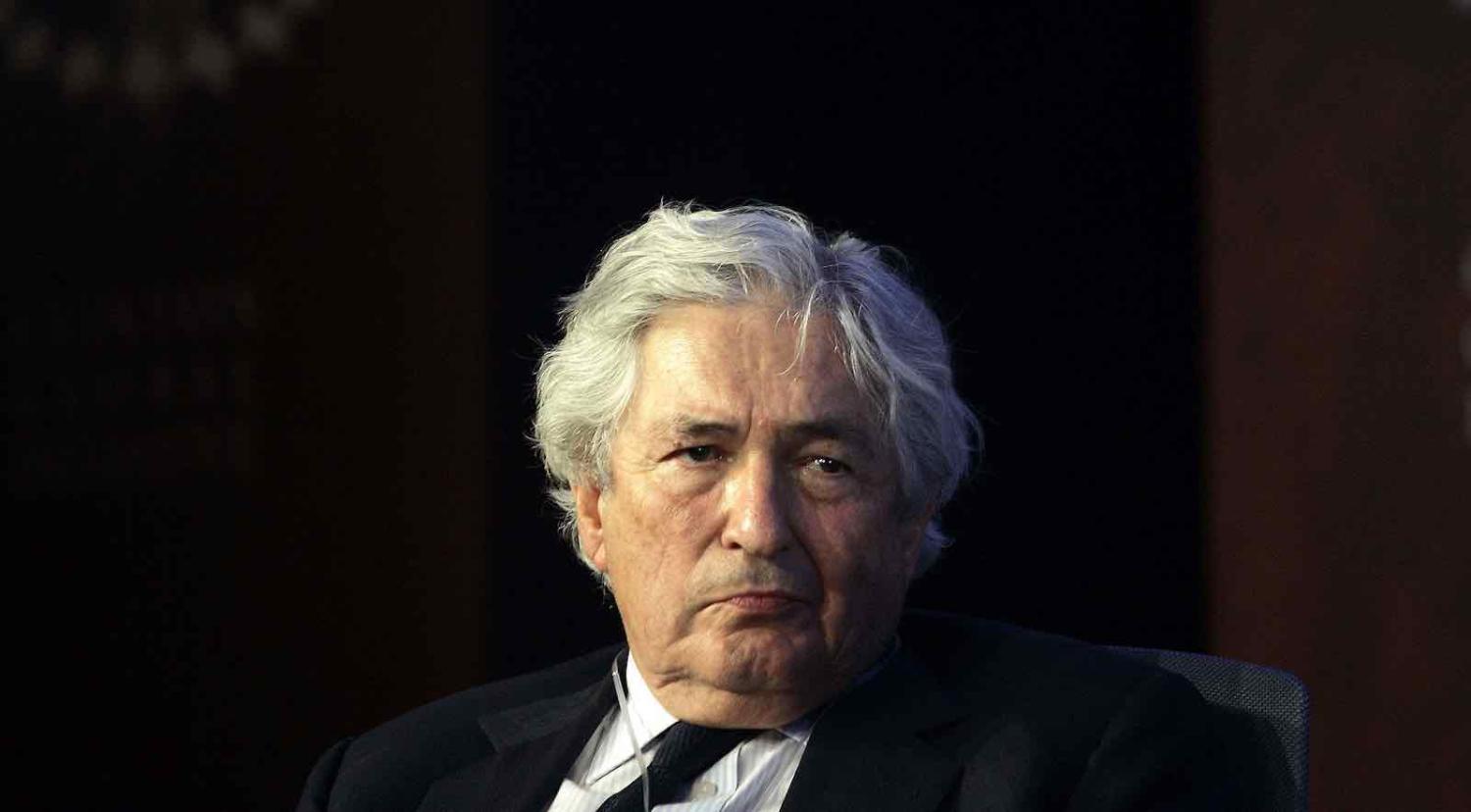

Jim Wolfensohn, an Australian-turned-American who became president of the World Bank in 1995, was a mercurial character. His struggle to tackle the challenges of global development, relying on the weak reed of the World Bank, is a classic story of the heroic individual challenging global forces. Global forces won, but it was a dazzling struggle.

Wolfensohn died in his home in Manhattan last week. In many ways, Wolfensohn’s knowledge initiative that he championed at the World Bank changed the global debate about development policy.

Born in 1933 in Sydney, Wolfensohn grew up in Australia. After studies in both Australia and the United States, he moved to the US in the late 1970s. He worked successfully in finance and investment, cultivating elite contacts in Washington and New York. Even at this stage – though he was still only in his mid-40s – he had set his eye on the presidency of the World Bank. In 1980, the outgoing president of the Bank, the legendary Robert McNamara, encouraged Wolfensohn to think that he was perhaps in the running for the job.

In an effort to bolster his chances, Wolfensohn took US citizenship. But the gambit didn’t work. Not immediately. US President Jimmy Carter appointed a nondescript New York banker, Alden Clausen, to the job. In the event, Wolfensohn needed to wait another 15 years and watch three mediocre presidents hold office before he was selected.

In those 15 years, Wolfensohn built up his own successful investment firm in New York. He had a dazzling list of high-flying international contacts in America and Europe. Anybody who was anybody was on Wolfensohn’s “golden Rolodex”. He became the chair of Carnegie Hall, and later chair of the John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts in Washington. He took lessons from famed British cellist Jaqueline du Pré before she died in 1987. In countless articles, Wolfensohn was described as a “Renaissance man”.

The breakthrough came in 1995 when Bill Clinton decided to nominate him for the top job at the World Bank. The presidency of the World Bank is in the gift of the US president, so Wolfensohn was soon confirmed in the job.

But the challenges for somebody like Wolfensohn in taking over the leadership of a sprawling international agency such as the World Bank were daunting, to say the least. The culture clash for Wolfensohn was confronting. He was used to the free-wheeling ways – and the personal freedom – of working in a small boutique financial firm in New York. Suddenly, he found himself in charge of a huge and lumbering bureaucracy, an international state-owned enterprise, subject to the whims and pressures of the governments over 180 countries who were the owners of the organisation.

Wolfensohn could afford to ignore the views of many of the countries much of the time. However, the larger and more influential countries – such as the United States, the main European nations, China, Japan, India, Mexico, plus a few other key nations – would often make their demands clear. Wolfensohn found both the sluggish internal processes of the World Bank and the incessant pressures from member countries very annoying. In The World’s Banker, an entertaining biography of Wolfensohn, journalist Sebastian Mallaby noted that “Wolfensohn is the most ambitious man I know”, but that his “chief failing was impatience”.

Wolfensohn responded to these frustrations with varying combinations of guile, charm, tantrums and deals. In the opening paragraph of The World’s Banker, Mallaby talks of “the two main characters” that he saw in Wolfensohn.

On one side there is Jim Wolfensohn – screamer, schemer, seducer; Olympian, musician, multimillionaire; by no means a saint … On the other side, there is “development”, an umbrella term for humanity’s most intractable headaches – ignorance, illiteracy, malnutrition, AIDS – the toughest challenges of globalisation … Jim Wolfensohn has grappled with all of these challenges.

Wolfensohn was a major force for change in the World Bank during the 10 years that he was president. To many in the Bank, he was wonderful. To others, his endless ideas for change created nothing but difficulties. Wolfensohn’s own views are set out in a valuable autobiography, A Global Life: My Journey Among Rich and Poor, from Sydney to the World Bank, which he wrote after he left the institution.

The idea that knowledge was important took the World Bank, along with the international development community, by storm.

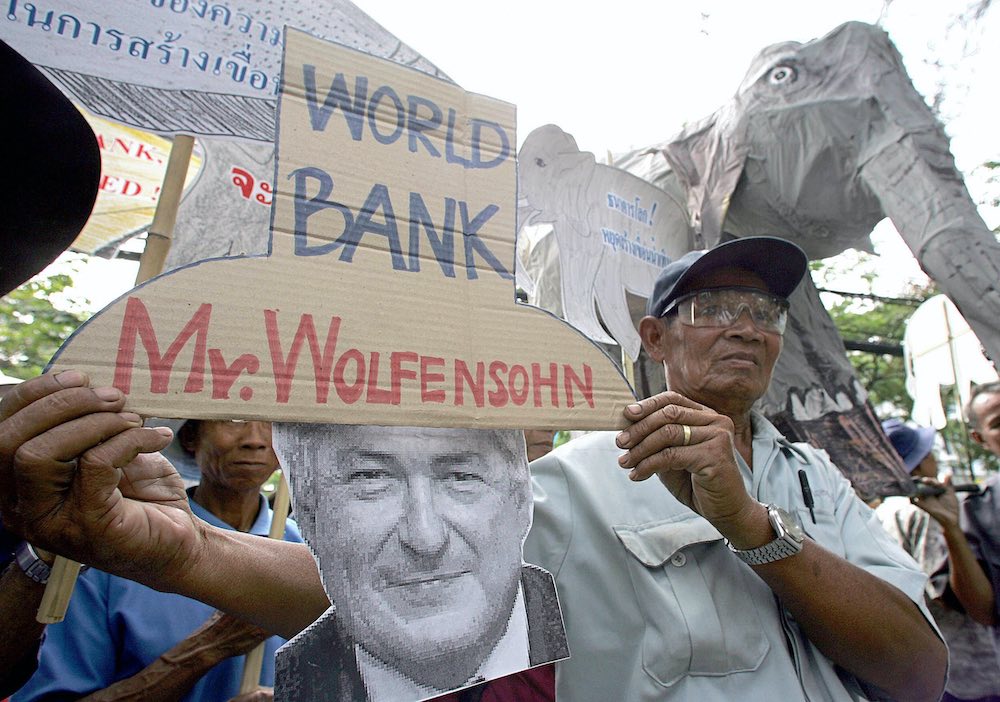

Looking back, it seems clear that Wolfensohn’s biggest challenges were in the first few years of his presidency. He arrived at the Bank in 1995 at a very difficult time. Protesters had disrupted the annual meeting in 1994, arguing that the Bank should be abolished. The institution had been established in 1945, so critics mounted a major campaign around the theme of “Fifty Years is Enough” which listed a multitude of alleged shortcomings in the organisation.

Wolfensohn was adroit in responding to the campaign. He quickly announced important internal reforms which, as a first step, blunted the force of some of the criticisms. He then, as a second step, signalled a major change in the culture of the institution by announcing that the Bank would actively attack corruption in developing countries.

Previously, the international community had been inclined to tiptoe around the problem of corruption in developing countries. Wolfensohn confronted the consensus. In his presidential address to the annual meeting of the Bank in Washington in 1996, before all of the ministers and delegates from member countries, he denounced the “cancer of corruption”. The result was twofold: a kind of intellectual dam was broken, and it quickly became more acceptable to discuss the problem of corruption in global development programs. And the World Bank suddenly appeared to be transformed and began to be seen as leading an international crusade against bad governance in developing countries.

But the problem that quickly arose was that the World Bank could not do much about the issue of corruption. Mallaby observed that:

By speaking out … Wolfensohn had scored a brilliant rhetorical coup, but what was the World Bank supposed to do about it? Wolfensohn did not have an answer to that question.

A third major Wolfensohn initiative – also announced in his 1996 annual meeting speech – was that the World Bank would become a “knowledge bank”. The idea was that the Bank should move away from old-fashioned projects such as roads and power stations and focus on knowledge. The Bank would pool its expertise in numerous subjects, from civil service reform to electricity generation in central databases. The knowledge would then be shared with developing countries.

The idea that knowledge was important took the World Bank, along with the international development community, by storm. The idea that there was knowledge in rich countries which could be shared to break through the barriers to global development was highly appealing. Development professionals and NGO activists alike in North America and Europe welcomed the idea. It pointed to a new and progressive role for the World Bank.

Before long, a focus on “knowledge” became the buzzword across the international development community. The fashion has lasted until today, not least because it is a convenient way for agencies in rich countries to be seen to be providing assistance to developing countries in a low-cost way.

Ultimately, the global problem of development that Wolfensohn was grappling with is a hugely complex kaleidoscope of issues. His goals were far too ambitious. Mallaby summed it up: “The World Bank is not a proxy for world government. Instead, it is a small institution relative to the problems it faces.”

Wolfensohn’s big contribution was to see those problems in a fresh light.