Myanmar’s former military regime often used new issues of the country’s postage stamps to send political signals, not only to its own people but also to the international community. It appears that this practice is also being followed by Aung San Suu Kyi’s quasi-democratic government, which took office in 2016.

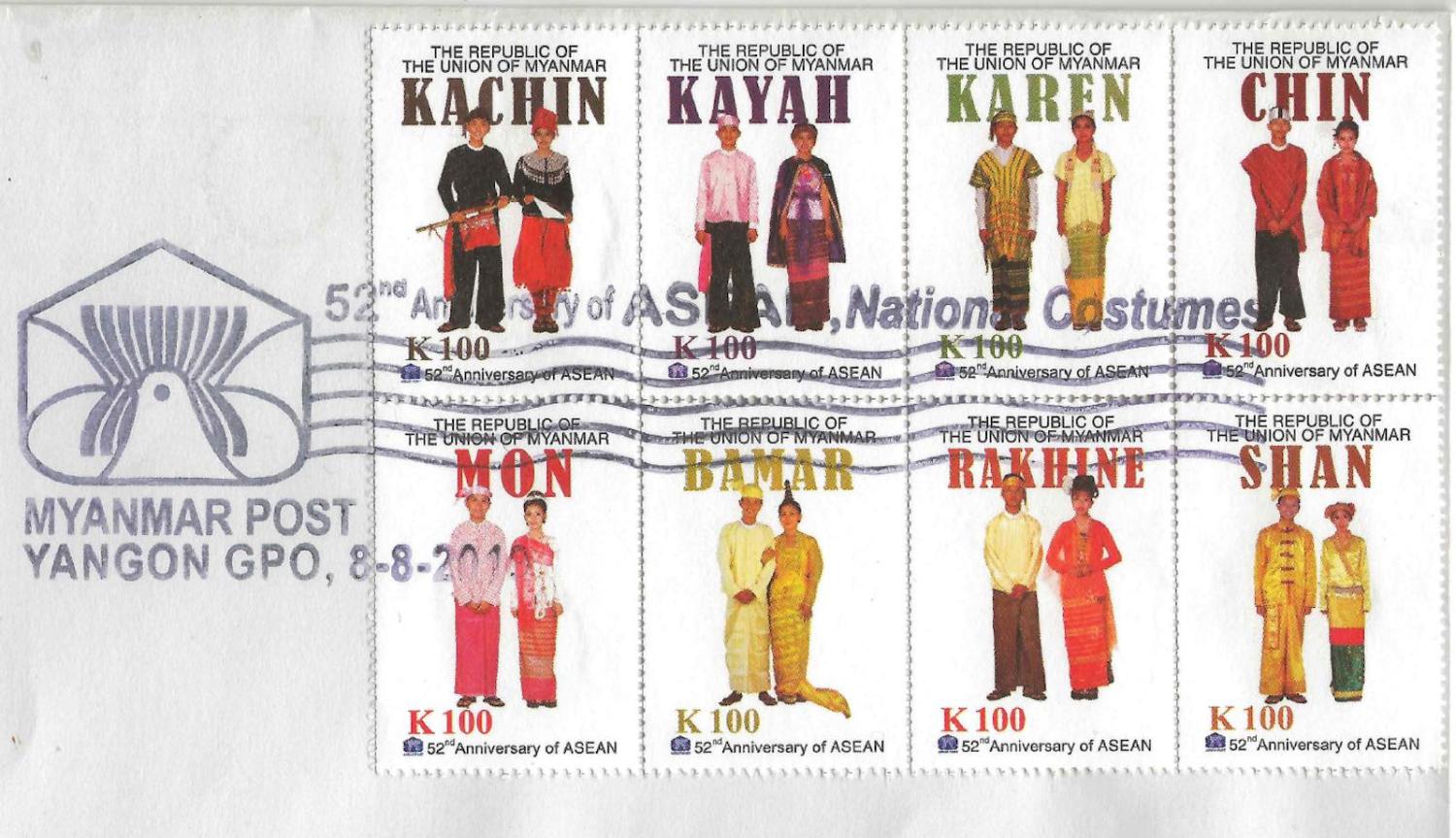

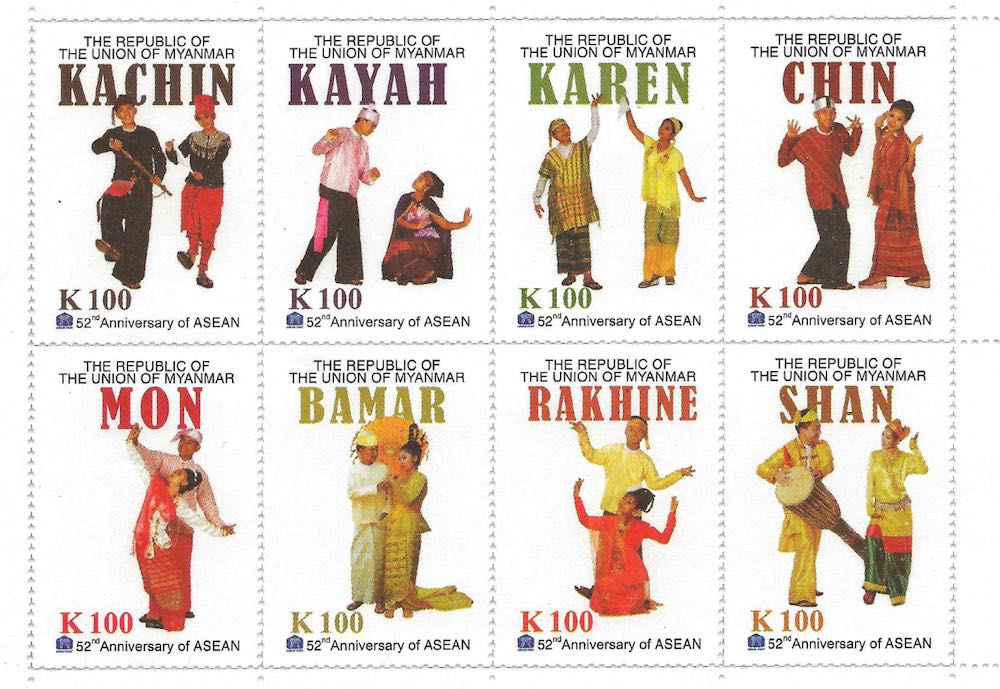

This was suggested recently by the issue of a new set of stamps by Myanmar Post, an agency of the reorganised Ministry of Transport and Communications. In two mini-sheets of eight stamps each, and on the associated first day covers, there are depictions of the country’s eight recognised “national races”, namely the Bamar (Burman), Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen (Kayin), Chin, Mon, Rakhine (Arakanese), and Shan communities.

Myanmar is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world, and the use of such labels to categorise the population has long attracted controversy. The composition and status of the eight races are highly vexed questions. So too is their division by Ne Win’s socialist regime (1962–88) into 135 ethno-linguistic groups. The 8/135 formula, however, is now a well-established part of the official narrative. For example, it was a key component of the 2014 census.

There are precedents for the division of the population in this way. For example, when Myanmar (then known as Burma) regained its independence from Britain in 1948, the first constitution identified the same eight national races. Seven were represented on the national flag by five stars, the Bamar, Mon, and Arakanese being grouped together as one. (There was no star for Kayah State as, technically speaking, it did not join the new Union until 1951).

Also, it was not long before the country was divided into 14 administrative units. There were seven states representing the main ethnic minorities, and seven divisions, covering the areas where the Bamar were seen to be in the majority. Under the 2008 constitution, there are still seven provinces based on ethnic groupings, hence Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Chin, Mon, Rakhine, and Shan States. The seven divisions dominated by the ethnic Bamar are now called regions.

The Rohingya are not recognized as Myanmar citizens, despite the fact that many of them can trace their local roots back for generations.

When a new national flag was introduced in 1974, following the promulgation of a revised constitution, the 14 states and divisions were each represented by a small star, surrounding the gearwheel and rice stalk logo of the Burma Socialist Programme Party. Until a different national flag was introduced in 2010, the old banner figured prominently on the country’s postage stamps, publicly reinforcing the division of the population into eight national races.

The latest stamp issue follows a pattern set by the former military regime. A similar set of stamps was released in 1974, depicting the national costumes of the main ethnic groups. The same eight races were identified. The higher denomination stamps were reissued in 1989 and again in 1990, when the country’s name was changed from the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma back to the Union of Burma, and then to the Union of Myanmar.

That Naypyidaw is using postage stamps for political purposes was also indicated by the issue in 2017 of a stamp depicting Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, who was described not as the country’s independence hero, but as Myanmar’s first foreign minister, a position currently held by his daughter. The stamp was part of a campaign to resurrect Aung San as a political icon and give greater legitimacy to the National League for Democracy administration.

The significance of the latest set of postage stamps is not so much that they follow a pattern set by previous governments, but that they signal clearly to both domestic and international audiences the determination of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government to stand by the 8/135 formula. This effectively rules out the possibility that any other ethnic communities, such as the Muslim Rohingya, might one day be accorded formal status.

The Rohingya are not recognized as Myanmar citizens, despite the fact that many of them can trace their local roots back for generations. If any can prove that their ancestors were resident in Myanmar prior to the first British colonial incursions in 1824, they may be granted a form of citizenship. However, they would still be denied recognition as members of an indigenous ethnic group, with the rights and privileges that status implies.

Indeed, in Myanmar even the term “Rohingya” is avoided. In 2016, for example, Aung San Suu Kyi asked local officials and resident diplomats to refer instead to “people who believe in Islam in Rakhine State”. In 2017, in a historic speech following the military “clearance operations” labelled ethnic cleansing by the UN, she did not use the word “Rohingya” once, referring only to “Muslims in Rakhine State”.

Others in Myanmar, including senior military figures, routinely dismiss the Rohingya as “illegal Bengali immigrants”, or worse.

Countries have been using postage stamps to make political statements since their introduction by the British in 1840. Since 1948, Myanmar has employed stamps to express its sovereignty, project its national identity, promote official policies, and mark important events. In a not very subtle way, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government is continuing this practice, in the latest case implicitly but emphatically denying the Rohingya the recognition, and thus the status, that they crave.