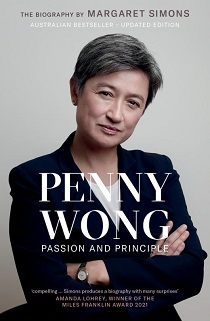

Book review: Penny Wong: Passion and Principle, by Margaret Simons (Black Inc. Updated edition 2023)

Book review: Penny Wong: Passion and Principle, by Margaret Simons (Black Inc. Updated edition 2023)

Contemporary political biography is the art of working out how our leaders made themselves, admittedly with a little help from family and friends, books and mentors, study and travel. Margaret Simons’ updated appraisal of Penny Wong seeks to explain how a guarded, brainy, sharp (in both senses of the word) half-Hakka, gay woman from Sabah could become Australia’s foreign minister.

To judge performance by foreign ministers, we might apply a few simple criteria. Do they single-mindedly pursue Australia’s abiding interests? Do they recognise that the development, economic and trade dimensions of their portfolio matter as much as the diplomatic and strategic elements? Can they work with their prime minister, and make the bureaucratic machinery at their disposal work for them? Are they sufficiently sceptical of confections such as great and powerful friends, like-minded countries or the international community?

With Wong, the answers to those questions remain a work in progress. For her part, Simons focuses elsewhere, with a painstakingly thorough account of Wong at school (”little Penny liked superheroes”), as a trainee politician at university, a union official (including a stint at the Federated Furnishing Trade Society of Australasia), then as Senator (from 2001), shadow Minister (including, at one stage, for accountability) and Minister (for Climate Change and Water, Finance, then Foreign Affairs). Along the way, Simons includes succinct but thoughtful commentary on Wong’s faith, her sensitivity to any hint of racism, even her writing habits.

The woman who emerges is depicted as “principled, intellectual, private, restrained and sane”. For Simons, Wong represents “the embodiment of and an agent for the broadening of Australia’s identity”. As Simons recounts Wong’s development, early comment on some nerdiness and distance give way to an emphatic endorsement of Wong’s performance so far in the Albanese government. “Transformational” “activism” is awarded high marks. “Perhaps Wong will even have contributed to avoiding war.”

How, though, does what Wong was help us understand how she will perform as foreign minister? Simons pays attention to Wong’s early plans to work with Médecins sans Frontières and her gap year in Brazil, but focuses much more heavily on the Senator’s first speech to parliament. Public servants are often encouraged to read their Ministers’ first speeches, in the belief that they will find not just personal detail but clues to what actually matters to the Minister concerned. In Wong’s case, that speech comprises a testament to the vehemence of her views on racism.

Toughness, pragmatism and ambition are all evident in Simons’ exhaustive re-runs of Australian Labor Party squabbling and jockeying, whether for top spot on a ticket, on same-sex marriage or in picking leaders. Wong’s use of “counter-factual” argument and her respect for “praxis” (here interpreted as jobs invested with meaning) are underlined, as is the wisdom of her remark that, for countries like Australia, “first-mover advantage lies with whoever sets the agenda”.