A year after announcing Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), Indonesia and Vietnam were back at COP28 climate negotiations in Dubai, with investment plans to bring the partnerships to life. JETPs have been referred to as “gamechangers” when it comes to help industrialised economies such as Indonesia and Vietnam wean off coal in a just and equitable manner. But the investment plans for Vietnam and Indonesia share a common challenge: insufficient public finance to catalyse large-scale private investment.

According to the investment plans, the estimated total sum required to decarbonise Indonesia’s on-grid power sector is US$96.1 billion until 2030. Decarbonising Vietnam’s power sector – generation and transmission – could come in even higher at US$134.7 billion.

In Indonesia and Vietnam respectively, existing commitments only contribute to 21% and 11% of total sum required. The rest relies on the ability of JETPs to catalyse further investment.

The high dollar private finance expectations for JETPs been quashed by the realities of global rising interest rates and grant conditionality of international public finance. Grants including technical assistance only account for 2.6% for Indonesia of existing commitments from the International Partners Group, which comprises the European Union, United Kingdom, United States, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, Denmark and Norway. Around 4% is committed for Vietnam.

This small proportion of grants might be the biggest hurdle in securing private financing and project bankability, as JETPs’ ability to catalyse further investment will then rely on available domestic public finance and the willingness from governments to borrow, even at concessional rates. This reliance poses several challenges as both countries have competing national priorities. With GDP per capita still below US$5,000 per year, health, education, basic infrastructure and social protection are strongly focused.

Additionally, Vietnam will need significant financing for their US$70 billion high-speed rail project, while Indonesia has several large infrastructure projects underway, including a new capital city, Nusantara, with a price tag of US$29.6 billion equivalent.

Prioritising domestic public finance to facilitate the implementation JETPs does not appear to be high on political agenda, as government leaders, such as Indonesian Minister Luhut Pandjaitan, still sees the current JETP’s offers as “adding significant financial burden” to the state envelopes.

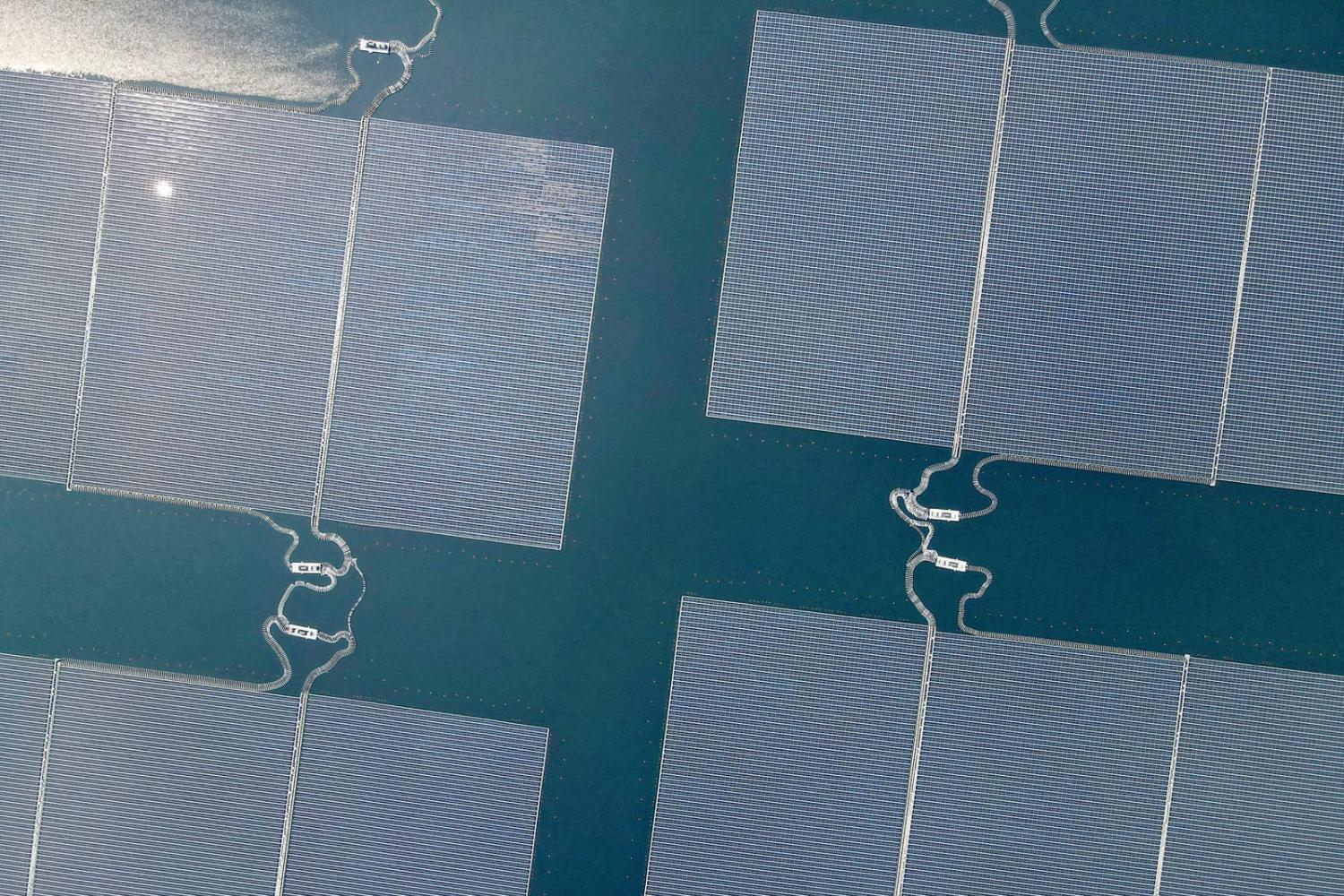

Against this backdrop, where JETPs could be more effective is in support of programs that facilitate economic transition to secure initial quick wins and build on momentum for successful implementation. Supporting renewable manufacturing industries is one example, as both countries are well positioned to contribute to global supply chains for low-carbon technology. Indonesia and Vietnam’s JETP investment plans reference this potential.

As ASEAN members, they benefit from favourable trade terms through the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA). Indonesia and Vietnam could establish an intra-regional ecosystem to foster low-carbon technology manufacturing and consumption, at scale. Recent visits from Vietnamese and Indonesian leaders resulted in commitments from both sides to establish partnerships for electric vehicles and battery storage industry.

A strong manufacturing industry is high on the agenda and could drive public support and funding for national and regional economic growth. Additionally, as local industries develop, policy makers have a stronger case to enact policies to create domestic demands and enable the growth of the industries in the emerging phase. This strong domestic support will ultimately help accelerate coal phase out and increase renewable energy uptake at scale.

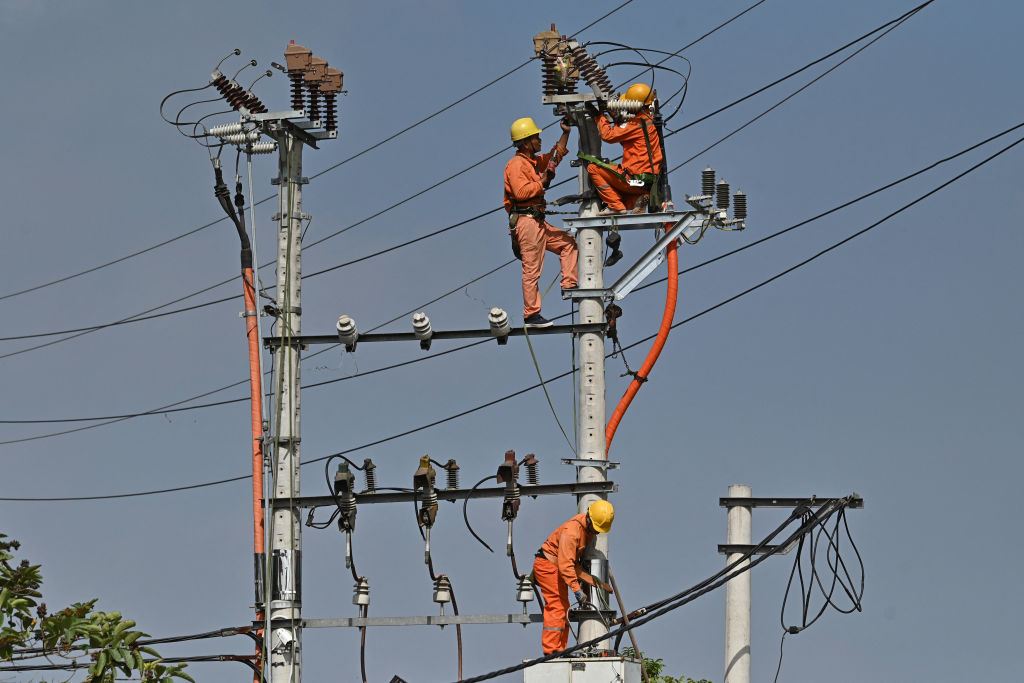

Both countries note opportunities to transform their labour force in their JETP plans. Indonesia’s plan estimates 383,000 jobs will be created in Indonesia by 2030, with a large proportion of managerial, technical and high-skilled professionals. To meet this demand in a short timeframe, it requires a holistic transformation to education and training at all levels. Supporting green skill adoption and workforce development could also help attract investment, providing a stronger case for policy makers to accelerate Net Zero policies.

The International Partners Group can play a role in aligning internal development objectives with other international partners to ensure bilateral programs align with JETP’s objectives. Diverging climate policies and international development objectives can stymie climate action. There are several initiatives that provide rationale for these alignments, such as the G7 Climate Club, of which Australia is a member.

The Australian government announced plans to support energy transitions in Indonesia and Vietnam – an opportunity to align the objectives of these bilateral programs to JETP targets. As the world is undergoing critical geopolitical challenges, it is more important than ever before that international community to come together and demonstrate a complementary approach to international development.

JETPs have not lost their “gamechanger” potential just yet, but in the next ten months leading to COP29 in Baku, the world will look for some initial successes to drive the momentum. These successes will hinge on securing additional finance, domestically and internationally, through prioritising solutions that align net zero objectives with social economic transition and international climate diplomacy goals.