Remember when Australia used to refer to its near neighbours in the region as the “arc of instability”? The leadership shenanigans on Tuesday will have given the BBC’s former Australia correspondent Nick Bryant an opportunity to update his description of Canberra as the “coup capital of the democratic world”.

Been on the subway for a couple of stops. Is Malcolm Turnbull still the prime minister? #auspol

— Nick Bryant (@NickBryantNY) August 21, 2018

The “arc” of nations to Australia’s north and east look comparatively boring when it comes to politics. None more so than Papua New Guinea, which once upon a time was the nation most often cited when it came to political putsches.

Since the turn of the century, PNG has taken the lead on political stability. A quick analysis of prime ministerial terms shows that a PNG prime minister over the past two decades has spent – on average – more than 40% more time in the top job than their Australian counterpart.

PNG has had four PMs during that period: Bill Skate, Sir Mekere Morauta, Sir Michael Somare and Peter O’Neill.

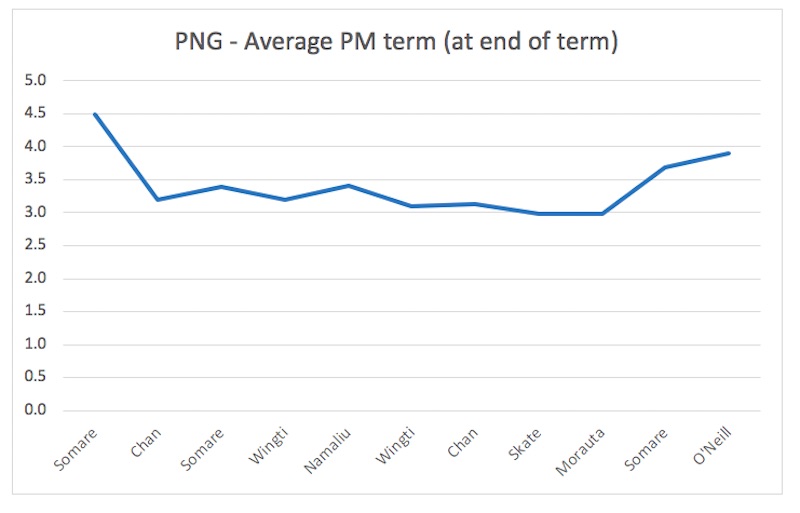

When Skate became Prime Minister in 1997, his predecessors since independence in 1975 had served an average of 3.1 years in office. Skate didn’t last that long – he was ousted just two years later. But his successors have wrangled and finagled their way to remarkably resilient careers since then.

Peter O’Neill’s return to government after last year’s election means the average term for a PNG PM since independence is up to 3.9 years.

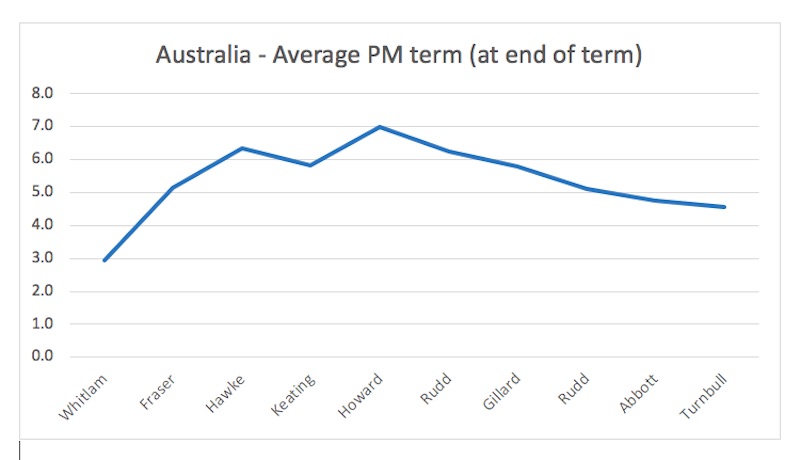

In Australia, when John Howard became prime minister in 1996, his predecessors from 1975 – including Gough Whitlam – had served an average of 5.8 years in office. Howard himself managed 11.7 years in the top job, but since then the revolving door in Canberra has reduced the average down to 4.6 years for each prime ministerial term since 1975.

PNG’s political system still has its challenges: of the four PMs from the past 20 years, two of them (Somare and O’Neill) both claimed to be PM at the same time for a period in 2011 and 2012. Australia hasn’t managed a constitutional crisis – yet – on that level.

But the statistics paint a picture of prime ministerships in Australia being an increasingly short-run career. Perhaps it’s time for Australia’s political leaders to get some advice on longevity from their PNG counterparts?