Dron Parashar, writing in The Interpreter last month, notes that other countries are actively exploring nuclear options for electricity generation, while the current Australian strategy has no place for nuclear. But his argument ignores the key issue: Australia’s special advantage of cheap and abundant solar clearly dominates the much higher cost of any nuclear option.

For countries without Australia’s unique opportunities for solar, nuclear may well make sense. Japan has no room for solar. Europe has too many cloudy, rainy days. But for Australia, during the critical transition period over the next few decades, the efficient pathway is a combination of solar/wind with batteries, with gas to handle the increasingly rare times when peaking power will be needed.

Let’s put to one side the vexed arguments about safety, disposal of spent fuel, decommissioning and so on, and focus just on the issue of cost. The CSIRO comes down clearly against nuclear. You can argue the details, but the differential is so overwhelming that it’s not even close. Solar wins.

Let’s look at the specifics of current nuclear experience.

There are two technologies: conventional large-scale reactors or the increasingly fashionable technology of the future, Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

If Australia had installed a lot of conventional nuclear plants during the 1960s and 70s (like France or Japan), their operational life could be extended at modest cost, which makes this relevant for the transition. But Australia didn’t, so it isn’t.

We would build from scratch. There is a huge difference between the building costs in China (where around 30 reactors are under construction) and in economies like Australia’s, hemmed in by regulation, work practices and “not-in-my-backyard” opposition. This (pro-nuclear) article sets out the wide range of construction costs.

For Australia, the case studies of China (or even South Korea) are not relevant. Australia is more like the United Kingdom, which is struggling to get enough new reactors built to replace the existing ones as they pass their use-by dates. Hinkley Point is the current exemplar. Construction began in 2016: completion predictions, currently early next decade, recede with every reappraisal. The cost, originally estimated at £18 billion, is likely to be double that figure or more. This is for a reactor with an output not much higher than Australia’s coal-fired Eraring, so quite a few of them would be needed to replace Australia’s existing coal generation. And Hinkley Point is on an existing nuclear site, bypassing potential NIMBY opposition.

The UK government has given the operator a price guarantee, which in 2016 was officially estimated to cost consumers/taxpayers £50 billion. Even so, the very experienced French contractor is reluctant to sign up for the next planned reactor.

Of course we could hope to do better than this debacle, but substantial cost and time over-runs are the norm, unless Australia opts for a Chinese or South Korean turn-key project using foreign workers with their own technology. Is Australia ready for that?

The hope of many nuclear proponents is now focused on SMRs. These are much smaller reactors, to be built off-site in factories to a standard design, promising major cost savings.

There are just two operational SMRs, both research reactors. Many competing designs for a commercial reactor are under regulatory consideration. Attention has been focused on the Idaho NuScale proposal, which was expected to be the first operational commercial SMR, with all the regulatory hurdles cleared.

But despite US$1.4 billion in government support and the promise of a further 3¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh) subsidy available from the Inflation Reduction Act, this project has been halted as the revised cost per kWh is uneconomic for the distributors who had signed up as customers.

Countries without Australia’s sunny skies and abundant land will have to wear the cost of much more expensive electricity from nuclear, either conventional or SMRs. There may well be a role for SMRs in Australia in the longer-term future, perhaps for remote locations. But it is sensible to let others do the expensive early-stage development of a technology that at best will only be marginal in Australia’s supply array.

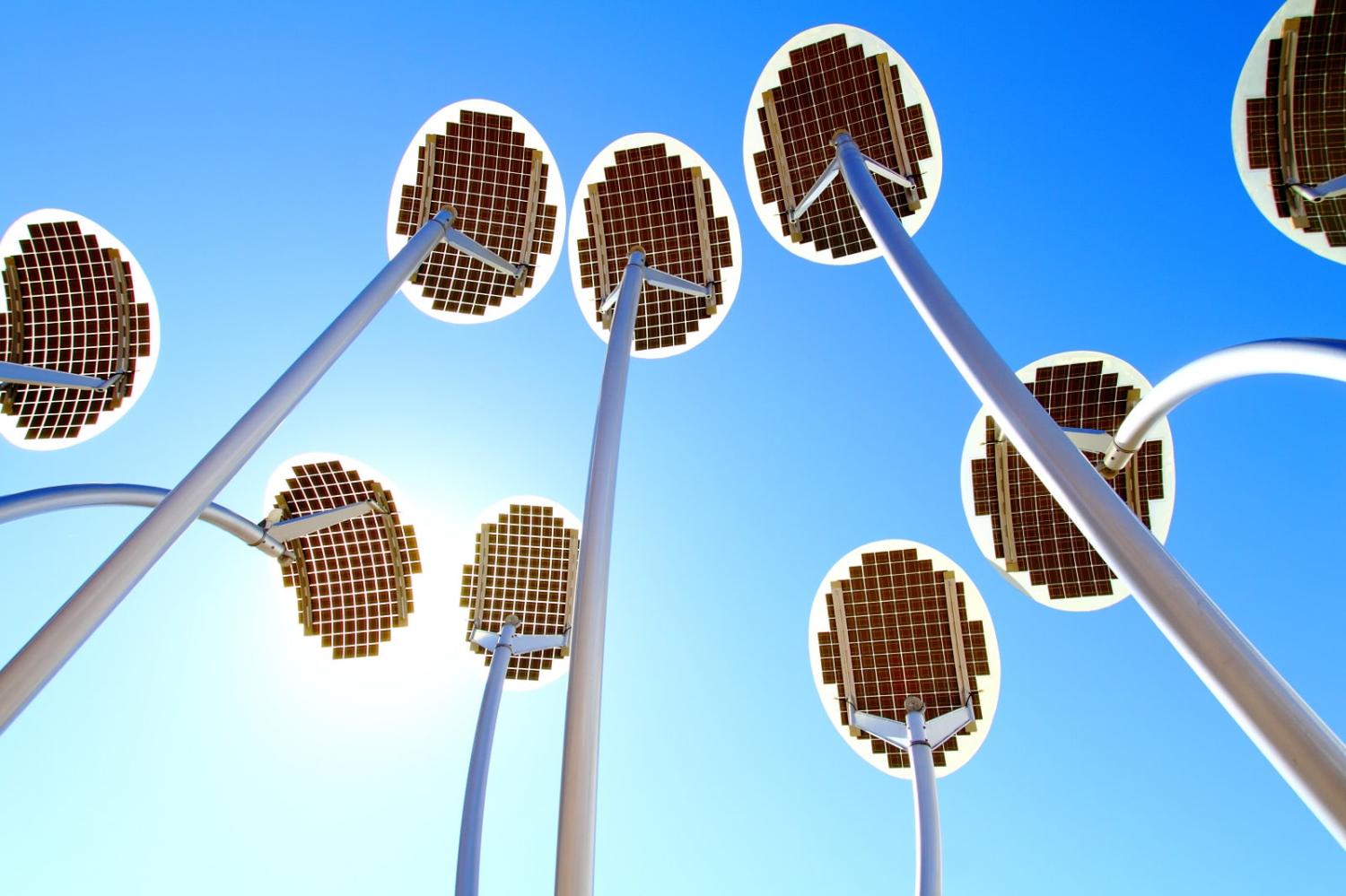

The relevant opportunities and challenges for Australia lie in building its comparative advantage in solar. One vision for the way forward is given by Ross Garnaut’s Superpower. Using solar to refine steel and aluminium, and to generate hydrogen, Australia could lead the world in using solar for the full range of production, which must be decarbonised if we are to reach zero by 2050.

For those with a more modest vision, it might be enough to chart the way forward towards the Australian government’s 2030 renewables target, which is largely about replacing coal in electricity generation. Whatever the longer-term role for nuclear in Australia, it cannot make any contribution to achieving the 2030 target and, even under the most optimistic projections, would be relevant only after 2040.

Given the die-hard opposition in some sectors, excluding nuclear from the current options seems sensible politics. Why stir a hornet’s nest that is irrelevant to the immediate challenge? It will be a stretch to get there even if we go at warp-speed with readily available technology.

In the facts-lite political debate, it is hard to tell whether the nuclear proponents really believe their own case, or just want to throw up enough dust and delay so that coal generation continues for longer and we fall far short of the 2030 and 2050 targets.