SpaceX may be the highest-profile player in the race to commercialise Space, but it is certainly not the only one. In 2021, the global Space economy was estimated at more than US$490 billion in what is set to become a trillion-dollar industry. More than 1000 new Spacecraft in orbit were observed during the first half of 2022 alone. The global trend indicates that risk-taking and hyper-entrepreneurial New Space (private Space industry) entities are likely to be the leaders in the next phase of the Space race.

SpaceX, for instance, eventually aims to have 42,000 satellites in Space to create its Starlink mega-constellation and multiple companies offering services in Space tourism. These types of movements largely originate from the “left coast” of Silicon Valley and other fertile start-up environments.

However, not all developed countries offer such conducive conditions, including the institutional environments of East Asia, home to the world's second and third-largest economies. For the governments of these countries, the question is which approach they should adopt towards the new and risk-taking companies trying to establish themselves in the Space economy. Should they hold back, regulate, manage, enable, or take a path of non-intervention?

The relationship between governments and Space commercialisation is closely tied to the challenges of humanity's engagement in Space and the exacerbating environment caused by the largely ungoverned nature of human activity in Space. The historic international treaties on Space, including the Outer Space Treaty (1967) and the Moon Agreement (1979), set the framework for transnational cooperation in Space by preventing individual states from seeking national appropriation and claiming the sovereignty of celestial bodies. However, the limitation of these historical treaties, which dealt with the competition between superpowers during the Cold War, is that they did not anticipate the emergence of non-state actors – mainly commercial and profit-driven players – nor did the frameworks extend to sustainably coexist with New Space entities.

Japan takes the approach that the state gains rights indirectly by legally authorising the activities of domestic companies in Space, much as the United States does. The US Space Act (2015) states, “The President, acting through appropriate federal agencies, [shall] facilitate commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of Space resources by US citizens.” In Japan, the Act on the Promotion of Business Activities for the Exploration and Development of Space Resources (Space Resources Act) came into force in 2021. Under the Act, a Japanese private lunar exploration company recently received a license to conduct business activities on the Moon.

While the Japanese government has become an active promoter of Space businesses, Beijing has taken a different approach, publishing a white paper titled China's Space Program: A 2021 Perspective. It states, “The mission of China’s Space program is [to…] protect China’s national rights and interests, and build up its overall strength” and “China’s Space industry is subject to and serves the overall national strategy.” The white paper also indicates that the Chinese government’s role and relations with Space business activities are centered on regulation and management.

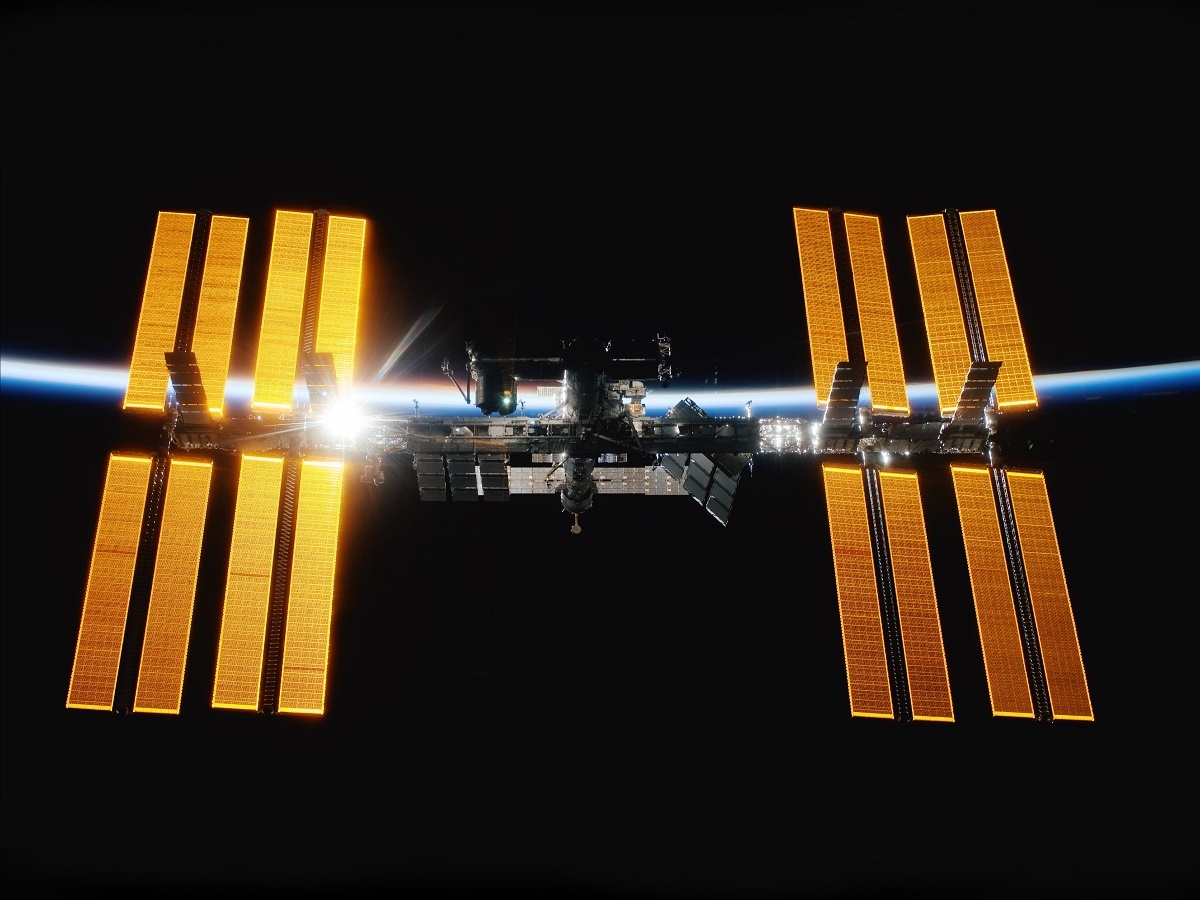

Between “Old Space”, where government organisations drive the supply and demand of the Space industry, and “New Space”, represented by the activity of private entities, South Korean Space companies view themselves as operating in “Mid Space” – where government-dominated demand is met by expanding supply from private entities. South Korea demonstrated its progress last year by deploying multiple satellites into orbit. These multiple versions of Space currently allow for a wide spectrum of global approaches to the industry – from the strictly Chinese-made and managed Tiangong permanent Space station to the collaborative US-led International Space Station.

East Asian governments have so far not aligned on whether to restrict or enable New Space players. However, the common thread is that East Asian government policies are a critical factor in determining the future of the region’s Space industry. The unrivalled growth of private enterprise in this area has led to what is being called the “technopolar moment” in which digital powers reshape the global order. However, East Asia offers an example of the enduring power and role of government, one where the Government-Space business relationship is well positioned to ensure the industry's growth is sustainable, not just driven by private interests.

The expansion of activity in outer Space brings with it myriad issues that increase the risks to humanity, including the dangers associated with Space debris. With Virgin Galactic offering Space travel for US$450,000 and Starlink satellite internet coverage costing less than AU$500, the commercialisation of outer Space inevitably raises questions about the benefit-cost ratio to humanity. Interdisciplinary efforts among academia, international business and global security experts are needed to bridge the gap between governments, industry leaders and entrepreneurs.

If Australia is to become a significant player in the second Space race, it must continue to bolster its relationships with partners in the Indo-Pacific so that it can renew and strengthen ties with East Asia to realise its ambitions in Space.