After the Houthi–Saleh coalition collapsed and former President Ali Abdullah Saleh was killed in December, it didn’t seem as though the conflict in Yemen could get any more complicated. Barely two months later, however, another one of Yemen’s coalitions has imploded.

On 27 January, intense fighting broke out between units loyal to Yemeni President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and those backing the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a political body dedicated to the re-emergence of an independent South Yemen. This followed the STC’s 21 January demand that Hadi replace his prime minister and cabinet. By 1 February it was clear the separatists had gained the upper hand – most of the forces loyal to Hadi had either surrendered or were confined to a small strip of territory surrounding the Presidential Palace.

The recent fighting marks the latest escalation in a political struggle that has raged between the STC, led by Aidarous al-Zubaidi, and the government of President Hadi.

The driving force behind the STC is the Southern Movement, known colloquially as al-Hirak, a disparate yet popular separatist movement in south Yemen. Originally formed in 2007, the Southern Movement has gained significant momentum due to its role in driving Houthi forces out of Aden in 2015. Since then, a complex and competing array of security forces have coexisted in Aden. These include the UAE-backed Security Belt forces, many which are loyal to the Southern Movement, as well as the Presidential Protection units, largely loyal to President Hadi.

Over the past two years, tensions between these groups has escalated. In February last year, fighting broke out at Aden airport. Another escalation occurred in late April when President Hadi sacked Zubaidi, the governor of Aden at the time, as well as Minister of State Hani bin Breik. In May, in response to the sacking, Zubaidi and bin Breik announced the formation of the STC, whose purpose was to prepare the ground for the eventual independence of South Yemen. Throughout 2017, Hadi’s control over the south continued to deteriorate.

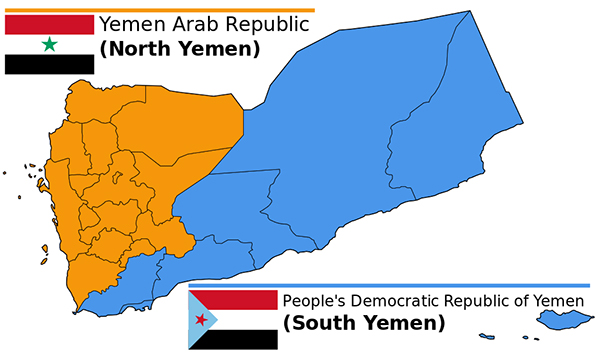

The borders of North Yemen and South Yemen prior to unifcation in 1990 (Map: Wikimedia)

The role of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia is important to understanding these recent events. While the UAE is the junior partner in the Saudi-led coalition intervention in Yemen, it has been busy consolidating what it considers its strategic interests in the southern Yemeni coastal governorates. This includes the setting up of parallel security institutions outside the framework of the Yemeni state. Because of this, many Yemenis have come to view the recent events in Aden as part of UAE-led efforts to divide Yemen, and of divisions within the Saudi-led coalition itself.

Although it has empowered southern actors, the UAE is unlikely to have risked playing a direct role in the recent events for fear of angering Saudi Arabia. Rather, the UAE’s support of armed groups functioning outside the Hadi government should be viewed as motivated by a pragmatic understanding of the limitations of that government, rather than as a clear intention to divide Yemen in two.

For its part, Saudi Arabia is likely to be extremely unhappy with recent events, despite reportedly losing patience with the Hadi government. At the very least, the events in Aden completely eclipsed a recent PR push on Yemen based on a US$2 billion deposit into its central bank, as well as a US$1.5 billion commitment of humanitarian aid.

Reducing these events to geopolitical manoeuvring does a disservice to the genuine anger many Yemenis in the south hold against the Hadi government. Despite its liberation from the Houthis in 2015, Aden continues to be plagued by a poor security environment; the presence of terrorist groups, such as al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and Islamic State; and a non-functional judicial system dominated by armed groups.

In addition, public services, most notably the energy and health sectors, have been consistently degraded. Many blame high fuel prices on the corruption of businessmen close to Hadi himself. A large number of public sector wages have not been paid in months, and the Yemeni rial has continued to depreciate, damaging the purchasing power of Yemenis in a country that imports the vast majority of its food.

The recent events have made clear the extent to which the legitimacy of the Hadi government has been eroded. This is no better emphasised than by the fact Hadi has not visited Yemen since February 2017. Although it is unclear what the full ramifications of events in Aden will be, they will mark a major setback for the Saudi-led coalition campaign against the Houthis, and play into the Houthi leadership’s perception that to triumph they only need to continue to fight a war of attrition.

One thing is evident: the spectre of a divided Yemen is one step closer. Less clear is whether this would improve the well-being of Yemenis currently enduring the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.