Thailand emerged from the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic as one of the best performing countries in the world in terms of minimising cases and deaths. But 2021 has been a different story.

A surge in infections since the beginning of April has seen thousands of new cases each day and a spike in deaths. While authorities moved to close parks, gyms and cinemas (although shopping malls stayed open), mandated face masks in public and tightened quarantine requirements for travellers, the virus was already rampant in settings where social distancing wasn’t possible, including the country’s notoriously overcrowded prisons.

More than 17,000 people in prison have contracted Covid-19 in this third wave in Thailand, and the tally is rising daily. On 25 May, the Thai health ministry reported 882 new cases in prisons in the preceding 24 hours (alongside more than 2300 new cases among the general population). Prisons across greater Bangkok have been hit particularly hard, but cases have also been reported at prisons in Narathiwat in the south and Chiang Mai in the north.

As of 17 May, people in prison made up more than 70% of the 9635 new cases reported nationally that day. At one prison in Chiang Mai, some 61% of offenders tested positive.

It takes little imagination to comprehend the heightened health risks faced by people detained amid a global pandemic. Unsafe and unsanitary conditions, poor ventilation, overcrowding and limited access to health services are issues in prisons around the world, and the physical and mental health of people in prisons is typically well below those living on the outside. Infections may be spread within and between prisons through new admissions, prisoner transfers, visits and staff deployments across multiple prisons, affecting people in prison, staff and the community.

Serious Covid-19 outbreaks have been reported in prisons in India, Pakistan, South Africa, South Korea and the United Kingdom, to name a few. In the United States alone, as of 18 May, just under 398,000 people in prison had tested positive, with an estimated 2680 deaths, according to The Marshall Project, a not-for-profit group focused on reporting on the US criminal justice system. The figures are even higher when accounting for people across all detention settings, as tracked by the New York Times.

In Thailand, which has consistently had one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, the risk of an outbreak was always high. With a total prison population currently estimated at over 307,000 – three times larger than the country’s official prison capacity – Thai prisons are chronically overcrowded. At one facility, the Thailand Institute of Justice recently reported that 35–45 people were forced to share a single cell, sleeping shoulder to shoulder. The country’s strict drug laws are a key factor fuelling imprisonment rates, with more than 80% of people estimated to be detained on drug-related offences.

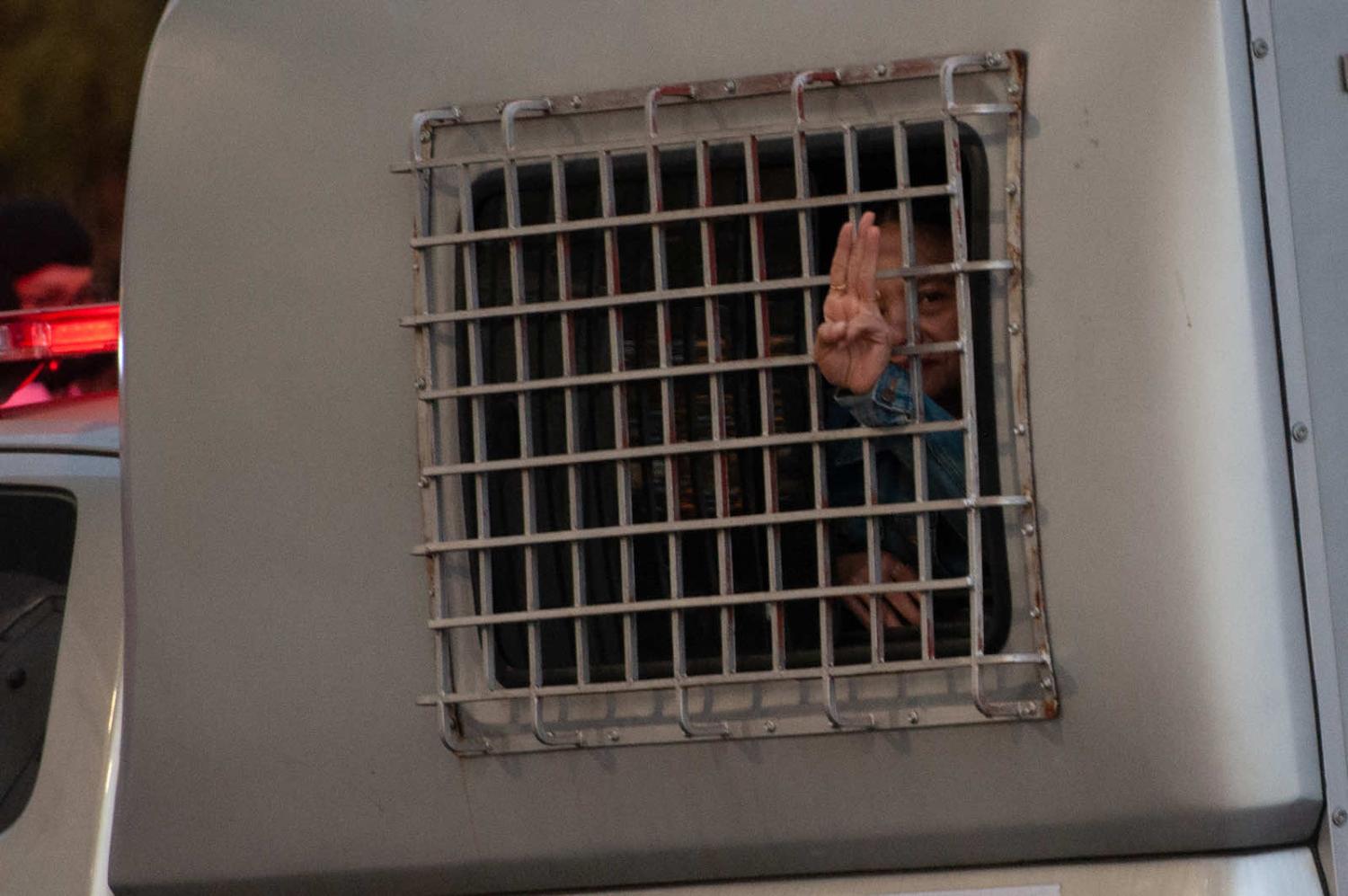

The full scale of the current outbreak in Thailand’s prisons was only brought to light after several prominent student activists involved in anti-government protests last year, and detained on charges of insulting the king, revealed they had tested positive to the virus. Among those infected were Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul, who made headlines last year after publicly calling for reform of the monarchy, human rights lawyer Arnon Nampa, and several others who are now out on bail.

Although Thailand’s prison population has in fact declined over the past year, this has clearly done little to alleviate chronic overcrowding, or to ameliorate the health risks for people detained.

After being slow to act, Thai authorities are now scrambling to respond. Measures flagged to address the outbreak across multiple prisons include the ramping up of testing and vaccinations for people detained, an increase to the quarantine period for new prisoners to 21 days, a halt to prison transfers and consideration given to the early release of 50,000 people. Prison authorities were also instructed to establish field hospitals to treat patients.

However, few officials are sounding optimistic. “Prisons are overcrowded,” Aryut Sinthoppan, director-general of the corrections department, told reporters this month. “So there are limitations to hygiene and disease control efforts.”

Although Thailand’s prison population has in fact declined over the past year (by 16%, according to one estimate) as a result of two mass releases in 2020, this has clearly done little to alleviate chronic overcrowding, or to ameliorate the health risks for people detained.

Prisons are not the only sites that have seen major outbreaks during this third wave. Factories and construction workers’ camps that include many migrant workers, as well as dense urban communities without adequate housing, have also been disproportionately affected. More than 2000 cases were detected at a single factory in Phetchaburi, south-west of Bangkok, more than half of whom are migrant workers from Myanmar.

Thailand’s vaccine roll-out is also attracting widespread criticism, with concerns over supply and distribution, and the urgent need to vaccinate people most at risk. An estimated 1.94 million people have received at least one Covid vaccine dose (either AstraZeneca or Sinovac) to date. Prime Minister and former coup leader Prayuth Chan-ocha is one of the lucky ones – earlier this week, he posed for the cameras with his vaccination certificate after receiving his second dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine.