Opposition foreign affairs spokeswoman Penny Wong’s efforts to set out a vision for Australia’s foreign policy on Asia, embodied in Labor’s “FutureAsia” plans, are admirable. The specific focus of fostering knowledge of and engagement with Southeast Asia is welcome.

A key part of enhancing Southeast Asia knowledge capability is investing in languages, with Indonesian being the most obvious example. Australia needs to begin by taking positive steps to address the image problem of Indonesia that affects interest in Indonesian language studies.

Australia needs to begin by taking positive steps to address the image problem of Indonesia that affects interest in Indonesian language studies.

Several years ago, I taught Indonesian in a primary school and high school in Victoria. In the classroom, I was confronted by my students’ negative perceptions of Indonesia. I had assumed that students might want to study Indonesian, at the very least in the hopes of going on a future holiday to Bali and learning how to bargain in the markets.

Instead, it was clear that the vague understanding many students had about Indonesia came through exposure to negative Australian media or their parents’ views.

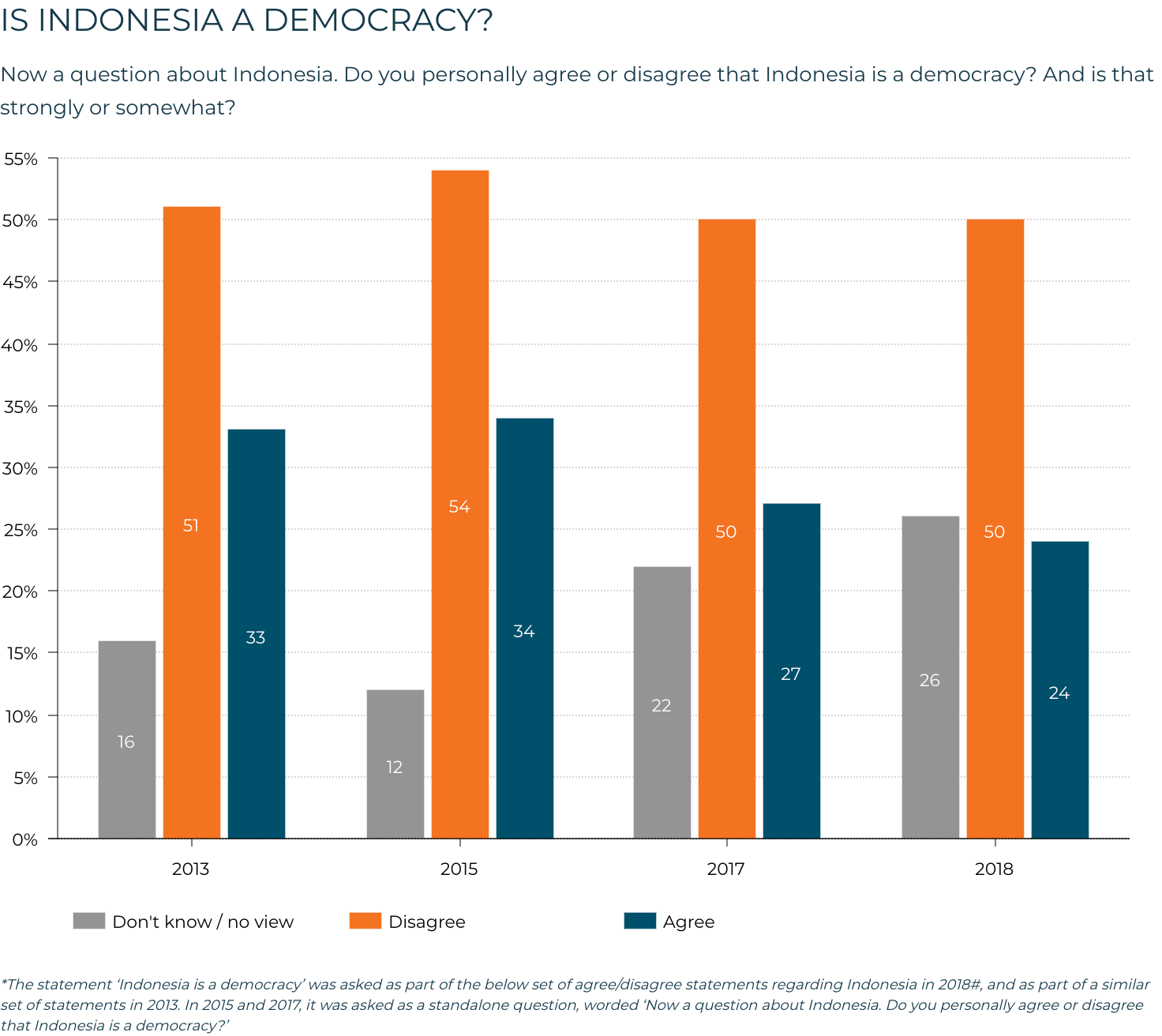

A lack of knowledge on basic facts contributes to these misperceptions. For example, as a Lowy Institute survey found, most Australians are not aware that Indonesia is a democracy. Since 2015, the number of people surveyed who correctly answered that Indonesia is a democracy has dropped by 10%.

Basic facts about Indonesia should be common knowledge in Australia, because it affects the attitudes people have towards Indonesia.

In my former role as a primary school teacher, I had an 11-year-old student tell me that they didn’t want to learn Indonesian because their mum and dad said that Indonesians are terrorists. It’s pretty hard to reason with an 11-year-old when extensive media coverage of terrorism, general public perceptions and perhaps even their own parents might support this false stereotype.

In addition to the image problem, Australia needs to radically overhaul and reinvest in institutional support for Indonesian studies.

Daily, I live through the consequences caused when universities make fatal decisions to cancel their Indonesian language programs, as a number of universities in Australia have done. These decisions are made, in part, because of the broader absence of a social, economic and political ecosystem in Australia that supports Indonesian studies.

Seriously low numbers of primary and high school uptake in Indonesian create negative downstream consequences for higher education institutions. In turn, the scale of Asian language programs in primary schools and high schools across Australia affects enrolments in languages at university.

In my high school, there were just five students in the Year 12 Indonesian class. When high schools choose to axe their Indonesian program, as in fact my old high school later did, this has major flow on effects for universities.

Language programs often depend upon on a steady number of students in the intermediate to advanced language classes. Without strong numbers of students graduating from high school having studied Indonesian language, the potential pool of students who go on to study Indonesian at university diminishes rapidly. When there are so few university students choosing to study Indonesian, this presents challenges for the viability of university programs.

But I also see the opposite problem. On my campus, I come across students who want to study Indonesian, but can’t. While studying and gaining credit through another university is theoretically possible, its often a logistical impossibility because of the challenges that students face to coordinate classes at two different universities and campuses.

As a result, some students that I know who learnt Indonesian in high school stopped studying Indonesian. This is an incredible waste of talent and interest in Indonesia.

So what can be done? Penny Wong’s vision on greater engagement with Southeast Asia is admirable but needs to be backed up with a long-term plan to enhance both general and specialist knowledge of the region.

Any major effort to make Indonesian studies a national priority in Australia would require a holistic approach. The government must take the initiative and acknowledge its role as an important driver of incentives for change. This includes incentives for students to choose Asian languages and support for universities to maintain or enhance their Asian language programs.

Shifting the dire predicament of Indonesian language studies in Australia in my lifetime will require a fundamental change in direction for the education sector across the board - primary schools, high schools and universities.

Its time for the next Australian government to reverse the Indonesian language disaster on our shores. After all, the “Asian Century” really should be the time to start learning an Asian language.