The signing of a treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste marking maritime boundaries in the Timor Sea represents a huge step forward in resolving the two states’ long-standing disputes. The conciliation process that led to the agreement was groundbreaking for being the first time such an approach has been used under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

This is not, however, the end of the story, despite recent media reports to the contrary. In fact, Timor-Leste and Australia has not fully resolved the Timor Sea dispute for three key reasons.

More negotiations flagged

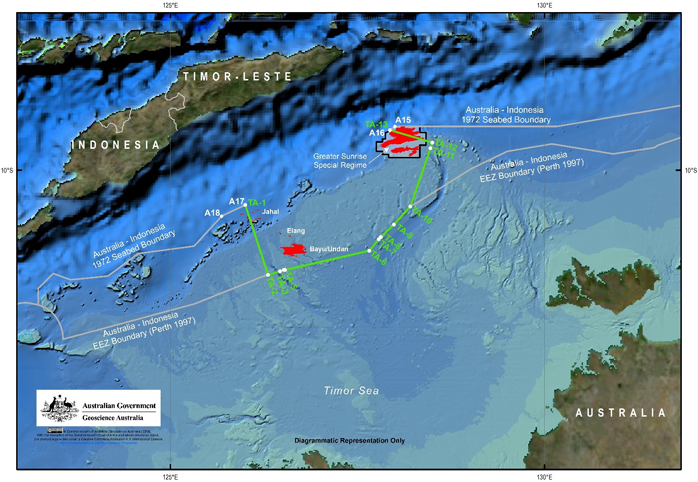

First, the new treaty defines boundaries distinct from the limits of the existing joint petroleum development area (JPDA), ), which will cease to exist once the new treaty comes into effect. This zone (see map) was defined under the Timor Sea Treaty, signed between Australia and Timor-Leste on the day the latter gained independence.

The boundary between opposite coasts in the central part of the Timor Sea is a fairly conventional “single” maritime boundary broadly consistent with the median line defining the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf rights. While it is favourable to Timor-Leste, the new treaty offers little material benefit.

It does, however, represent a notable symbolic victory for Timor-Leste, which has long campaigned for the adoption of a middle line in the Timor Sea. The boundaries had become increasingly politicised and linked to “sovereignty” and identity, representative of Timor’s statehood and independence.

Importantly, the lateral lines of the new agreement connect with the pre-existing 1972 continental shelf boundary between Australia and Indonesia. This means that Australia and Timor-Leste’s new boundary arrangements do not prejudice Indonesia’s rights or jeopardise Australia’s existing boundaries with Indonesia.

Taking a highly innovative approach, Australia and Timor-Leste have devised the lateral boundary lines in such a way that they are capable of adjustment in the future. This will only occur should Indonesia and Timor-Leste reach agreement on widening Timor-Leste’s “window” on the Timor Sea, thus redefining the Timor Gap. Any such readjustment will also only take place once the resources of Greater Sunrise have been exploited, in an arrangement designed to provide certainty to the oil companies involved.

This means that future negotiations may need to occur.

Indonesia waiting

Second, Timor-Leste has yet to strike an agreement on its maritime boundaries with Indonesia. Portions of the lateral lines in the Timor Sea nearer Timor-Leste’s shore need to be settled, and also potential boundary lines between the northern coast of Timor-Leste and Indonesian islands across the Wetar Strait. Additionally, Timor-Leste’s Oecusse enclave, surrounded on the landward side be Indonesian west Timor, but with a coastal front to the north onto the Ombai Strait is likely to be a tricky issue in negotiations, situated as it is within Indonesia’s archipelagic baselines.

Although bilateral boundary negotiations were initiated in late 2015, agreements are yet to be concluded. Even if all of Timor-Leste’s maritime boundaries are settled, ongoing cross-boundary cooperation will be necessary to ensure good oceans governance and regional peace and security.

Greater Sunrise unresolved

Third, and most critical for Timor-Leste economically, is the issue of the actual development of the lucrative Greater Sunrise complex of fields, and how its revenues will be split. This is key to Timor-Leste’s economic future. Here, the agreement contemplates different “development concepts”, including whether the pipeline from Greater Sunrise goes to Australia or Timor-Leste – a decision which will inevitably impact on benefits downstream.

If the pipeline runs to Timor-Leste, the country would receive 80% of government revenues arising from the development. If the destination is Australia, Timor-Leste would receive 70% of proceeds from Greater Sunrise. Either way, this represents an improvement for Timor-Leste on the 50/50 split outlined in the previous Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS).

But the critical decision about the destination of the pipeline remains unresolved. The new agreement means this is less a bilateral negotiation between Australia and Timor Leste, and more a complex multiparty negotiation between these states and a consortium of oil companies.

For the past decade, Timor-Leste’s politicians, led by former Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, have advocated for Greater Sunrise gas to be piped to the south coast of Timor-Leste for processing. However, the Woodside-led consortium, which holds rights over Greater Sunrise, has indicated that this is not a commercially viable option. The task for Timor-Leste’s negotiators now is to persuade reluctant industry partners to relent on the course of the pipeline.

The Woodside consortium’s primary responsibilities are not to citizens or the broader international community, but to its shareholders. In the past, Woodside has been more than prepared to shelve the project. It is not clear whether the development of Greater Sunrise, which potentially involves the construction of a technically challenging and expensive pipeline across the Timor Trough to Timor-Leste, is an attractive option for development, or whether the timing fits with Timor-Leste’s need for the gas to flow and resulting profits to replenish its dwindling sovereign wealth fund.

Dwindling funds

It is hard to overstate how consequential the timely development of Greater Sunrise is for Timor-Leste’s economy. More than 90% of its national budget comes from oil in fields that will be depleted in less than five years. It has very few sources of non-oil income, and its petroleum fund won’t last ten years on current spending.

This lack of diversity in the Timorese economy has meant that Timor-Leste continues to rely on unlocking Greater Sunrise revenues. As commentators have observed, even if this happens, what the revenue split means in real terms for Timor-Leste is uncertain. If the country receives 80% of the US$40 billion field, the royalties to Timor-Leste are only likely to be approximately US$8.16 billion.

The issue of the boundaries as a matter of sovereignty, while symbolically important, is a distraction from the core consideration. What really matters for Timor-Leste’s sovereignty and its economic viability is a quick resolution on the pipeline, leading to a swift development of the fields. The parties have still not come to an arrangement about how the gas from Greater Sunrise will be processed. A leaked letter from Gusmão, who led the negotiations, has accused Australia of colluding with the oil corporations to prevent the pipeline. This suggests that the Timor Sea dispute is far from over.

The new agreement is the product of an intense negotiation, facilitated by the Conciliation Commission. But negotiating with oil corporations driven by profit is an entirely different proposition. It is to be hoped that the Conciliation Commission’s report, due out mid-April, will offer pathways for the development of Greater Sunrise. However, an overly aggressive negotiating strategy runs the risk of pushing back the development of Greater Sunrise, with disastrous implications for Timor-Leste’s economy, and ultimately its viability as a state.