Over the past year, the US has been engaged in what it calls a maximum pressure campaign to push North Korea to take concrete steps towards denuclearisation. President Donald Trump has imposed a series of sanctions on North Korea, and threatened nuclear war against the country on Twitter.

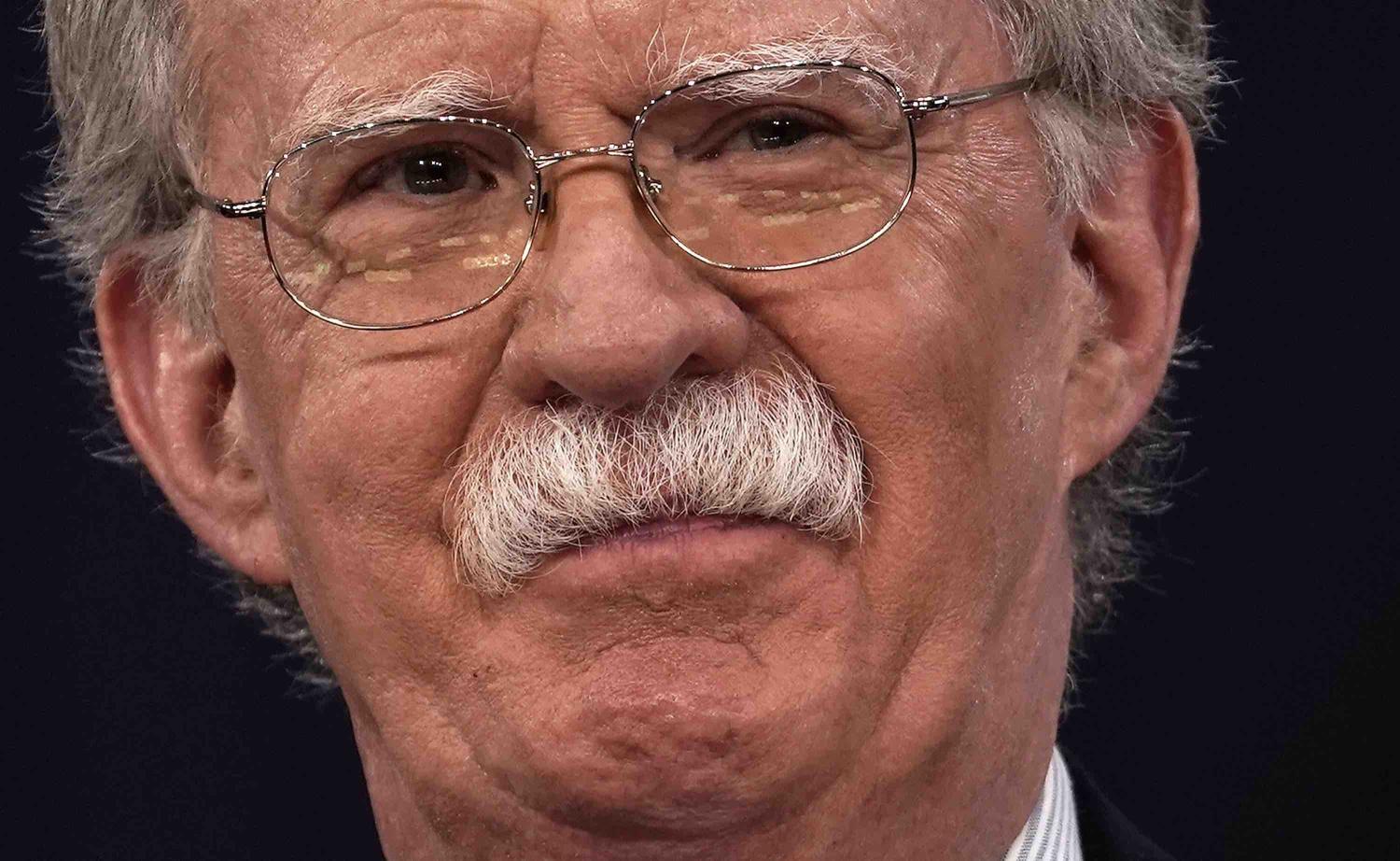

Yet there is scant detail as to how the US will approach the upcoming summit with North Korea. Trump’s new National Security Adviser, John Bolton, perhaps has been the most explicit, stating that if there is a model for how to peacefully rid a hostile dictatorship of its nuclear program, it is found in the past experience with Libya.

In March this year, in a radio interview given just before his appointment, Bolton first alluded to the so-called Libyan model. He said the only thing there was to discuss with North Korea was:

… what ports should American freighters sail into and what air bases should American cargo planes land at so that we can dismantle your nuclear weapons program, put it in those planes and boats and sail it back to America to put it at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

In 2003, as Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Bolton was part of the Bush administration that successfully negotiated a denuclearisation deal with Libya.

Under that deal, documents and equipment related to Libya’s nuclear and ballistic program, as well as chemical weapons ingredients, were shipped to Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Subsequently, sanctions were gradually lifted and relations with Libya ultimately normalised.

In April this year, in his first series of interviews as the new National Security Adviser, Bolton raised the Libya example again, saying:

We have very much in mind the Libya model from 2003, 2004. There are obviously differences. The Libyan program was much smaller, but that was basically the agreement that we made.

The fate of Muammar Gaddafi – overthrown in an uprising and killed nearly seven months into a NATO-led military operation – as well as the recent tearing up of the Iran deal by the US may do little to assure the North Koreans. At the same time, Kim Jong-un’s negotiating hand is much stronger than Gaddafi’s because of North Korea’s existing nuclear inventory, which is far ahead of what Libya possessed in 2003.

The issue, however, is not how North Korea compares to Libya (or Iran for that matter), but what lessons the Libya experience provides for the current US administration.

In December 2003, Gaddafi announced a strategic decision to irreversibly denuclearise. Bolton has said he is looking for an unreserved commitment from North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons, instead of hedging.

But to extract such a commitment from Pyongyang, the US would need to be willing to spell out what North Korea would get in return. At the least, Bolton should be thinking of nuclear disarmament as an overture to sanctions relief, as was the case in Libya.

The North Koreans may well want more in a grand bargain (read: withdrawal of all US forces, and a nuclear guarantee), and the question is how far the US is willing to go (read: not very far).

Libya’s complete “stockpile” was verified by inspectors and taken out of the country on relatively short notice, but this seems unlikely in the case of North Korea. In reality, denuclearisation, whether complete or incomplete, would have to be phased and access-negotiated.

It would likely start with a moratorium on nuclear tests, followed by a freeze on the production of nuclear materials and, ultimately, the rollback of warhead stocks. The incentive structure, however, would be similar to the Libya case, where different milestones in the disarmament process were met with incremental recognition by the Bush administration to reward Libya’s progress.

Kim Jong-un has pledged to close the Punggye-ri facility, where all six of North Korea’s nuclear tests were conducted between 2006 and 2017, in the presence of “foreign experts”, but the US will take this action with the appropriate caution. The latest prevarication from North Korea about holding the summit at all hinged on distaste with the Libya precedent, according to some observers, including North Korean senior diplomat Kim Kye Gwan:

Whiplash alert: North Korea says maybe it will hold that summit with Trump -- but only if Washington stops unilaterally insisting that it gives up its nuclear program and only if they stop harping on about Libya. This comes from Kim Kye Gwan so carries a lot of weight

— Anna Fifield (@annafifield) May 16, 2018

As a whole, the implementation of an agreement struck by the US and North Korea next month will be even harder than concluding one.

Joseph Cirincione, President of Ploughshare Funds, a foundation focusing on nuclear issues, hit the nail on the head when he said:

If Trump thinks that he’s going to come back from the summit with Kim Jong-un’s nuclear weapons in the cargo hold of Air Force One, he’s delusional. If he goes in prepared to have this be a breakthrough meeting that yields important concessions from Kim and is the start of a multi-year process toward denuclearisation, then he might be able to pull off a stunningly successful summit.