Carlos Ghosn’s fall from grace is one of the most amazing recent episodes in international corporate life.

It seems just like yesterday that Carlos Ghosn was the “rock-star executive” who in 1999 restructured and saved the highly indebted Japanese motor vehicle maker Nissan on behalf of Renault, its French Alliance partner.

Ghosn, a polyglot with French, Brazilian, and Lebanese nationalities, broke many of the rules of Japanese corporate life as he cut jobs, plants, and suppliers, and shook up Nissan’s lifetime employment and seniority management system. But nothing succeeds like success, and within 12 months, Ghosn quickly returned Nissan to profitability, and it became one of the industry’s most profitable companies.

There was more than a tinge of sarcasm in the nickname that Ghosn was assigned – “le Cost Killer”. But a multitude of books, including one by Ghosn, on Nissan’s revival were best-sellers. Ghosn even became a hero in Japanese manga comic books.

Widespread public opinion believes that the extraordinary security of Japanese society is a result of its tough judicial system. And in response to any scandal, the usual reaction of corporate Japan is to close ranks.

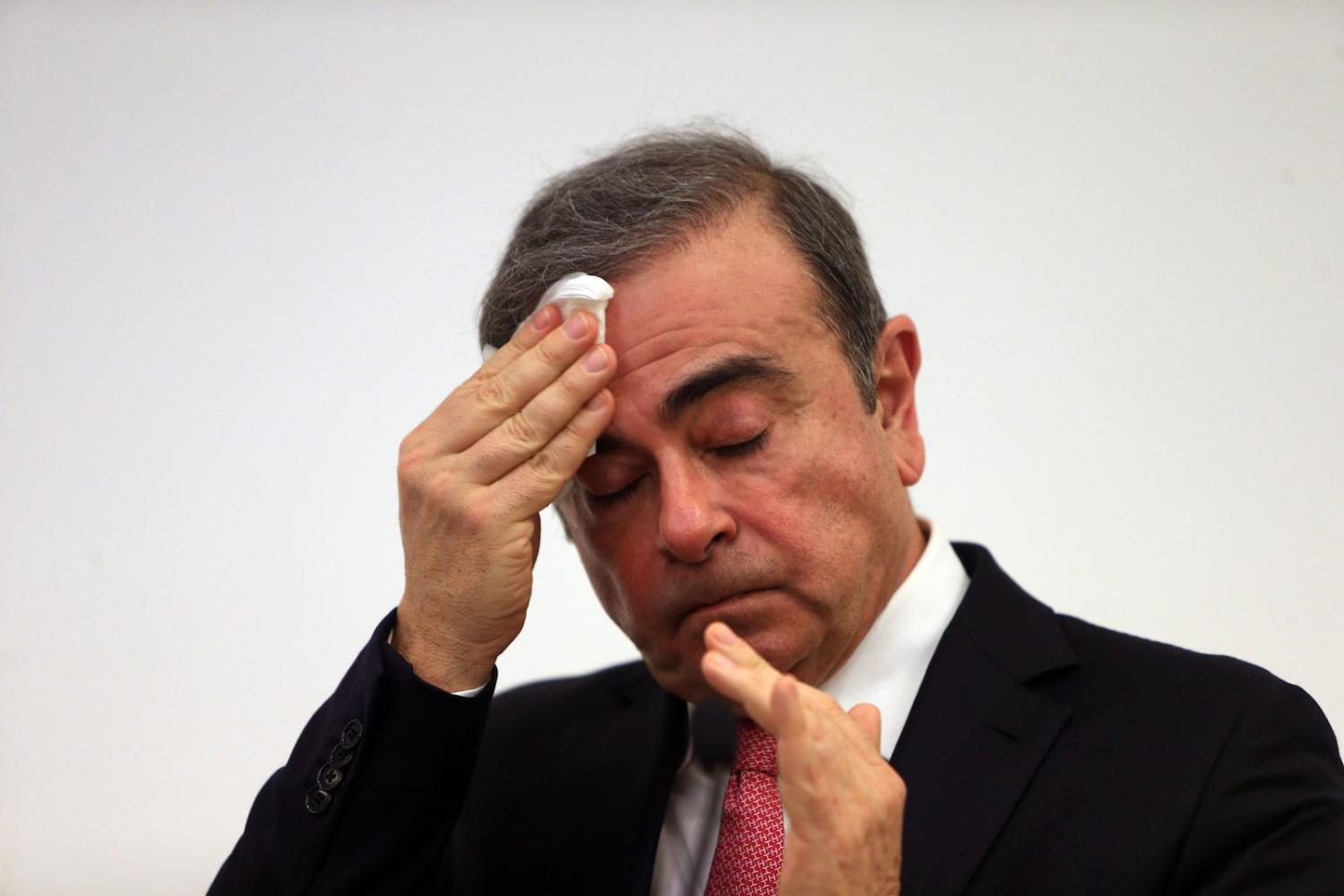

From all reports, Ghosn’s success would change the man. The motor-vehicle magnate in ill-fitting suits who would venture onto the factory floor to rub shoulders with the workers became presidential and aloof, donning designer suits and jetting around the world in private planes.

His insistence on seemingly exorbitant salaries ruffled feathers, especially in Japan, where modesty is a watchword for corporate leaders. And when he hosted a lavish party at the Versailles Chateau, many thought this was a major misjudgment.

But Ghosn’s commitment and ambitions for the Renault-Nissan Alliance seemed unrelenting. In 2016, he expanded his empire when Nissan acquired a controlling stake in the troubled Mitsubishi Motors. And at the time of his arrest, discussions were underway with Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.

Out of the blue, in November 2018, Ghosn was arrested as he was getting off his private jet at Tokyo’s Haneda airport. He was accused of under-reporting his earnings and misuse of company assets.

Ghosn would spend more than 400 days either in jail or under house arrest. Soon to be 66 years old, he came to believe that he would spend years in the Japanese justice system.

So it was that on 29 December 2019, Ghosn escaped from Japan in a Hollywood-esque scenario. According to media reports, he left his Tokyo apartment, joined two men at a nearby hotel, took the Shinkansen (Japan’s bullet train) to Osaka, and stayed at a hotel near the airport.

The two men left the hotel carrying large containers, including an audio equipment box in which Ghosn was hidden. They boarded a private jet for Istanbul, where they were picked up by another jet for Beirut, where Ghosn is living now.

Japan would like to get Ghosn back. But there is no extradition agreement between Japan and Lebanon. Interpol has issued a red notice for his arrest. At the time of writing, it is not clear what happens next.

What are we to make of it?

Carlos Ghosn claims he is innocent. The complexity of the case is suggested by the fact that Nissan and Ghosn settled fraud charges by the US Securities and Exchange Commission related to false financial disclosures that omitted more than $140 million to be paid to Ghosn in retirement.

In Tokyo today, opinions are polarised. Most Japanese think that Ghosn’s escape was outrageous and question the competence of the authorities who were watching over him. In contrast, many in the international community believe that Ghosn’s case highlights shortcomings of the Japanese business world and justice system, at a time when the Abenomics program should be opening up the Japanese economy.

In principle, Japan is trying to attract foreign talent, and there are now a growing number of international business executives in Japan. But Ghosn claims that, as a foreigner, he is a victim of discrimination, that Japanese executives who commit similar acts are not arrested and jailed, such as his CEO successor Hiroto Saikawa.

Indeed, many will tell you that foreign managers are never fully accepted or appreciated, and that Japan doesn’t like American-style superstar CEOs, despite more than 150 years of shared history between the two countries. This is a great tragedy for Japan, with its rapidly ageing population and labour productivity more than 25% below leaders in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Japan needs more foreign talent to revitalise its economy.

Second, despite the promise of Abenomics to open up the economy, Japan seems a closed and protectionist economy when it comes to foreign investment. Indeed, Ghosn believes and it is widely accepted that the real reason for his arrest was resistance by Nissan’s Japanese management to Ghosn’s plan for a closer relationship, or even a merger, between Renault and Nissan.

It is noteworthy that despite Abenomics’ goal of doubling the stock of inward foreign direct investment (FDI), some seven years into Abenomics, Japan’s stock of inward FDI remains stubbornly low at 4% of GDP, one of the lowest in the world.

Third, most observers agree that the Ghosn’s alleged financial misconduct should have been resolved inside the Nissan’s corporate management structure. But Japan has long had weak corporate governance despite many government promises for improvement, including as part of Abenomics. According to a recent report, Japan’s corporate governance is ranked only 7th in Asia, tying with India and behind Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan, and Malaysia.

Fourth, while Japan appears an extremely safe country, if you cross the law, its justice system can be draconian. It is often described as “hostage justice”. Suspects can be detained up to 23 days before indictment. Detainees are subject to brutal interrogation, without a lawyer present, by which the authorities pressure detainees to make a confession of the alleged crime. Japanese prosecutors enjoy a 99% conviction rate.

While Ghosn’s fall from grace highlights many shortcomings in Japan’s corporate world and judicial system, it is unclear whether it will lead to any changes. Widespread public opinion believes that the extraordinary security of Japanese society is a result of its tough judicial system. And in response to any scandal, the usual reaction of corporate Japan is to close ranks.

For its part, Nissan has been suffering again in more recent years, especially since Ghosn’s arrest. Ironically, it may need a new Carlos Ghosn to save it again.