Malaysia’s political upheaval looks likely to drag on for years. A three judge panel has granted former prime minister Najib Razak a last minute stay in a corruption trial, which had been set to begin in the High Court last week.

Rather than the charges and a political changing of the guard bringing closure for Malaysia, the Southeast Asian nation looks set to face years of ongoing turmoil as legal proceedings limp along.

Razak, known in Malaysia simply as Najib, is accused of embezzling hundreds of millions of dollars from the state development fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). In 2016, Najib fired the attorney-general investigating the disappearance of up to $4.5 billion from 1MDB, and the appearance of $681 million in Najib’s personal bank account.

His replacement legal advisor cleared Najib of allegations of graft and bribery, prompting declarations from analysts, and Najib himself, that all suspicion had been “put to rest”.

But it wasn’t the end.

Najib’s government was toppled in May last year. He was arrested and charged shortly thereafter, and his wife, Rosmah Mansor, was charged with money laundering and tax evasion in October. Both Najib and Rosmah have pleaded not guilty.

Rather than the charges and a political changing of the guard bringing closure for Malaysia, the Southeast Asian nation looks set to face years of ongoing turmoil as legal proceedings limp along.

Najib faces up to three trials on money laundering and related charges. His defence team deny their appeals and applications for delays are part of a wider strategy to prolong proceedings.

No new trial date has been set.

Najib had portrayed himself coming to office as a reformer who would do away with corruption and loosen social and political restrictions. But when under scrutiny, Najib turned to the repressive tactics he had pledged to do away with. He invoked the Security Offence (Special Measures) Act, widely considered a repackaging of the draconian Internal Security Act, which was used to imprison up to 120 activists during the 1987 Operation Lalang under then-and-now Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.

Public disapproval was evident in the massive swing against Najib’s ruling Barisan Nasional (National Front) coalition.

Yet civil society activists now say that both state and national governments, formed by former opposition parties, are behaving as though the 1MDB scandal backlash handed them a blanket mandate in every arena. There is worry this could threaten tenuous freedoms, while environmentalists in particular fear shoddy economic development projects will be forced through, potentially decimating the already-stressed natural world.

Malaysia now faces something of a political vacuum.

The country’s multi-party coalitions were largely locked in to the same roles for decades; now the tables have turned, leading observers to worry they are unable to perform their new responsibilities. It’s hard to tell where the greater concern lies: with the government’s inability to shed its opposition mindset and govern, or with the spurned former rulers’ lack of desire to act in opposition.

While the executive may be in flux, the judiciary last week handed a victory to the people.

A five-member Federal Court bench unanimously dismissed defamation claims brought in 2013 against activist Shirley Hue Shieh Lee. As vice-chair of Ban Cyanide Action Group, Hue featured in two news articles about Raub Australian Gold Mine, which operated near her family village in Pahang state.

Citizens had raised concerns about the health and environmental impacts of a new tailings pond and mining technique at an existing mine. The defamation case was dismissed by a previous court of appeal, but RAGM was given leave to challenge on four issues relating to freedom of speech.

As Hue and supporters celebrated the decision, Hue’s lawyer, Gurdial Singh Nijar, said the win showed that Malaysian society was now more liberal and accountable, and citizens were entitled to freedom of speech in defence of the public interest and society as a whole.

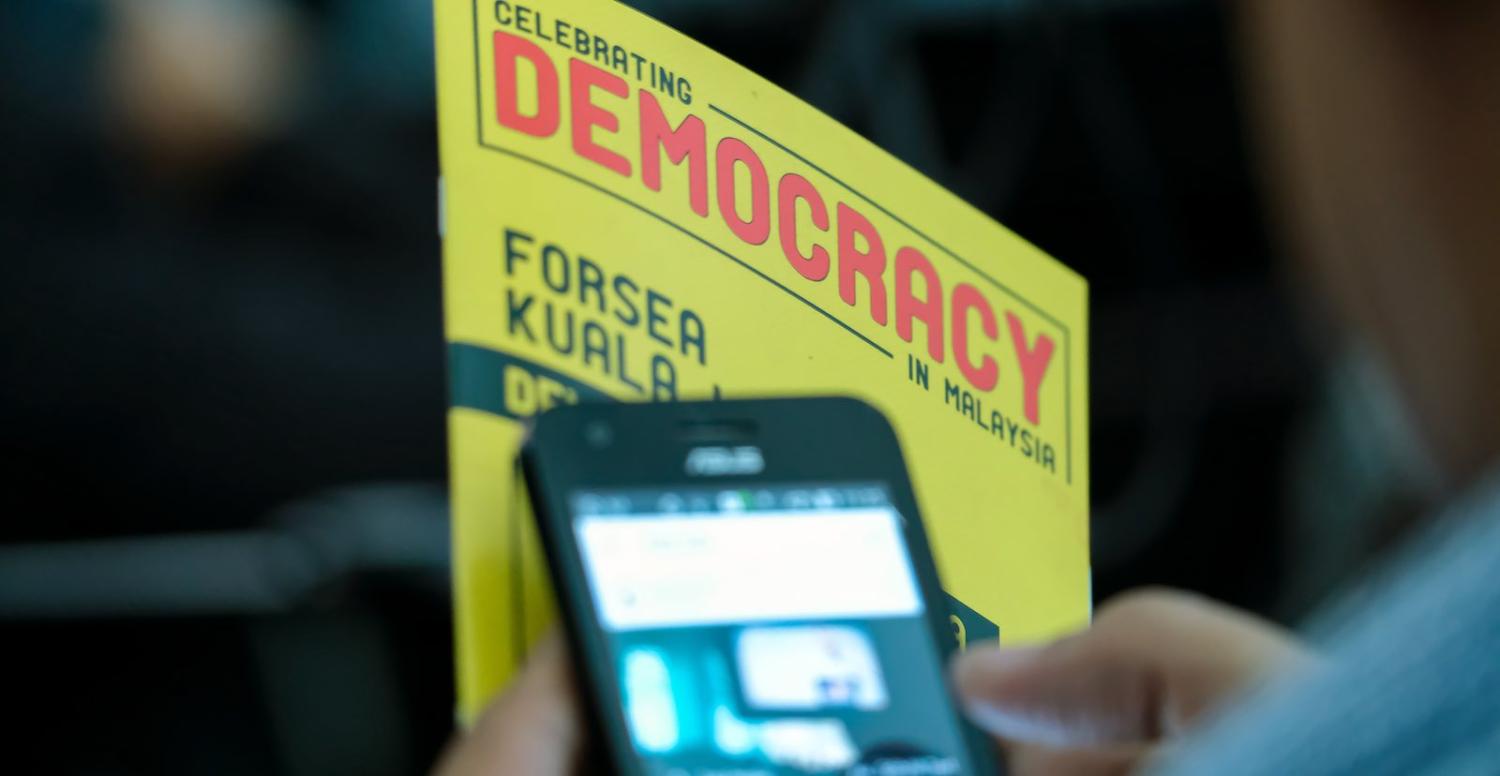

The combination of progress and hesitation came in the same week as the newly-formed pro-democracy network Forces of Renewal Southeast Asia held its inaugural conference in Kuala Lumpur.

The event was helmed by well-known political activist and reformist Hishamuddin Rais, who has variously been jailed without charge (in 2001, under Mahathir), arrested, and fled the country.

Three generations of political exiles and persecuted activists from across the region convened with environment and justice advocates to “celebrate Malaysia’s democratic revival and promote democracy and human rights for all”. The spirit of liberty and energy for the cause were palpable.

The timing of the two-day Democracy Festival was no coincidence; nor was the inclusion of Mahathir and Defence Minister Mohamad Sabu in proceedings. In his opening remarks, Mahathir said that the promises of his Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope) coalition would be difficult to keep, but he conceded that the non-violent overthrow of the former government came with societal demands for change.

The festival, which aimed to consolidate progress and advance the reform agenda, came with a clear message to the political elite: the repression of old will not be tolerated.