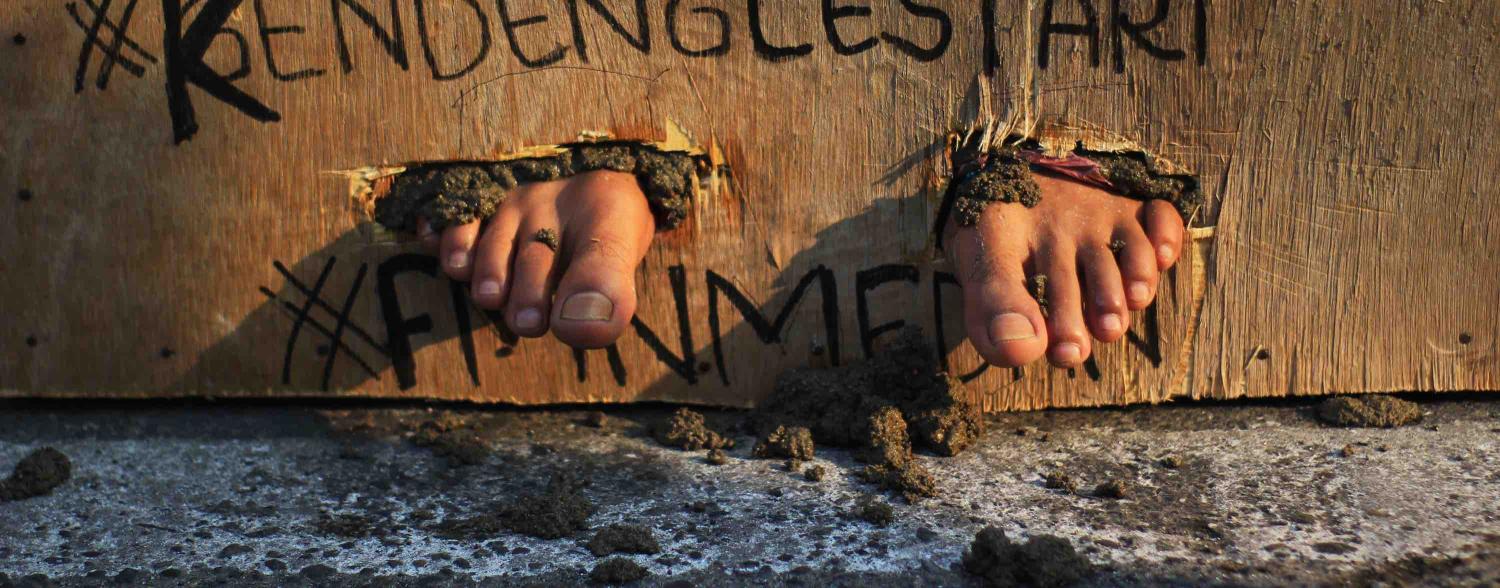

It was an astonishing sight. Nine women dressed in batik sarongs and wearing the traditional, conical hats of Indonesian farmers sat on the edge of the road in front of the Presidential Palace in Jakarta, their feet encased in wooden boxes filled with cement.

This unique protest in March 2017 was held to draw attention to a dispute involving the farmers of Central Java’s Kendeng mountain region, which encompasses the districts of Pati, Rembang, Blora, and Grobogan. Since 2006, the farmers have been fighting cement companies who want to mine the area’s karsts. The farmers (rightly) believe that the mining will pollute their water supply and irrevocably alter the local ecosystem.

As people adhering to the non-violent, agriculture-based “Samin” way of life, working the land is vital to their identity. Through farming, they can not only be self-sufficient but also remain in touch with Ibu Bumi (Mother Earth), ensuring a balance between nature and humankind.

“We all need land, water, and food. We don’t need cement,” says one of the movement’s leaders, Gunarti, in the film Samin vs Semen. “It would be better to have a cement crisis than a food crisis.”

Over the next few days, the protest swelled with about 50 supporters. Every morning and every evening, the farmers feet still in cement, supporters hoisted them onto the back of trucks and wheeled them in and out of the protest site on trolleys. At night, they lay flat on their backs, feet on the floor below them – even going to the toilet required three assistants to move them. The cement blocks were too heavy to walk in.

The protest ended after eight days when one woman, Ibu Patmi, collapsed and died after having the blocks removed.

It has now been more than a year since Ibu Patmi passed away, and still the dispute drags on. Although the farmers have not given up, the issue of Kendeng has been noticeably absent in the lead-up to the election for the next governor of Central Java.

Indonesia will hold its second round of staggered local elections this year, following the first round in 2017. In Central Java, the incumbent Governor, Ganjar Pranowo, is running against the former Natural Resources and Energy Minister, Sudirman Said.

Ganjar is from Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP), the same party as President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, and is a popular anti-corruption figure in the region (although he has recently been accused of receiving bribes in an electronic identity card scandal).

The Indonesian Supreme Court ruled in October 2016 that construction of the cement factory in Rembang must be halted, concluding that it violated Kendeng’s status as a geological area. As Governor, Ganjar refused to accept this decision, and in February 2017 issued a new law that gave the factory permission to continue. Jokowi had previously said he would order the factory to close, but has more recently demurred, saying it is an issue that must be solved locally.

Sudirman is from Gerindra – the party of Jokowi’s likely challenger, Prabowo Subianto.

Much to activists’ dismay, neither Ganjar nor Sudirman have discussed Kendeng in the two election debates held so far. To date, Ganjar has failed to take up the Kendeng farmers’ concerns, even refusing to meet with them after they walked 150 kilometres from their villages to Semarang, the provincial capital. Ganjar and his running mate, Taj Yasin, maintain that the farmers will benefit from the cement factory, reporting they will be offered jobs and shares.

Sudirman and his running mate, Ida Fauziyah, have preferred to stay quiet on the topic, saying they would rather have all of the information at hand before commenting on the factory’s legality. The most adventurous statement Sudirman has been prepared to give came during the second debate, when he said that businesses are the drivers of economies, but that we must talk with them to ensure food security is not threatened.

“We don’t understand why there has been no discussion at all [about Kendeng] in the debates,” Gunarti told CNN Indonesia. “We are waiting to hear what [the candidates] would do to resolve the issue.”

And it’s not only Kendeng’s farmers who are disappointed with the lack of support from candidates in the governor’s race. As many as 120 new mining licenses were released in 2017–18 across Central Java – millions of people will be affected by these new developments, and all are watching the Kendeng issue closely.

It appears that the lure of investment in Central Java is simply too strong for candidates to reject. With more than 5 trillion rupiah (AU$475 million) already invested, the Rembang factory is ready to open once the results of a new environmental impact study are released; that is, if the results favour the factory, which previous studies suggest they should not.

The men and women of Kendeng are prepared to continue fighting for their land, water, and culture; the problem is, their political representatives don’t appear to feel the same way.