The last ten days in Japan have been extraordinary. First, the global Covid-19 pandemic forced the International Olympic Committee to postpone the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics until July 2021. And now, after a slow response, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo has announced a state of emergency for Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka until 6 May 2020. The state of emergency brings powers of enforcement to close theatres and restaurants, and postpone or cancel public events as part of measures to reduce person to person contact. Notably, workers will be encouraged to stay at home, but Abe has stated that a lockdown is not necessary.

The need for stringent measures gained political momentum after the death of the hugely popular comedian Ken Shimura (aged 70) on 30 March. Shimura was the first Japanese celebrity to die of Covid-19 related symptoms and his death shocked many Japanese, many of whom naively assumed the virus was somehow a foreign problem.

It is highly likely that the rate of infection is much higher and that asymptomatic cases have not yet been detected.

The Japanese viewpoint on Coid-19 has also been skewed by the remarkably low rate of infection within the country and the belief that most cases were from the cruise ship Diamond Princess. As of the most recent figures, there are 3,880 cases detected in Japan and 106 people have died, mainly in Tokyo. Notably, only 11 of those who died were former passengers on the Diamond Princess or other cruise ships.

Explanations for the low rate of infection include high levels of hygiene, regular use of masks when suffering from a cold or flu, and a tradition of limited touching (Japanese do not shake hands and rarely hold hands or hug in public). Another important factor is the low level of testing (current rate of testing is one test per 7,600 people) and a policy of focusing on clusters.

It is highly likely that the rate of infection is much higher and that asymptomatic cases have not yet been detected. Indeed, the US Embassy in Tokyo recently encouraged its citizens to return to the United States as soon as possible due to the low rate of testing and inability to access polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. There are now worrying signs that the virus may increase exponentially in Japan. There are already signs of this in Tokyo where, for the first time, over a hundred new cases were detected in a single day.

Abe’s response to Covid-19 has been mixed. He acted decisively to close schools in early March, but has not communicated effectively the importance of social distancing and staying home as preventive measures. On the plus side, on 28 March Abe announced a 56 trillion yen (US$518 billion) economic stimulus package to help reinvigorate the weakening Japanese economy.

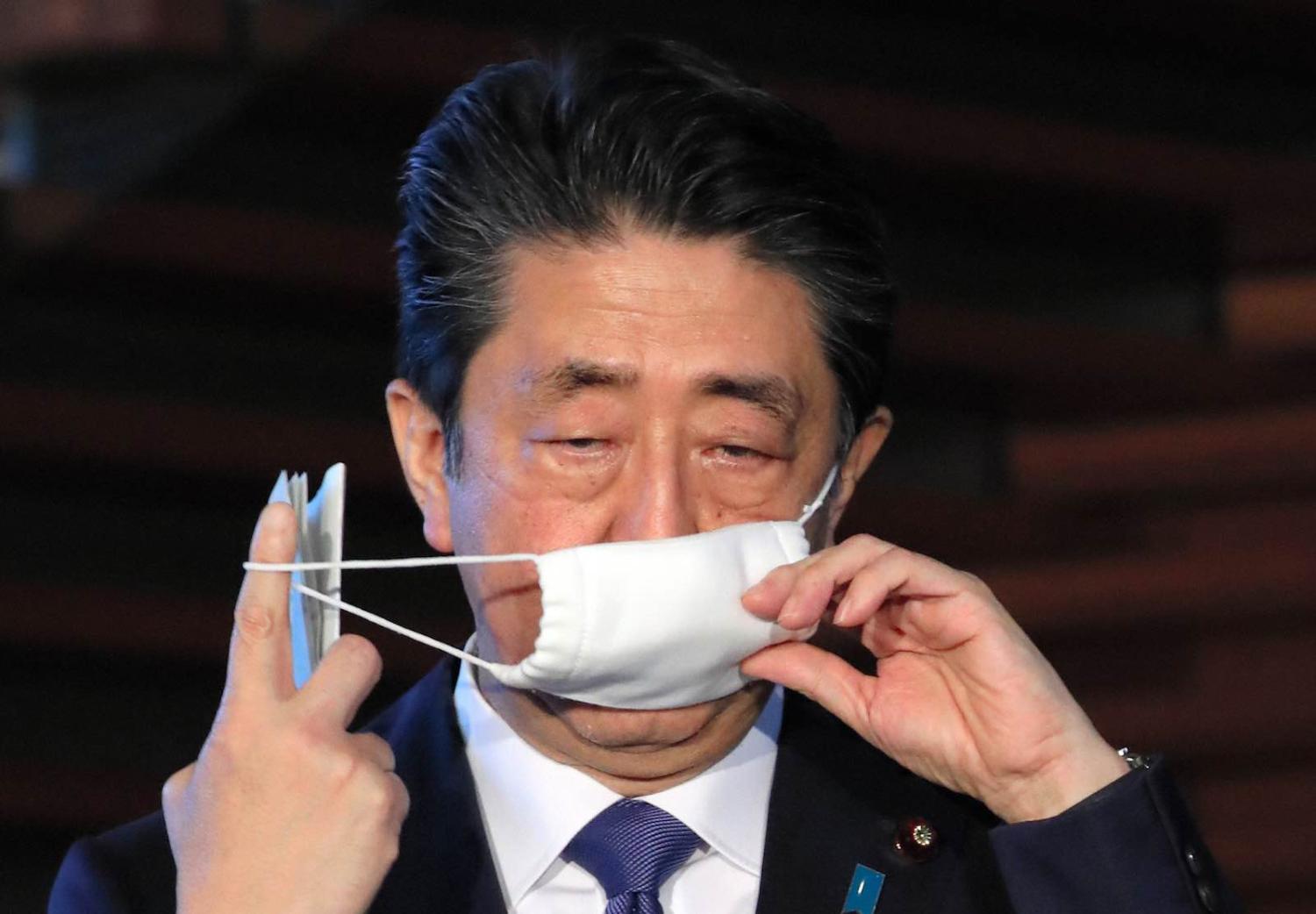

Less straight forward and confusing to many was the decision on 1 April to distribute two reusable cloth masks per household. The initiative was met with ridicule due the 20 billion yen bill linked to the initiative and the lack of financial handouts to support struggling households already equipped with masks. Two days later and perhaps as a result of the derision over supplying masks, Abe announced a one-off payment of 300,000 yen to support households suffering hardship who meet the relevant criteria. The support is estimated to reach just 20% of Japanese households, leaving many households still waiting for support.

Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko on the other hand has offered strong, clear and decisive leadership. Over the past week she has stepped up her public engagements to encourage Tokyoites to avoid a New York type emergency by working from home, avoiding crowded spaces, and practising social distancing. Koike has also called for the hiring and retraining of former medical workers in order to support the city’s medical system. Main department stores and chain stores have followed her lead and are voluntarily closing on the weekends.

Over the past few days Koike has acknowledged that while it is legally difficult to place Tokyo in a complete lockdown, the Japanese government should use their powers to declare a “state of emergency”. Her stance has won strong approval in Tokyo where locals are concerned that Tokyo needs to be prepared before Covid-19 cases spiral out of control.

Perhaps partly as a measure to dilute Koike’s role and high public profile, Abe has taken steps to combat the virus and further support the economy. He now has the emergency law in place and also announced on the same evening an additional 108 trillion yen to help the Japanese economy damaged by Covid-19. Japan has an excellent healthcare system and has the most hospital beds per capita among OECD countries. Nevertheless, with 18.48 million Japanese people aged 75 or over (14.7% of the population) the spread of Covid-19 could have a devastating impact. It is imperative that Abe takes bolder action now to prevent a disaster from unfolding in Japan.

The state of emergency, although welcomed, is late and brings limited powers. A follow-up lockdown or partial lockdown of Tokyo and Osaka and associated tighter controls are required as soon as possible.