On 10 April this year, the 2006 Certain Maritime Agreement on the Timor Sea (CMATS) was terminated. CMATS was an agreement between Australia and Timor-Leste designed to facilitate development of the contested Greater Sunrise gas field, a 5.1 trillion cubic foot gas field in the Timor Sea.

In January, as part of the ongoing UN Compulsory Conciliation (UNCC) maritime dispute resolution proceedings, Timor-Leste notified Australia of its wish to dissolve CMATS. Australia accepted without threatening the terms of the 2002 Timor Sea Treaty. As a quid pro quo, Timor-Leste abandoned two legal proceedings against Australia.

While this move has revived Australia's obligation to negotiate permanent maritime boundaries, it also exposes Timor-Leste to the risk of losing a considerable share of Greater Sunrise. With the CMATS dissolution, agreement on Greater Sunrise now reverts back to the Timor Sea Treaty and a 2003 International Unitisation agreement. According to an Australian Parliament Joint Standing Committee on Treaties (JSCOT) report, this reversion:

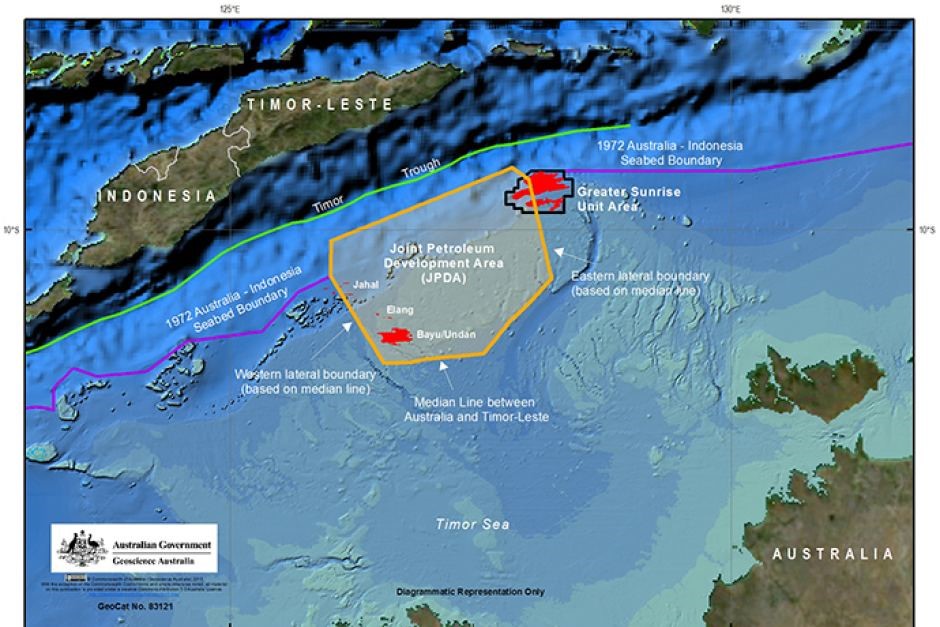

...amends the allocation of Greater Sunrise between Australia and Timor‑Leste. With the termination of CMATS, 80 per cent of the Greater Sunrise unit area falls within Australia's maritime boundary. Of the remaining 20 per cent, Timor‑Leste is apportioned 90 per cent, or 18 per cent of the Greater Sunrise complex in total. This is in contrast to the 50 per cent of the total Greater Sunrise Unit Area Timor‑Leste had negotiated under the CMATS Treaty.

Ownership of Greater Sunrise is contested, and the arguments about who owns it are legally ambiguous, largely due to the fact that the lateral line that splits Greater Sunrise is drawn to simple equidistance (see below). Maritime boundary expert Professor Clive Schofield told the JSCOT hearing that:

We now, potentially, have a long negotiation ahead of us until we can reach an agreement. To achieve anything better than that fifty-fifty split, to put the whole of Greater Sunrise on the Timorese side of the line, is drawing a long bow. It is very difficult to think of the factors in maritime delimitation that would lead to that level of shift in that lateral boundary.

It is impossible to divorce the issue of maritime boundaries from Timor-Leste's economic realities and policies, for three reasons.

First, Dili's economic ambitions have driven its policy approach to the Timor Sea, culminating in the CMATS dissolution. Successive Timorese governments have viewed Timor Sea oil and gas reserves as providing the basis for developing local petrochemical refining industries. Dili's Timor Sea policy has been driven by its need to secure permanent maritime boundaries (and ostensibly 'complete sovereignty'), to take possession of Sunrise, and to establish an export pipeline for the purposes of building a petroleum processing industry on the south coast.

Since 2012, Timor-Leste has reactivated its pursuit of maritime boundaries after failing to secure a pipeline. But rather than abandon industrialisation plans in the absence of an agreement with Australia, Timor-Leste's leaders have continued to develop an oil mega-project, Tasi Mane, which has been promoted as one of the Timorese government's highest priorities.

The likelihood of Timor-Leste gaining all or most of Sunrise is slim, so it is unlikely to get a deal unless it compromises on some of its goals. The question, then, is what goals will be sacrificed. Recent reporting casts doubt on how wedded Timor-Leste's leaders are to Tasi Mane, though this report was subsequently denied.

Second, Timor-Leste's capacity to ensure it remains an independent, sovereign, economically viable state relies on its Timor Sea policy. Timor-Leste's formal economy is currently almost entirely dependent on petroleum exports. Timor Sea oil revenues have been crucial for Timor-Leste's independence and economic viability (furnishing 90-95% of state budgets), and enabled Timor-Leste to build a Petroleum Wealth Fund worth US$16 billion. The oil in the JPDA will run dry around 2020-2022. Projections by independent economic monitor La'o Hamutuk suggest that on current spending the wealth fund will last until 2026-2028.

Timor-Leste's capacity to be self-determining depends in part on its economic viability. Heavy loan or aid dependency in the future would compromise its decision-making autonomy. Ensuring future economic viability, and sharing oil and gas wealth across the community in ways that promote political order and human development, is central to securing Timor-Leste's hard fought sovereignty. This will depend on the timely resolution of the Greater Sunrise dispute.

Third, since 2012 Timor-Leste has employed an 'activist' foreign policy strategy characterised by a concerted public relations campaign designed to change Australia's Timor Sea policies through grassroots public pressure. Yet Australia's Timor Sea history provides little basis for optimism for a policy shift from Canberra. While public diplomacy has influenced public narratives in Australia, it has not been enough to shift Canberra into a position inimical to its key interests. Crucially, despite the Timor Sea being cast as a bilateral issue, it is actually a trilateral one, with Indonesia also involved. And Australia's first-order foreign policy priority is not Dili but Jakarta.

It is in the interests of both Australia and Timor-Leste to find a compromise in their negotiations, yet this need is undeniably more intense and urgent for Timor-Leste. Severe oil dependency exacerbates Dili's negotiating vulnerabilities with Australia. Without an agreement, Timor-Leste will be left with very few sources of revenue outside its $16 billion petroleum sovereign wealth fund. An eventual return to aid dependence would undermine political independence and Dili's capacity to advance development goals.