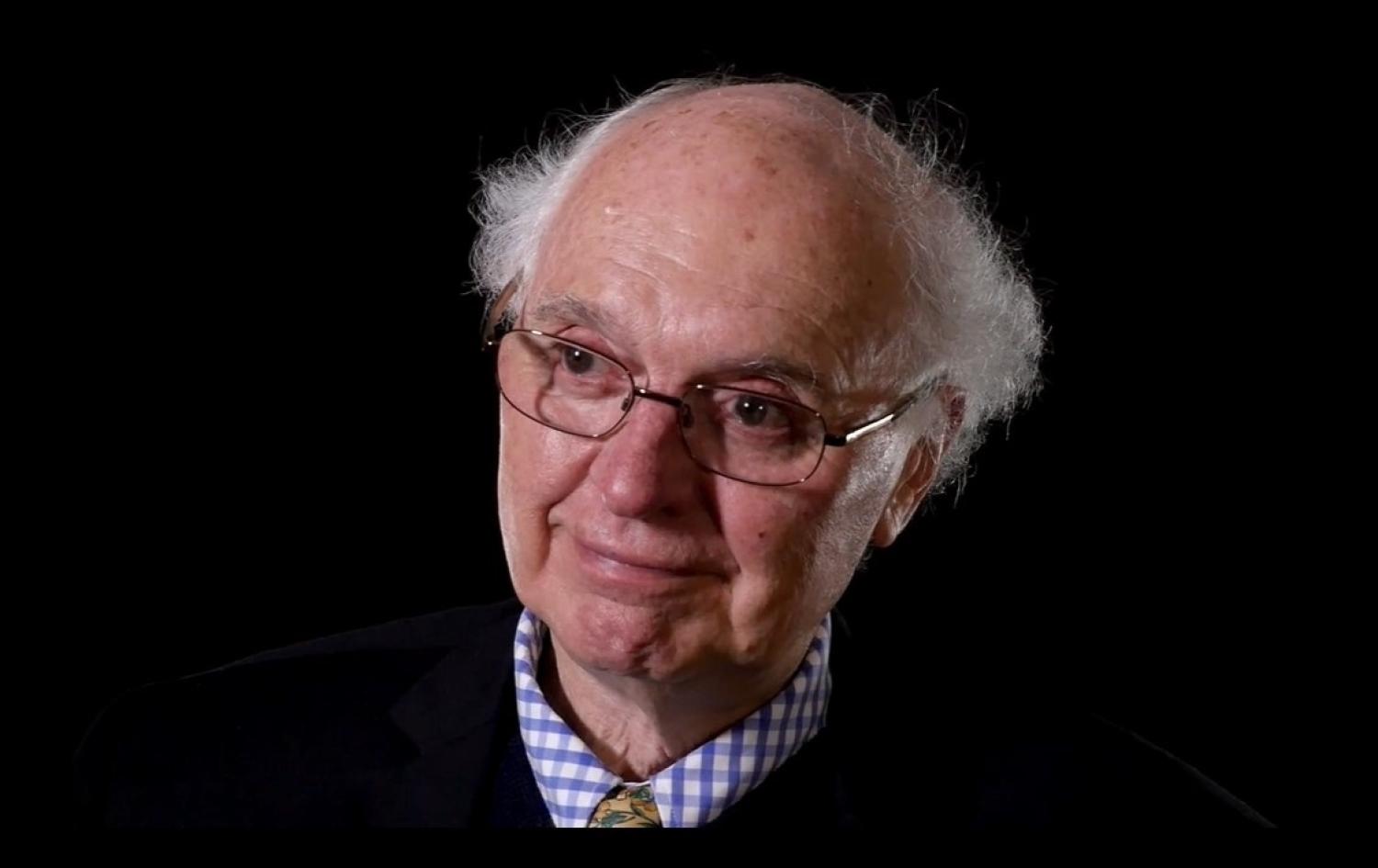

Robert O’Neill, who died last week, was a towering figure in three fields, summarised in the title of the 2016 festschrift in his honour: War, Strategy and History. These three fields – the conduct of military operations, especially counter-insurgency; national, regional and global strategic studies; and military history, especially its diplomatic and strategic aspects – were intertwined throughout his stellar career and well into his retirement.

As a young officer in one of the first Australian battalions in Vietnam, O’Neill led the development of a distinctive style of counter-insurgency operations, focusing on winning hearts and minds rather than kill ratios and body counts. His letters to his wife Sally were later collated and edited into the book Vietnam Task. Like Vietnam Vanguard, the book he co-edited decades later based on accounts of his colleagues in the battalion, it remains a valuable resource on Australia’s Vietnam War. This was also the start of a lifelong contribution to the study of insurgency and counter-insurgency, a topic on which many American military thinkers valued his advice and support.

As shown by his appointments as Director, and later Chairman, of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), until then a predominantly transatlantic body, O’Neill was one of the few Australians who were regarded globally as leading authorities in the new, and often controversial, field of strategic studies. Earlier, having left the Australian Army to enter academic life in the 1960s, he had been appointed Director of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre (SDSC) at the Australian National University, where his credibility in academic, military and policymaking circles and his diplomatic and fundraising skills helped to establish the Centre as Australia’s first significant think tank in the field.

Even while holding senior positions in strategic studies, military history remained his first love. O’Neill’s first book, on relations between the Nazi Party and German Army in the 1930s, based on the doctoral thesis he had written as a Rhodes Scholar in Oxford, was published while he was serving in Vietnam. His German was good enough not only to read documents but to interview retired German generals and even establish a rapport with one or two. The book remains a classic in the field.

While heading the SDSC, he was appointed Australia’s official historian of the Korean War, where his major contribution was to see that the diplomatic and strategic aspects of Australia’s involvement (including the negotiation of the ANZUS Treaty) were more significant than the strictly military. His two volumes not only constituted a history of lasting value but also marked a crucially important development in the tradition of Australian official war histories. Its continuing relevance is demonstrated by the recent publication of Craig Stockings’ volume on the East Timor commitment.

O’Neill’s thesis on Nazi Party–Wehrmacht relations in the 1930s was supervised by Norman Gibbs and examined by Michael Howard. In the 1980s, O’Neill succeeded Howard, who in turn had succeeded Gibbs, as Chichele Professor of the History of War at Oxford, perhaps the most distinguished academic position in the field. Like Howard, O’Neill kept contact with leaders in military and strategic affairs, constantly fostering discussion on the relevance of the recent and distant past to the present and possible futures.

During his time at Oxford, O’Neill had a profound and enduring influence through his lectures and seminars and, perhaps most notably, as supervisor of more than 50 doctoral theses. Many of his students went on to senior academic, military or government positions and remained in close contact with O’Neill long afterwards.

O’Neill was a strong supporter of many institutions in his fields of interest, whether established and venerable or new and vulnerable. While in the United Kingdom, in addition to his time as Chairman of the Council of the IISS, he also served as Chairman of the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum; Chairman of the Council of the Centre for Defence Studies at King’s College London; Chairman of the Sir Robert Menzies Centre for Australian Studies at the University of London; a member of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission; a Governor of the Ditchley Foundation; and a Rhodes Trustee. He was still in London when Prime Minister Paul Keating and Foreign Minister Gareth Evans appointed him as a member of the Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons, joining a highly distinguished body of global political and military leaders.

Michael Howard’s description of O’Neill as “a chairman made in heaven”, with the “air of easy authority that immediately inspires confidence and marks him out as the obvious person to take charge of any enterprise to which he has set his hand”, was as evident in Australia as it was in the United Kingdom and the international circles in which he moved. When he returned to Australia in 2001, supposedly in retirement, he played a major role in the establishment of three new think tanks – the Lowy Institute, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (as foundation chairman) and the United States Studies Centre.

While making a huge contribution in the study of war, strategy and history, O’Neill earned the confidence, trust and admiration of all who worked with him, from senior policymakers to nervous postgraduate students. In that, as in every other aspect of his extraordinary life and career, he had constant and strong support from Sally.