Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to its near-complete political and economic estrangement from the West. This has obliged Moscow to intensify reorientation of its foreign policy, a shift outlined in the publication last month of its new Foreign Policy Concept.

The document portrays the United States and its Western partners as pursuing a “new type of hybrid war … aimed at weakening Russia in every possible way”. As a consequence, Russia is seeking to expand “constructive” relations elsewhere, taking advantage of the more fluid, multipolar global situation.

In short, Russia doesn’t expect early improvement in its relations with the West, so it’s actively courting new partners, to avoid political and economic isolation.

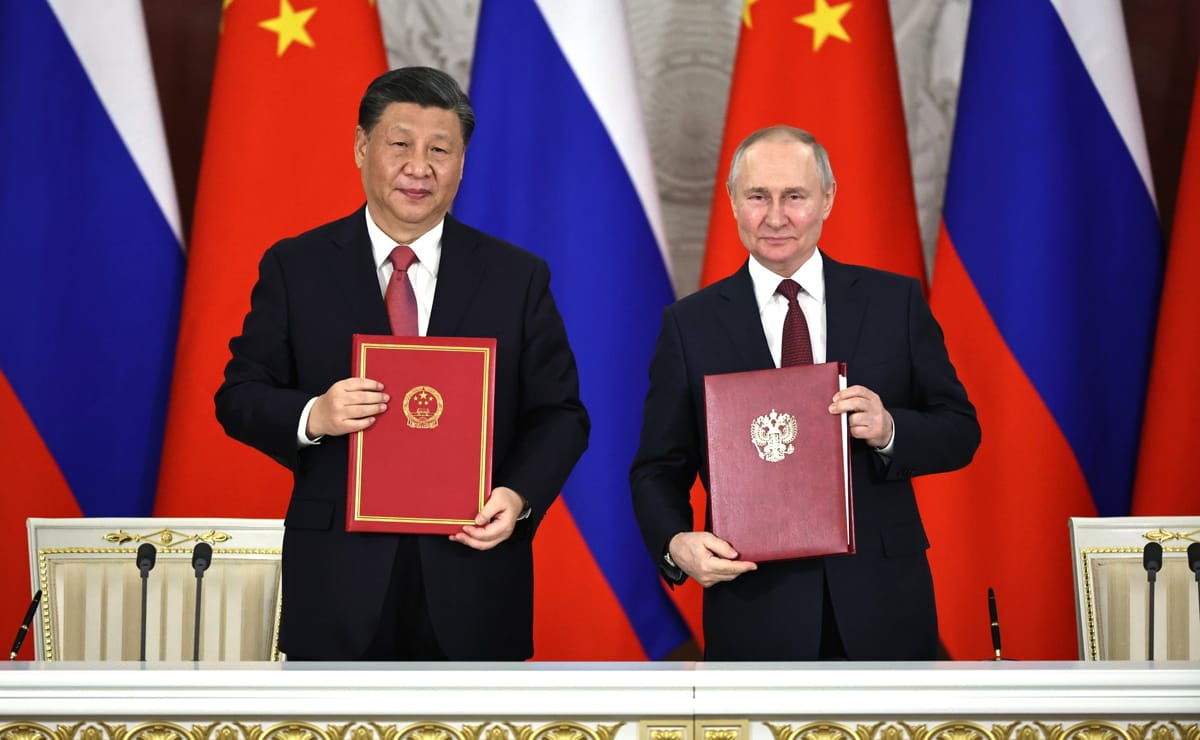

Above all, Russia has drawn closer to China, forging a “comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation”. Russia and China are logical partners, sharing political affinities, economic complementarity and broad foreign policy convergences.

But Russia’s falling-out with the West has also made closer relations with Beijing a strategic imperative. Moscow needs Beijing’s political backing, not least in multilateral forums, while China provides an alternative market for Russian hydrocarbons and commodities, as well as a source of critical manufactures.

For Beijing, Moscow is a like-minded partner, sharing a strategic outlook centred on antipathy to US primacy, a wish to recast the international order to better reflect their interests, and resentment at perceived “encirclement” by America and its allies.

Yet it is an increasingly unequal relationship, in which Beijing is the dominant partner. Moscow knows, and probably resents, this – but it has no choice.

China supports Russia politically over Ukraine. And it has thrown Moscow an economic lifeline. But whether China will be jeopardising its wider interests (including with the West) by providing military assistance for Russia is moot.

China needs Russia to survive but not necessarily thrive as a compatible yet subservient partner.

Beijing doesn’t want to see Moscow defeated in Ukraine. But Beijing may not be dismayed at on-going war in Ukraine because this distracts US and European attention and resources away from the Indo-Pacific, while increasing China’s leverage over Russia, notably access to discounted oil and gas.

Russia enjoys a “privileged strategic partnership” with India. The relationship has strong historical roots, dating back to non-aligned India’s shared anti-colonial sentiment with the Soviet Union. India has carefully avoided taking sides in the Russia-Ukraine war.

Russia has long been New Delhi’s main arms supplier. While India’s weapons sources are becoming more diverse, it still needs Russian logistical support to maintain its existing weapons inventory.

India is a major oil importer, and rapid economic growth is driving increased demand. In the past year, India has massively increased purchases of cheap Russian oil.

India values close, stable relations with Russia as a strategic hedge against China, its main rival. The more so now, as India views warily Moscow’s closer relationship with Beijing, prompting New Delhi in turn to boost ties with the United States, Japan and Australia.

Russia’s relations with Türkiye are complex yet pragmatic.

Ankara needs good relations with Moscow to achieve strategic autonomy, balancing key great power relationships, and leveraging Türkiye’s weight and strategic location to exercise regional power and influence. But their ambitions can produce friction points: Russia and Türkiye backed opposing sides in Syria, Libya and the South Caucasus, while they are rivals in Central Asia.

Trade between Russia and Türkiye has grown sharply over the past year. More Russian tourists and hydrocarbon imports have bolstered the languishing Turkish economy, while easing sanctions pressure on Russia.

Despite strains, the two countries have managed their relationship effectively, cooperating where they can and working around each other where they can’t.

As with Türkiye, Russia’s centuries-long relationship with Iran has been complicated, often acrimonious. For now, their shared pariah status with the West has thrown them together – but it’s not a trusting relationship.

For Russia, Iran is now a key source of military equipment, especially drones, to support its war in Ukraine. And Moscow can probably learn from Tehran’s long experience at navigating Western sanctions.

Meanwhile, Iran seeks Russian technology, including modern fighter planes and air defence systems. Moscow can also provide helpful political cover for Tehran, especially in the UN Security Council.

Yet their relationship will remain wary. Russia wouldn’t, for example, relish its near-neighbour acquiring a fully-fledged nuclear weapons capability. And Russia must balance other important relationships in the region, notably Israel.

Russia’s relations with Saudi Arabia, hostile during Soviet times, have improved markedly. This was symbolised by King Salman’s 2017 visit to Moscow, but has intensified under Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s de facto leadership.

But Moscow’s relationship with Riyadh is essentially one of convenience, based on their shared interest in managing the world oil market. Between them, the two states account for about a quarter of global oil output, and they cooperate closely as part of OPEC-plus.

Moscow’s not just wooing large and middle powers. Russia has also successfully expanded ties with the Global South, notably in Africa, promoting its political and economic interests. It exploits growing disaffection with Western states, and disillusion that the existing international order hasn’t delivered enough for developing states, including debt relief, pandemic assistance and climate change.

What’s the common thread running through Russia’s bilateral diplomacy? It’s Moscow’s focus on interest-based relationships, often narrowly defined. Iran and Saudi Arabia are good examples.

Moscow compartmentalises bilateral relationships in an entirely pragmatic and transactional way – cooperating where it is mutually advantageous, but otherwise skirting round differences. Values (even as defined disingenuously in the Concept from the Russian perspective) don’t in practice figure in Moscow’s foreign policy calculations and statecraft: it’s a hard-nosed realist approach.

And so far, it’s working.